('Woman's Silhouette' © Chris Goldberg, 2011)

HAPPY AFRICAN FEMINIST

by ANDISWA ONKE MAQUTU

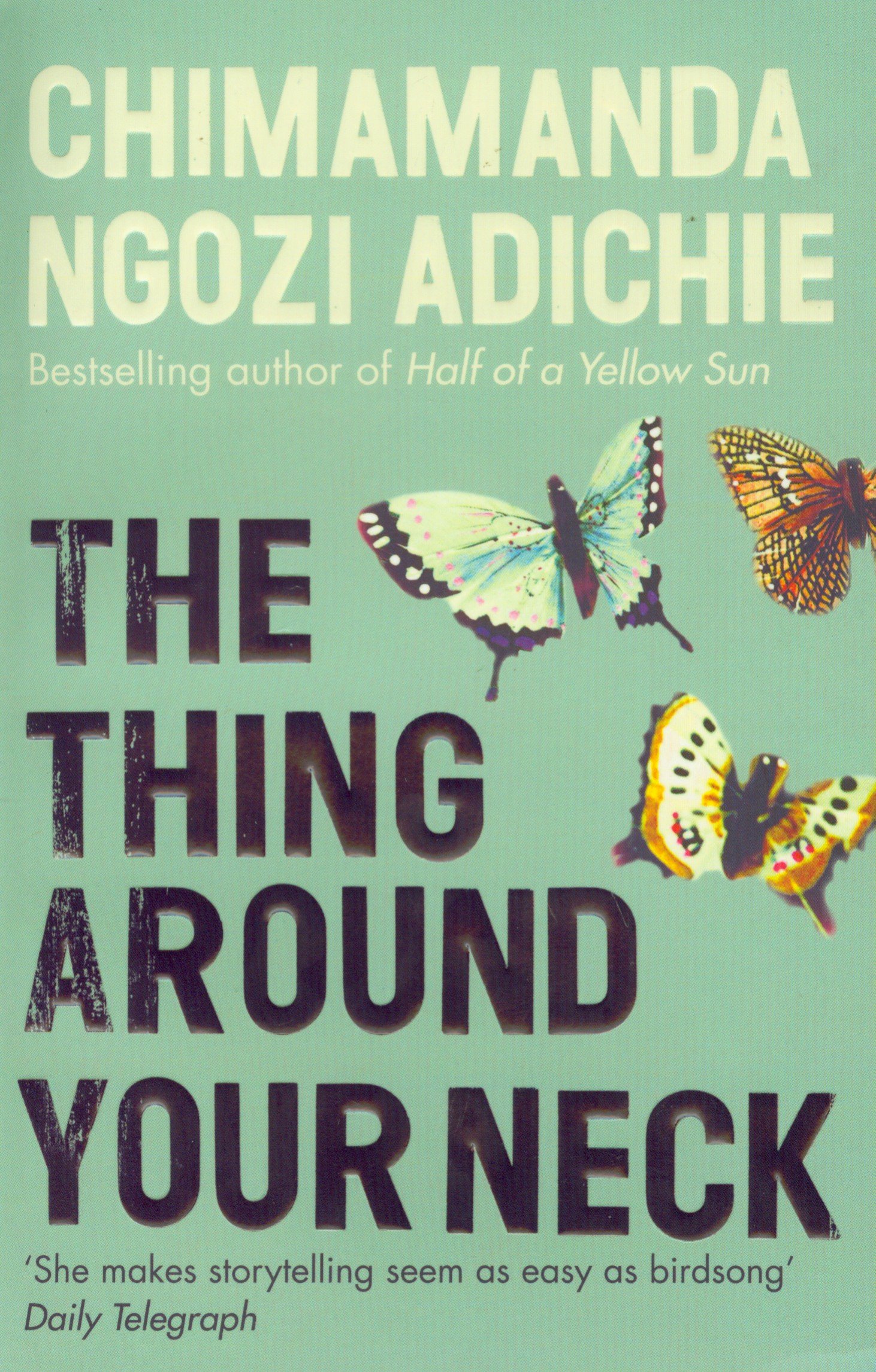

African. Black. Feminist. Unapologetically Nigerian. Arrogant – of the kind admired and hated in Nigerians by some from other African states. This is how Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie writes her collection of stories, The Thing Around Your Neck.

The stories are centred in Nigeria but travel in, around and between Nigeria and the United States of America. It is a collection exploring migration: its freedoms, the way it opens new worlds, new ways of seeing an old and familiar world, the protection of the new world, and also the limits it places on Africans.

It is about that feeling of not quite belonging, that feeling that the new thoughts are not quite the characters’ own, and it is about the judgement to which the characters would be subjected were their thoughts revealed at home. Part of the migration of the mind takes place through music and movies, so that a Nigerian can become American, though he has never been and may never be – to the extent that the reader wonders if America is ‘The Thing Around Your Neck’ that Adichie refers to in her title.

It is also a collection about black Nigerian women; a feminist perspective telling each short story, just as they do in Adichie’s novels.

The book is a mosaic of Adichie’s own life. She was born in the university town of Enugu, Nigeria, to a professor of statistics at the University of Nigeria and his wife, the institution’s first female registrar. A number of the stories in the anthology explore university life and the lives of academics and their children. Adichie is able to accurately present that tug-of-war experienced by the elusive African black middle-class, new to money, travelling between and reconciling wealthy and poor backgrounds, and trying to instil and preserve Nigerian principles in Westernised children.

Adichie – true to herself as a self-proclaimed ‘Happy African Feminist Who Does Not Hate Men’, possibly inspired by her mother’s achievements and what that meant for a young black girl growing up in patriarchal Nigeria and Africa – presents all her characters as somewhat feminist. Feminist in the sense of owning their decisions, and through that loose agency, trying to influence the decisions of others around them.

The narrator of the first story in the collection, ‘Cell One’, is a young, precocious and perceptive girl whose name we never learn. In fact, she does not speak directly at all in the story, except once, and only to ask her father – in one word – ‘Why?’ he thinks he should have punished her brother differently when the boy robbed his own parents. In contrast, the narrator’s mother, her father and her brother, Nnamabia, have voices. The father and brother’s being the strongest and most prominent, changing the events in the story.

Though told through the eyes of this curious young girl, the tale revolves around her troubled brother – a charming and eager-to-prove-himself teenager – exploring the dizzy way that mothers often smother and discipline their favourite sons.

Though told through the eyes of this curious young girl, the tale revolves around her troubled brother – a charming and eager-to-prove-himself teenager – exploring the dizzy way that mothers often smother and discipline their favourite sons.

It is the lack of a voice for the young girl that gives the reader insight into the importance placed on boys in African homes. Through this narrator, Adichie shows how the criminal behaviour of a boy, however petty, can shadow the intelligence a girl might show at home. Because her brother is a boy, and she a girl, she is silenced to the extent that she expresses herself quite neurotically and, uncharacteristically, immaturely. The reader is forced to remember that she is young in light of the war she fights against patriarchy.

When her brother is arrested for his gang involvement and moved to a prison in another state, it is the young girl who sees the financial and emotional drain of visiting him every day. However, even with that incisive and mature observation, her lack of a voice leads her to express herself in childish and erratic ways:

The second week, I told my parents we were not going to visit Nnamabia. We did not know how long we would have to keep doing this and petrol was too expensive to drive three hours every day and it would not hurt Nnamabia to fend for himself for a day.

My father looked at me, surprised, and asked, “What do you mean?” My mother eyed me up and down and headed for the door and said nobody was begging me to come; I could sit there and do nothing while my innocent brother suffered. She was walking toward the car and I ran after her, and when I got outside I was not sure what to do, so I picked up a stone near the ixora bush and hurled it at the windshield of the Volvo. The windshield cracked. I heard the brittle sound and saw the tiny lines spreading like rays on the glass before I turned and dashed upstairs and locked myself in my room to protect myself from my mother’s fury. I heard her shouting. I heard my father’s voice. Finally there was silence, and I did not hear the car start. Nobody went to see Nnamabia that day. It surprised me, this little victory.

In line with the theme of America, Nnamabia – ever the extrovert and as beautiful in looks as his mother – gets mixed up in a cult of middle-class boys, who grew up ‘…watching Sesame Street, reading Enid Blyton, eating cornflakes for breakfast and attending the university staff primary school in smartly polished brown sandals’, but who are now involved in petty gang violence gone deadly. Adichie describes this behaviour of boys raised on silver spoons with nothing to fight for, now killing each other at every aggravation, as ‘eighteen-year-olds who had mastered the swagger of American rap videos’.

Eventually the narrator’s brother is arrested for the murder of three boys, along with his friends, who are all cult members. He is innocent, and ruminates about an innocent old man who has also been arrested and is ill-treated by the police. For the first time we see the narrator on her brother’s side.

Although a short story, it is a coming of age tale for both siblings. The little sister is able to see through her brother’s shenanigans with the quiet critical analysis exhibited by her father, but still expresses this with the explosive nature revealed in her mother. And the brother undergoes a sharp learning curve toward mature thinking and manhood, through the experience of being in jail, although it is a sad journey and we are not certain that it is rehabilitative.

The story reveals the intimate and confusing nature of sibling rivalry often nurtured and bred in children by parents like the narrator’s mother, who protects her son, teaching him to take no responsibility. But, somehow, only a few thousand words later, Adichie manages to also speak to patriarchy, American gangsterism and the hostile nature of police towards black men (both in Nigeria and America), failings of the government system, the corruption that middle-class ‘good’ citizens find themselves having to engage in to survive, as well as the tenacity of a young girl in this system that would rather she were silent and, at times, dead.

However, particularly when writing in the context of Nigeria, Adichie is careful not to use the ‘oppressed girl or woman fighting against the injustices in her home’ as a feminist trope.

Adichie’s essay ‘We Should All Be Feminists’ explores the experience of being a black woman in Nigeria, in a world where men have been taught that everything that comes from a woman, ultimately comes from a man, where there are certain clubs and bars a woman will not be allowed into, unless she is with a man. Also, in this essay, Adichie discusses sexuality:

We teach girls that they cannot be sexual beings in the way boys are […] We police girls. We praise them for virginity but we don’t praise boys for virginity […] We teach girls shame. Close your legs. Cover yourself […] And so girls grow up to be women who cannot say they have desire.

Sexuality is a theme she also quietly and tenderly explores in her story ‘Imitation’. Adichie takes us on a journey with a young woman, Nkem – recently wed, living in America with her three children – who sees her husband, one of the fifty most influential Nigerian men, for only two months of a year.

At first glance, Nkem seems to be a timid and submissive wife, only glad for the luxuries her husband provides, but she is also a woman who has desires, material, emotional and sexual. The story is true to the short form, in the way that it takes us through the few hours before Nkem picks up her husband from the airport for his two-month visit. She has just found out, in a phone conversation with a friend, that he is cheating on her with a young girl with short hair, back in Lagos, thousands of miles away.

At first glance, Nkem seems to be a timid and submissive wife, only glad for the luxuries her husband provides, but she is also a woman who has desires, material, emotional and sexual. The story is true to the short form, in the way that it takes us through the few hours before Nkem picks up her husband from the airport for his two-month visit. She has just found out, in a phone conversation with a friend, that he is cheating on her with a young girl with short hair, back in Lagos, thousands of miles away.

In the few hours with Nkem, the reader learns along with her how to express some of these desires – of the self and of a partner – and the sexuality she has explored. Nkem has been loyal to her husband in their marriage, but she has a sexual history that would, as Adichie shows in her essay on feminism, have her viewed as a woman not worthy of marriage in a world where a woman’s chastity is prized and seen as the holy grail. Adichie also skilfully weaves in the issues of class in this story.

She dated married men before Obiora – what single girl in Lagos hadn’t. Ikenna, a businessman, had paid her father’s hospital bills after the hernia surgery. Tunji, a retired army general, had fixed the roof of her parents’ home and bought them the first real sofas they had ever owned. She would have considered being his fourth wife – he was a Muslim and could have proposed – so that he would help her with her younger siblings’ education. She was the ada, after all, and it shamed her, even more than it frustrated her, that she could not do any of the things expected of the First Daughter […] But Tunji did not propose. There were other men after him, men who praised her baby skin, men who gave her fleeting handouts, men who never proposed because she had gone to secretarial school, not a university. Because despite her perfect face, she still mixed up her English tenses; because she was still, essentially, a Bush Girl.

We begin to see the defiance that the protagonist may have, through her ownership of her decisions, as a woman who would be labelled ‘unmarriable’ in Nigeria because of the number of men, some married, that she has slept with. However, at the end of the story her power, its limits and accomplishments, are not revealed: we are left not knowing what Adichie means when she says Nkem knew that her request that her husband move back to Nigeria was ‘done’. In this way, Adichie is showing us again that side of patriarchy, where the woman’s power is defined in terms of what her husband allows her, not what she decides.

In this story, Adichie also reveals how hair can launch a defiance campaign. Nkem cuts her long, flowing, blow-out hair short and uses texturiser to imitate the young mistress her husband has allowed into their Nigerian home. We are not sure whether it is a defiance against her husband’s ideas that ‘,Long hair is more graceful on a big man’s wife’; whether she is imitating the young mistress to appear younger because, as her friend said over the phone, “I hear young people like texturizers now”; or whether it is to let her husband know that she knows of his short-haired mistress. Despite her own protestations in her books and interviews, she reveals that for black women hair is in fact political, romantic, prescriptive, defiant and expressive.

In interviews, Adichie holds her own ground, her accent still richly Nigerian, despite the many years she has lived in America, and she speaks confidently on issues of race, class and feminism. The stories in The Thing Around Your Neck, reflect this side of her, as she handles – with care – women who are in charge of their decision making, even in difficult, power-stripping situations. She shows those who have that defiance and arrogance that Nigerians are able to express, and those who prefer to do their fighting in quieter ways, all seeking a resolution for themselves, rather than a revolution against an entire system.

She explores issues of colourism, and the ideas, shared by many Nigerians – a country that has the largest market for skin-bleaching creams on the continent – that light-skinned women are more beautiful. There are strong explorations of migration, the opportunities of being in a new first-world country away from the limits of Nigeria, and also the limits of the new world. But what stands out most, for me, is that throughout the collection, Adichie forces the reader to ask many questions of themselves, about issues that she has planted through clever and perceptive writing.

~

Andiswa Maqutu is a writer and freelance journalist from South Africa. Her creative writing has appeared in ELLE Magazine, Feminine Inquiry, Kikwetu Journal, Vagabond City and the Killens Review of Arts and Letters of the Centre for Black Studies at the City University of New York. She is also founder of Black Women Be Like, a Pan-African womanist podcast.

Andiswa Maqutu is a writer and freelance journalist from South Africa. Her creative writing has appeared in ELLE Magazine, Feminine Inquiry, Kikwetu Journal, Vagabond City and the Killens Review of Arts and Letters of the Centre for Black Studies at the City University of New York. She is also founder of Black Women Be Like, a Pan-African womanist podcast.