photo by Trish Nicholson

by Trish Nicholson

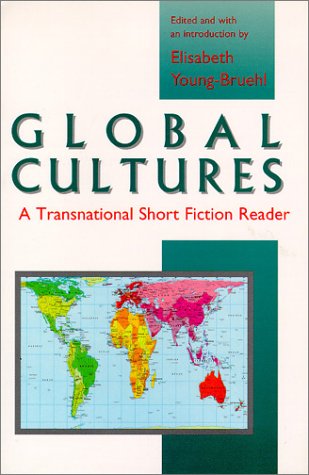

It is little wonder that, as anthropologist and storyteller, I should celebrate human diversity and be inspired by Global Cultures. This anthology’s sixty-one stories offer a breadth of cultural expression far beyond the familiar nods to internationalism in literature that venture no further than Europe and the Americas. Here, even Papua New Guinea is represented, in Epeli Hau’ofa’s satire ‘The Tower of Babel’ – a tilt at the eight hundred languages spoken by Papua New Guinea’s indigenous tribes.

This most culturally diverse of all nations is of particular interest to me: I spent five years working there on the sort of rural development the author mocks so cleverly. Hau’ofa relates the story of a canning project, initiated by the ‘gift in aid’ of a Japanese fishing vessel otherwise destined for the scrap yard. With the help of a foreign ‘Expert’, the locals are coerced into fishing in earnest for this supposedly bottom-up project. Hau’ofa skillfully captures the interplay of donors and bureaucrats whose vested interests combine to bamboozle the unfortunate fellow at the base of the aid-chain. As he does so, Hau’ofa delivers a sideswipe at missionaries:

“A well-rounded Bottom below a well-rounded Top is beauty well worth having,” Manu declared, not thinking of tinned fish.

The responsibility for Bottom Development went to one Alvin (Sharky) Lowe of Alice Springs, Australia. Mr Lowe, a matey-matey sort of bloke who wanted to be known simply as Sharky, was a Great Expert with lifelong experience in handling natives […] He had developed a good feel for the Grassroots, demonstrating it by grabbing every frightened, small-time, part-time fisherman on the beaches of Tulisi and forcing him ever so gently to accept $4,000 in Development Loans from the Appropriate Authorities. And, like the Great Shepherd of Nazareth, Sharky converted many frightened fellows into fishermen.

When problems arise, the Important People – representatives of the Appropriate Authorities – are abroad at conferences or courses, and  eventually the project drains with the sand of the story’s own witty style.

eventually the project drains with the sand of the story’s own witty style.

I delve repeatedly into these tales, and they often lead me to consider how a writer’s voice can be a powerful advocate for change. Nigerian author Chinua Achebe believed that such advocacy and a giving of one’s voice was part of a writer’s duty, to create ‘a different order of reality from that which is given to him’.

Many of the stories in Global Cultures attempt this, their fiction exploring matters of identity, displacement, exile and gender struggles in a post-colonial world. They evoke these realities as an act of survival rather than as an intellectual exercise, and they draw upon the intensity of short fiction to do so. Not surprisingly, war is a frequent theme. Achebe’s story, ‘Girls at War’, reveals not only the spoliation and corruption of war, but also the opportunities for expressing deep moral instincts.

It was a tight, blockaded and desperate world but nonetheless a world – with goodness and some badness and plenty of heroism which, however, happened most times far, far below the eye-level of the people in this story – in out-of-the-way refugee camps, in the damp tatters, in the hungry and bare-handed courage of the first line of fire.

In his parable ‘Masks’, Korean writer Hwang Sun-Won tells of a soldier killed by the thrust of a bayonet as he lies with a leg wound. His blood penetrates his native soil, nourishing a plant and, through the food chain, the body of the enemy soldier who killed him. The surviving soldier lost a limb in the fray; ambiguity in the story’s conclusion, as to whether his wound is in his upper or lower body, suggests Korea’s predicament of separation into north and south.

A little over half of the stories in Global Cultures are written by women. Their stories remind us that shifting social and political fortunes so often have the greatest consequences for women and children. Yet the domestic complications, identities and relationships that they evoke are familiar to women anywhere. In ‘Story of the Name’ – the only story written in English by Pakistani writer Khalida Hussain – a young woman has been jilted by her lover and responds by immersing herself, to the point of obsession, in her role as sister to her brother and auntie to his children, and by failing to eat.

Time passed in such occupations, and the distance between morning and evening disappeared. Chores were the machine for abolishing Time and Space, as a blotter was for removing ink.

With work there was hunger, a blind incision that stretched inside, within which a fire roared. But in the roaring of the fire there was tranquility. At such moments she would feel her belly glued to her back; her fingers would count the bony ribs; and she would see every bone in her body like her own x-ray. She would find sweet contentment in this.

And in losing time and space and the difference between waking and sleeping, she loses also the knowledge of her own name. As years pass, her condition reverses: she sees in the mirror rolls of flesh hanging from her bloated body and is awakened to retrieve her lost identity: ‘Her eyes came to rest on the eyes of the image. The dots and lines of a word stirred and swam in them’.

And in losing time and space and the difference between waking and sleeping, she loses also the knowledge of her own name. As years pass, her condition reverses: she sees in the mirror rolls of flesh hanging from her bloated body and is awakened to retrieve her lost identity: ‘Her eyes came to rest on the eyes of the image. The dots and lines of a word stirred and swam in them’.

‘The Women’s Baths’, a story by Ulfat al-Idlibi, the founding mother of Syrian literature, vividly depicts the ambivalent role of the grandmother; replaced as a household power by her daughter-in-law, yet revered by her granddaughter as a fount of wisdom on the roles and hierarchies of women. The girl extracts this knowledge while observing the behaviour of both functionaries and patrons when she is taken to the public baths – a tradition which the grandmother stubbornly insists on maintaining – a place, too, where the old lady receives the respect she feels due to her as ‘the mother of the Bey’.

Impossible though it is to do justice so briefly to this rich collection of stories, I cannot resist mentioning two more. In the Vietnamese tale ‘The Pine Gate’, by Thich Nhat Hanh, a writer and Buddhist awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his peace-making role during the Vietnam War, we come to understand the necessity for self-knowledge in a spiritual life.

In the final story, ‘A Way of Talking’, Patricia Grace exposes the unwittingly patronising attitude of a Pakeha (white) New Zealander towards the Maori. Rose, the eldest daughter working away from her Maori home, has acquired a city style of expressing herself – ‘her kamakama ways’ – sometimes embarrassing her less outspoken family when she returns for holidays. Her younger sister takes Rose with her to visit a Pakeha neighbour:

Jane said, “That’s Alan. He’s been down the road getting the Maoris for scrub cutting.”

I felt my face get hot. I was angry. At the same time I was hoping Rose would let the remark pass […] Rose was calm. Not all red and flustered like me. She took a big pull on the cigarette she had lit, squinted her eyes up and blew the smoke out gently. I knew something was coming.

“Don’t they have names?”

“What. Who?” Jane was surprised and her face was getting pink.

“The people from down the road whom your husband is employing to cut scrub.” Rose the stink thing, she was talking all Pakehafied.

“I don’t know any of their names.”

In addition to literary flair displayed in this anthology, there is a raw freshness and depth of vision that comes from voices made potent by extreme experience. These are important stories; the gut emotions behind the daily news we barely understand.

As a reader, Global Cultures enriches my understanding of our common humanity. The often distorted images of ‘the other’ brought to us by global media are refocused through these stories which reveal our shared emotional and physical needs. But each culture determines whose needs are met and at whose cost, creating challenges and choices different from our own. As a writer, I am spurred to stretch beyond the familiar, to recognise and evoke these ‘other voices’ in the stories I write.

One thought on “Global Cultures: Stories from Beyond Our Daily News”

Comments are closed.