photo by Jinterwas

by J.K. Fox

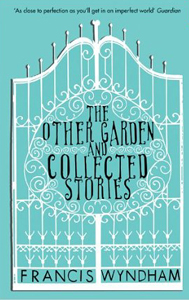

It was only after my mother had given me the book for Christmas that she made her shy confession: “you know, I tried a couple of the stories and they seemed a little… boring.” For me, though, Francis Wyndham’s The Other Garden and Collected Stories is a symposium of quiet elegance and profundity.

It speaks to both the shy child and the private adult within me, capturing as it does all the permutations of human behavior caught between the walls of middle class British society. The people in these stories will not battle vampires or take a psychotic turn in a bizarre first person narrative. They will go to lunch or back to boarding school. They will eat an éclair with a fork. But as with any meaningful portrait, the prosaic situation is merely the foreground. It is the subtle movements of spirit that catch the eye, the motions behind the manners. Wyndham’s prose, as reserved as it is articulate, probes the everyday and comes up with riches. In short, The Other Garden and Collected Stories is not by any measure a boring book.

This moderately sized collection is broken into three sections. There are the two collections of short fiction, Mrs Henderson and Other Stories, first published in 1985, and Out of the War, first published in 1972. These two works bookend Wyndham’s only novel, The Other Garden, which was published in 1987 and won the now disbanded Whitbread first novel award that same year. Excluding the space allowed to Allan Hollinghurst and his short but lucid introduction, these pages represent the sum total of Wyndham’s fiction output (though he had a long and fruitful career as a publisher, journalist and editor).

This moderately sized collection is broken into three sections. There are the two collections of short fiction, Mrs Henderson and Other Stories, first published in 1985, and Out of the War, first published in 1972. These two works bookend Wyndham’s only novel, The Other Garden, which was published in 1987 and won the now disbanded Whitbread first novel award that same year. Excluding the space allowed to Allan Hollinghurst and his short but lucid introduction, these pages represent the sum total of Wyndham’s fiction output (though he had a long and fruitful career as a publisher, journalist and editor).

It is strange to think that this blue and black bound book represents more than forty years of fiction work, and if you were to sweep a casual eye over this not-extensive oeuvre, you might think that here is a man confined by certain thematic walls. While it is true that each work strikes its own individual tone, Wyndham seems uninterested in deviating from a specific time period or social setting.

The stories oscillate within the heart of the 20th Century, in rather middle class settings populated by rather middle class people; there is the school, or the manor house, the cinema café, or the tidy front room; there are the little boarding school boys and the reserved, quietly heartsick adults who teach them. Most of the stories never raise their tempo above a soft whistle or a private smile, but oh, what a world it is. The slimmer waistline of this book is a tribute to Wyndham’s mastery of nuance. Where some would use fifteen brush strokes, he will use one. As a consequence his portraits are all the more compelling for their minimalism, and the occasional sting in the tail feels all the more poisonous.

The title story of the first collection, ‘Mrs Henderson’, is about two boys, the narrator and his friend Henderson, at an unnamed Oxfordshire boarding school. The prose carries the double tone of childish straightforwardness and adult, melancholic retrospection. We know that at the time of the story the narrator is ten years old, and the incidents are delivered with a ten year old’s naïve accuracy. We are told that at this school ‘everyone was always hungry’, that they had to wear ‘stiff grey shorts’ to go out to tea and that the narrator isn’t terribly sure where babies come from but he is quite certain they don’t come out of women’s navels. At the same time, there is an over arching adult voice, describing a child’s perception, with an adult’s vocabulary, the sinister figure of the dormitory master.

His baggy tweed plus fours stank of stale tobacco, sweat and excrement; even his white hair and moustache had yellow stains as if splashed by his own urine. While one of his shaking hands was visibly engaged in a game of ‘pocket billiards’, the other would jerk out unexpectedly to tweak the nape of pupil’s neck.

The sum effect, for me, is quite chilling. Here is an adult looking back at childish days, and trying to reconcile troubling things. And the things in this story are indeed troubling. There is no violence, there is no grand reveal, there is no reconciliation; there is simply a glimpse of a passage of time, time we know will continue even after Wyndham draws the curtain.

Both Mrs Henderson and Other Stories and The Other Garden are the products of Wyndham’s later life. Accordingly, both works show a certain world-weariness and subtle blend of bitter sweet. Wyndham’s life had navigated away from his 1920s English childhood, from World War II and the TB that saw him invalided out of the army. By the time these pieces were published, he had established a life in the world of literature and journalism, a life of editing with a reputation for impeccable taste and criticism. In short, these narratives feel the benefit of someone who not only has an intuitive grasp of people and the messy ways of the heart, but who has also witnessed enough of life to be fluent in its imperfections. The stories pass between them a baton of unsaid things, unhappiness left inarticulate and unexpressed in action. Having said that, they are by no means solely depressing. Jack in ‘The Half Brother’ seems to set the norm for most of Wyndham’s characters and their emotional profile:

Both Mrs Henderson and Other Stories and The Other Garden are the products of Wyndham’s later life. Accordingly, both works show a certain world-weariness and subtle blend of bitter sweet. Wyndham’s life had navigated away from his 1920s English childhood, from World War II and the TB that saw him invalided out of the army. By the time these pieces were published, he had established a life in the world of literature and journalism, a life of editing with a reputation for impeccable taste and criticism. In short, these narratives feel the benefit of someone who not only has an intuitive grasp of people and the messy ways of the heart, but who has also witnessed enough of life to be fluent in its imperfections. The stories pass between them a baton of unsaid things, unhappiness left inarticulate and unexpressed in action. Having said that, they are by no means solely depressing. Jack in ‘The Half Brother’ seems to set the norm for most of Wyndham’s characters and their emotional profile:

He had loved, but been shy of, my father, and their relationship had never really emerged from a crippling cocoon of emotional reserve. With my mother he could be more comfortably-even cosily-affectionate…

Where there is shadow, there will also be the hint of light; these characters have mixed measures of comfort and discomfort. They are whole, all the more so for their imperfections and their emotional reserves that remain untapped.

What is so special about these depictions is that they are not gratuitous in anyway, there is no sex scene thrown in to grab the attention, no meaningless, forced mystery ending, no deliberately depressing fade out. There is no political agenda. This is life in all its dusty, middle of the road poetry. The everyday setting and preoccupations of Wyndham’s creations were not for lack of inspiration, he was a writer who deliberately set out to study the prosaic. He wished to, as he expressed it,

…write about the hours and hours and hours, the enormous proportions of life which is spent in a kind of limbo, even in people’s active years. It seems to me that it isn’t sufficiently celebrated.

The final story collection, Out of the War, maintains these standards. However, because they were Wyndham’s first fictions, they carry a rather studied air. Throughout these narratives, written when Wyndham was a young man, it feels as though we are watching him practice his chosen art. This is the master in the studio. Even the names conjure the image of a still life sketchbook:‘Saturday’, ‘The Visitor’, ‘Going to School’. The story arcs are shorter and simpler than the rest of Wyndham’s fiction. They have a paired down cast; a couple meet and part on a bridge, a child is introduced to a stranger and then leaves the room, a school master says goodbye to his students. At times, a character will be mentioned in one story and then reappear in the foreground of another, creating the feel of a community under scrutiny. These stories are far shorter and in some ways their effects do not linger in the same way the later pieces do. They serve, though, as part of the lovely whole. Each piece remains a valid and rewarding reading experience, a powerful evocation of the words of Thorton Wilder when he wrote that the purpose of literature is the ‘notation of the heart’.

Familiarity goes straight to the heart, even if it is only the resonance of a boring Sunday afternoon, or an awkward meeting in a quiet front room. Wyndham’s stories are little windows of introspection, casting a half-light on the quiet revolutions of my own days. Like sweet sherry or late afternoon lemonade, Wyndham may be an acquired taste, but it is a taste well worth acquiring.