('Saijo City-The Bridge' © Seb, 2008)

FOR SIX CUPS OF COFFEE

by MADELEINE McDONALD

I approached my job interview in the Swiss city of Basel on a wing and a prayer, unsure whether a German A-level qualified me to claim that I spoke fluent German. Brief contact with hotel staff and a tram driver sent my confidence plummeting to zero. The Swiss are multilingual. Not only does the country have four official languages (German, French, Italian and Romansh) but the two thirds of the population registered as German speakers prefer to speak their native dialect, using standard German only for written documents or communication with foreigners. There are at least twenty recognised variations of Swiss German, a mosaic of overlapping tongues stretching from Basel to Saint Moritz. So when my future boss spoke to me in a language I recognised, I almost fell to my knees in gratitude.

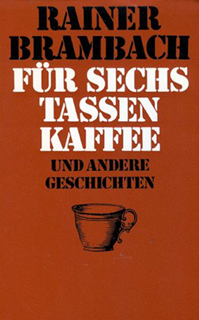

Soon after, browsing in a second-hand bookshop, I discovered For Six Cups of Coffee and Other Stories, by Rainer Brambach, a Swiss author and poet. The collection is published in German only, but like much of the Swiss literature I had started to explore, its simple sentence structures and vernacular turns of phrase make for easy reading

Thinking in one version of a language and writing in another contributes to Swiss-German authors’ distinctive style. Moreover, even lightweight crime fiction is edged with a fierce national pride. This is characterised by one phrase from a memoir that lodged in my mind. It encapsulates a family’s stubborn pride in everything Swiss: ‘On Swiss-made shoes, we climbed the Matterhorn.’ Naturally, shoes from any other country would be considered inferior. As a Scot, I understood a small country’s need to culturally assert itself against its larger, more powerful neighbour to the North.

Thinking in one version of a language and writing in another contributes to Swiss-German authors’ distinctive style. Moreover, even lightweight crime fiction is edged with a fierce national pride. This is characterised by one phrase from a memoir that lodged in my mind. It encapsulates a family’s stubborn pride in everything Swiss: ‘On Swiss-made shoes, we climbed the Matterhorn.’ Naturally, shoes from any other country would be considered inferior. As a Scot, I understood a small country’s need to culturally assert itself against its larger, more powerful neighbour to the North.

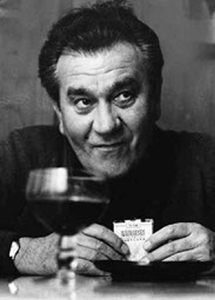

Brambach’s stories are vignettes, some a mere two pages long. His sparse, restrained, laconic prose sheds light on lives lived on the margins of prosperity. In part, this reflects the author’s own chequered path through life. Born in 1917, his youth was marked by unsettled times and his early career included stints as a furniture packer, gardener and house painter. Yet his natural talent could not be suppressed. He found work as an advertising copywriter and began to publish poems and short stories in the 1950s. He received several prizes and honours in his lifetime, from the Hugo Jacobi Foundation Prize in 1955, to the prestigious City of Basel Culture Award in 1982. The stories in this collection are snapshots of the disappointments of life and their effect on the protagonists.

Brambach’s stories are set in the city, not the countryside. Although they include specific references to Basel, his home city, the protagonists could be plucked from life in any large town. He describes the morning rush hour in Basel as ‘…an orderly disorder on the way to the relentless time clock in the office, laboratory, building site or factory’.

Switzerland is the wealthiest country in Europe, yet anyone exploring Basel cannot help noticing pockets of shabbiness. As in any rich city, the homeless and dispossessed are there too, hidden in plain sight, pleading for small handouts such as a free cup of coffee on a wet morning. The first story, ‘For Six Cups of Coffee’, concerns one such character: a homeless man who finds a hundred dollar banknote. ‘He had not trodden in dog dirt as he so often did, no, there, right next to the turf edging the path, lay a brown leather wallet.’ After finding the money, he plots revenge when a coffee stall owner cheats him out of its true value.

Although Brambach, who came from a German family, grew up in Basel and later became a Swiss citizen, he spent a part of his early life in Germany, and during the Second World War he was briefly interned as a German national. This provided the background for ‘Choir Practice’, a description of the bleakness, menace and petty squabbles of prison life. ‘Choir practice was held in the basket-weaving workshop, a small, dismal room which smelled of willow and shrivelled leaves, even with the windows open.’ The unnamed narrator joins the choir as an alternative to ‘looking at the naked lamp, the high-set window and four bare walls.’ He describes other inmates, and tries not to listen to the mutterings of the paranoid choir conductor. He muses on his own situation. ‘You’re more than forgotten. You’re a dead man.’ Instead of joining the choir for the Christmas concert, he returns to his cell and loses his own fragile grip on sanity.

In ‘Justus, or Attics are Hot in Summer’, the unnamed narrator climbs ten flights of stairs to visit the impecunious and slovenly Justus, whose room lies at the top of a house in the industrial quarter: ‘…the kind built shortly before the First World War, grey and sullen on the outside, the stairwell a musty shaft of plaster and linoleum.’ Justus recounts a tale of woe, about his reconciliation with an elderly uncle who owned an air-conditioned flat, their subsequent estrangement and the loss of his inheritance. The narrator watches Justus swat at flies and pee in the gutter. Before he takes his leave, he stubs his cigarette out in an empty sardine tin, and lends Justus ‘a small banknote’, knowing he will never see the money again. ‘Somehow I admire Justus for the very fact that he manages to keep his head above water although he never sells a line.’

The centre of Basel is prettified and medieval, with a painted town hall and steep alleyways, but beyond the old city walls lie rows of tidy streets with listless trees and uniform facades. Brambach excels at depicting snippets of life in these streets, where even foreigners and the down-at-heel must respect the injunction not to prop bicycles against the walls, and put their rubbish out on the correct day, or risk the wrath of the neighbours. The Swiss are a practical nation, and the petty regulations that foreigners mock were formulated to enable city dwellers to live cheek by jowl without too much conflict.

In ‘Känsterle’, which is now a set text in some German schools, a wife nags her husband because their old-fashioned wooden double glazing is unpainted and poorly maintained compared to that of their industrious neighbour. When she demands that he dress as Santa Claus for their children, he is driven to breaking point. Wearing the ill-fitting costume and oversized boots, he falls down the stairs, only to be chided by his wife. He slaps her in front of their children, then smashes her prized ornaments and the contents of the crockery cupboard. Lastly, ‘The rubber plant, together with its pot, flew through a double-glazed window; it exploded in the street.’ The reader understands that Känsterle and his wife have lost all meaningful communication, being reduced to recrimination and grumpy acquiescence. The industrious neighbour is the one who gives him a sympathetic look.

In ‘Känsterle’, which is now a set text in some German schools, a wife nags her husband because their old-fashioned wooden double glazing is unpainted and poorly maintained compared to that of their industrious neighbour. When she demands that he dress as Santa Claus for their children, he is driven to breaking point. Wearing the ill-fitting costume and oversized boots, he falls down the stairs, only to be chided by his wife. He slaps her in front of their children, then smashes her prized ornaments and the contents of the crockery cupboard. Lastly, ‘The rubber plant, together with its pot, flew through a double-glazed window; it exploded in the street.’ The reader understands that Känsterle and his wife have lost all meaningful communication, being reduced to recrimination and grumpy acquiescence. The industrious neighbour is the one who gives him a sympathetic look.

This is a collection where the author stands back, observing, inviting readers to eavesdrop alongside him and draw their own conclusions. In ‘No Post for Miss Anna’, a municipal gardener realises that the postman who stops to pass the time of day and pester him with questions about vegetable growing is jealous of Miss Anna’s boyfriend, a foreigner, and is stealing the boyfriend’s letters to her. The young man has been called home to a family emergency and Anna waits for the postman every day. The gardener does not intervene, either to offer hope to Anna or to reprimand the culprit. Like the author, the gardener observes other people’s frailties without interfering. All he says to the postman is, ‘Once I’ve turned the compost, this job’s finished. I’m not here tomorrow.’

In ‘A Case for Headshaking’, a short memoir, the author describes his early efforts at becoming a writer. Like all true storytellers, Brambach romanticises his own past, and the memoir concentrates on the events of a single night. As he tells it, he resigned from his job as a copywriter as soon as he sold his second story, believing that his pen would offer him a living.

Down I sat at my table and rode my Pegasus, saddled and bridled with splendid intentions, right into a cul-de-sac.

A sentiment that will be familiar to all budding authors. Frustration drives the would-be writer to roam the streets before dawn, losing his money in a cigarette machine. Luckily, for us readers, he returns home to continue the work of writing ‘a handful of poems and tales’.

~

At age 20, Madeleine McDonald fell into translation by accident. Her first boss instructed her to read the King James Bible for 10 minutes on arrival at work, to improve her English. This eccentric approach was successful and she later worked as translator and editor for UN organisations. She has also written newspaper columns, short stories, poetry and radio pieces. Her third novel, A Shackled Inheritance, was published in 2016.