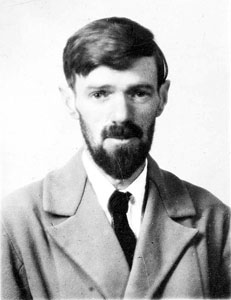

photo by Eric Wagner

by Stephen Devereux

Flame-lurid his face as he turned among

the throng of flame-lit and dark faces upon the platform.

So begins D. H. Lawrence’s ‘Fanny and Annie’. It is, I would argue, one of the best short story openings in English. What does it tell the reader? Nothing. And everything. The image of a man’s face, lit by fire light, amongst a group is precisely and powerfully evoked but, initially, we do not know who the man is or who is observing him.

Lawrence rearranges standard syntax by telling us that something is flame-lurid before we know what that ‘something’ is. We can guess from the word ‘platform’ that the setting is a railway station and the use of ‘he’ gives a familiarity to the character, involving the reader in a way that beginning with a name would not. Next, we are told that the light is from a furnace and that it is ‘she’ who sees him in that light. She sees his face ‘drifting’ and as ‘a piece of floating fire’ because he is looking for her but hasn’t seen her yet.

Out of nowhere, we are then plunged into ‘her’ innermost being before we have any idea who she is. We are told, ‘the nostalgia, the doom of home-coming went through her veins like a drug’. The oxymoronic effect of combining ‘doom’ with ‘home-coming’, and the simile of a drug, create the most precise evocation of the complicated mix of emotions awakened by returning to a place that was once home. Lawrence makes us share in this emotion before we know anything about the character or her motives. There is no context, no limitations of circumstance that could reduce the impact of those words.

In the paragraphs that follow, we are given a detailed description of ‘him’, but always from ‘her’ perspective. We discover that he is called Harry, that he wears a ‘common cap’, a ‘red-and-black scarf knotted round his throat’. His use of East Midland dialect –  “Tha’s come, has ter?” – confirms not only his working class identity, but also his apparent disdain. She notices that he has not even bothered to put on a collar. And then, before the story proper has begun, there is another of those breathtaking flashes of insight into her mind. As she watches him ‘clambering’ into the carriage to get her luggage ‘[h]er soul groaned within her’ at the sight of his animal-like movements. The scene is still lit by the sparks from the furnace behind the station, which light up the twilight sky, and, again, we are told that ‘her spirit groaned dismally. She doubted if she could bear it’.

“Tha’s come, has ter?” – confirms not only his working class identity, but also his apparent disdain. She notices that he has not even bothered to put on a collar. And then, before the story proper has begun, there is another of those breathtaking flashes of insight into her mind. As she watches him ‘clambering’ into the carriage to get her luggage ‘[h]er soul groaned within her’ at the sight of his animal-like movements. The scene is still lit by the sparks from the furnace behind the station, which light up the twilight sky, and, again, we are told that ‘her spirit groaned dismally. She doubted if she could bear it’.

What follows is another abrupt change of perspective within the narration: ‘Let us confess it at once’. This is the signal for a shift to a lofty omniscience that takes us away from the symbolism, the hints, the insights of the opening paragraphs, towards a straightforward telling of the situation. We are told that ‘she’ is thirty, that she has been a lady’s maid, and she has been jilted by her ambitious cousin. She is returning to her home town to marry ‘her first-love, who had waited – or remained single – all these years’.

In this simple line, Lawrence’s choice of ‘confess’ makes a knowing nod towards his tantalising opening, with the unnamed figures in the furnace light, the glimpses of a woman’s innermost thoughts; he now acknowledges the need to explain, to reveal. But why ‘us’? Is he simply pluralising the identity of the narrator, or does that ‘us’ mean the storyteller and the reader? I prefer this explanation because I feel that, from the outset, Lawrence is establishing a confiding, collaborative relationship with his readers.

Fanny and Harry must walk through the ‘sordid’ little town, past the queue outside the cinema, past his friends who call out to him knowingly – more excruciating humiliation for her. She offers to carry some of her luggage and he, ungallantly, gives her one of her cases to carry. We are told: ‘And thus they arrived in the streets of shops of the little ugly town on top of the hill. How everybody stared at her; my word, how they stared!’ Having seen Harry from Fanny’s perspective, we are now shown the community’s response to her return.

When they arrive at Fanny’s aunt’s house, Harry leaves to make arrangements. As the two women talk, it becomes apparent that the aunt thinks that Fanny is treating Harry unfairly. Both women mention his ‘waiting’ for Fanny several times. At this point, the narrative focus shifts to the aunt so that we finally see Fanny from someone else’s perspective. We discover that she is ‘beautiful: tall, erect, finely coloured, with her delicately arched nose, her rich brown hair, her large lustrous grey eyes. A passionate woman – a woman to be afraid of’. This is not at all what I inferred from the insights into her thoughts at the beginning of the story; Lawrence is compelling the reader to rethink her situation.

When Harry returns, Fanny goes down to meet him. At this moment there is ‘a woman’s common vituperative voice crying from the darkness of the opposite side of the road…’ And the voice uncomfortably echoes Harry’s first words to Fanny: “Tha’rt theer, are ter? I’ll shame thee, Mester. I’ll shame thee, see if I dunna.”

Once again we have to adjust our expectations, our sense of what kind of story this is. Fanny says nothing, asks no questions until Harry is having his tea. But when she asks him about the woman, he offers no explanation. Nor does Lawrence. Instead, we are told that Harry is attractive to women, that he is not naturally coarse, but that he is stubborn and lacks ambition.

The following day Fanny meets Mrs. Goodall, Harry’s mother. She is a brilliant evocation of a strong, self-confident, working class woman. She is annoyed at her son for rekindling his relationship with Fanny, but, at the same time, flattered by her interest. Fanny has money and is of a higher status than the Goodalls. Fanny is compelled to listen as Mrs. Goodall berates her for coming back, and Harry for accepting her. Lawrence’s rendition of Mrs. Goodall’s words is extraordinary:

I says to him, “Tha looks a man, doesn’t ter, at thy age, goin’ an’ openin’ to her when ter hears her scrat’ at the gate, after she’s done gallivantin’ round wherever she’d a mind. That looks rare and soft.” But it’s no use o’ any talkin’: He answered that letter o’ thine and made his own bad bargain.

I wince for Fanny as she sits silently listening to her future mother-in-law depicting her as a desperate animal, scratching to be let in the gate. Yet the marriage is arranged.

I wince for Fanny as she sits silently listening to her future mother-in-law depicting her as a desperate animal, scratching to be let in the gate. Yet the marriage is arranged.

In the climax of the story, Harry is singing at Harvest Festival in the chapel where they are to be married in two weeks. As Fanny watches him, listens to his mispronunciation of the words of the hymns, we are given another insight into her heart. We learn of her ‘fatal despair’. As she looks at him, we discover that she ‘hates’ being physically attracted to him, but that he was the first man to kiss her and that those kisses ‘had lived in her blood and sent roots down into her soul’.

This links the ‘doom’, which rushed through her ‘veins like a drug’ in the opening paragraph, more definitely with Harry. Something more than a kiss is implied; she feels like ‘a bird which some dog has got down in the dust’ – almost an image of rape.

On this note, we see again the woman who shouted across the street in the night. She is in the congregation:

You look well, standing there in God’s holy house… bringing your young woman here with you, don’t you. I’ll let her know who she’s dealing with. A scamp who won’t take the consequences of what he’s done.

It transpires that the woman is Mrs. Nixon, the mother of Annie who is single and pregnant (Annie herself never appears in the story). Fanny makes no immediate response, but challenges Harry on the way home. He says only that the child is his “as much as anybody else’s”. We were given hints of such possibilities when Lawrence told us that Harry ‘had waited – or remained single – all these years’. Perhaps the flames of the opening sentence symbolise his virility, his sexuality; though we make that link only now.

Fanny must surely cancel the wedding. She has independent means. She does not need Harry to support her. We hear the gossip spreading through the town. Yet in the penultimate line, Fanny calls Mrs. Goodall ‘Mother’, implying strongly that she still intends to marry.

But why? At the moment when we most need to know Fanny’s thoughts, Lawrence shifts the perspective once more, gives us only her words, leaves us to work it out, just as we have had to do throughout the story…

Of course, like most readers, I have imagined my own explanations for Fanny’s decision to stay with Harry. The story could be read as an essay in sexual politics: Harry’s guilt will be a means by which Fanny will be able to exert her power over him and over his mother. She will no longer be the bird pinned down by the dog. Or perhaps she sees this as an opportunity to confound the gossiping, inward-looking, judgmental little town. Or maybe, is it that his probable fathering of a child is a confirmation of his fecundity, that he has become even more attractive to her as a man? But who can tell? One of the many delights of this story is that it compels us to think, that it does not end with the final word. Each reader must draw their own conclusion.