photo by Tom Woodward

The Short Story Element of

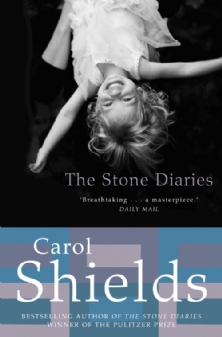

Carol Shields’ The Stone Diaries

by Ruba Abughaida

The Stone Diaries, published by Carol Shields in 1993, is a narration of the life of Daisy Goodwill (and then Daisy Goodwill Flett). It begins in 1905, a short time before the day she was born in Manitoba, and ends slightly after the day she died, in her nineties, in a nursing home in Florida.

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, Canada’s Governor-General’s Award, and shortlisted for the Booker Prize, it is a rich story of the ordinariness of life. It was written as a novel and certainly includes the characteristics of a novel: presenting Daisy’s life as an ongoing discourse that connects her past to her future, taking us as readers on a deep journey into the lives of the characters, using plot to drive the protagonist’s story forward. Yet it arguably includes a strong short story element to its structure and narrative.

While a novel may take its time in building up a story and must necessarily set out clues for the reader, like crumbs of bread along a trail as it progresses, a short story must get straight to the point without any preamble or meandering. Shields achieves this from the first few sentences and then continues to do so throughout; in fact she does it so well that the first few words remained with me long after the book was finished:

My mother’s name was Mercy Stone Goodwill. She was only thirty years old when she took sick, a boiling hot day, standing there in her back kitchen, making a Malvern pudding for her husband’s supper.

The book is divided into ten chapters that have as their title each of the main turning points in Daisy’s life. It begins with ‘Birth’ and moves through to, among others, ‘Marriage’, ‘Motherhood’, ‘Work’, then interestingly ‘Sorrow’ and ‘Ease’, before the final story of ‘Death’. Shields includes the year, at the beginning of each story, when each of these life events took place, and this serves to give a sense of the time and period in which Daisy lived. We know from various interviews that Shields had this goal in mind while writing, and it is the division of chapters in this way which also lends a short story flavour to the book.

The book is divided into ten chapters that have as their title each of the main turning points in Daisy’s life. It begins with ‘Birth’ and moves through to, among others, ‘Marriage’, ‘Motherhood’, ‘Work’, then interestingly ‘Sorrow’ and ‘Ease’, before the final story of ‘Death’. Shields includes the year, at the beginning of each story, when each of these life events took place, and this serves to give a sense of the time and period in which Daisy lived. We know from various interviews that Shields had this goal in mind while writing, and it is the division of chapters in this way which also lends a short story flavour to the book.

Shields undertakes a process of cataloguing Daisy’s life over the course of the novel. However, she does it in a series of observations, about the details of her life within larger life events – making each of the sections strong enough to stand as separate stories on their own. This act of observing is also very much within the realm of a short story.

Shields’ writing is so well crafted that she even manages to make the same cast of characters, that run through the book, appear new and fresh with each chapter. They appear with ease and enough of an introduction to make it possible to read just one chapter, as a complete story, and still get a full sense of who they are; their past and their present.

According to Hernáez Lerena in the Journal of English Studies, Volume 5-6:

There seems to be agreement that the only condition of coherence necessary for the short story is a pointing to the evasion of meaning in life [...] the genre allies itself to the way in which the past is attached to our memory.

This is true of each of the stories (or chapters) in The Stone Diaries. We understand that Daisy tells us about her life in an attempt to make sense of it all. Shields allows us as readers to participate in putting together the jigsaw puzzle of each of the relevant events so that what emerges is a portrayal of a woman who has lived without a true voice of her own – defined by others as a daughter, then a wife and a mother. She doesn’t quite come to terms with all of this, watching her world stray off course, unable to take control and guide it, until it all catches up with her:

It happened overnight, more or less. Her family and friends stood by helplessly and watched while her usual self-composed nature collapsed into bewilderment, then withdrawal, and then a splattery anger that seemed to feed on injury. She was unattractive during this period. Despair did not suit her looks. Goodness cannot cope with badness.

We are unsure if she even knows what she wants, and this sense of dissatisfaction is given the opportunity to work itself in each separate life event she encounters. Shields builds a story out of and around each one and the mood and tone leaves room for us to imagine and conclude on our own, much like we would when reading a short story.

Hernáez Lerena goes on to say that:

The short story is seen as an unfinished narrative product: it traces the lack of “jointedness” of experience, it finds and revolves around a situation which makes life’s reassuring continuity recede from view. It dismantles the notion of the “sequential self” because it negates continuity; always ecstatically pointing at a mystery or a paradox.

The Stone Diaries precisely lands on the definition of the short story as an unfinished narrative product. Even though Daisy’s narrative begins with birth and ends with death, which in themselves are full circle narratives, because she does not view her life as complete and fulfilled, we are also left with a sense that each of her stories are unfinished.

The Stone Diaries precisely lands on the definition of the short story as an unfinished narrative product. Even though Daisy’s narrative begins with birth and ends with death, which in themselves are full circle narratives, because she does not view her life as complete and fulfilled, we are also left with a sense that each of her stories are unfinished.

In terms of narrative structure, Daisy is not present for most of it, although it is about her experiences. Shields uses a shifting narrative which she brings alive with photographs and documents – such as a stream of letters addressed to Daisy that tell of an event which occurs in her life. The letters make up an entire chapter titled ‘Work’ – we know what happens from the people that write the letters to Daisy but in a clever twist, Shields does not give the reader Daisy’s responses in her own words:

Dear Mrs. Flett,

I’ve read your letter carefully and I can assure you I understand your feelings but I believe Jay explained the paper’s policy to you…

Dear Dee,

I am so terribly sorry about all this and I do agree that the policy of the paper is ridiculous…

Dear Mrs. Flett,

Thank you for your letter. I am afraid, though, I am not at this time willing to change my mind…

We read interpretations of Daisy’s life from her friends and family and in typical short story structure, Shields builds a world of ‘mystery and paradox’ where we are given the opportunity to reconcile different truths as told from different points of view. Just as much is said in that which cannot be narrated as that which can. Shields writes of Daisy that:

All she’s trying to do is keep things straight in her own head. To keep the weight of her memories evenly distributed. To hold the chapters of her life in order. She feels a new tenderness growing for certain moments; they’re like beads on a string, and the string is wearing out.

Shields has described in several interviews that she sees The Stone Diaries as a series of Russian nesting dolls, with the stories nesting within each other, yet each one still capable of standing on their own. For me, it’s the short story element of the separate narratives that makes Daisy Goodwill more profound, private and mysterious.

The short story is all about seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary. When Shields was asked what she thought was ordinary – in an interview with Diane Rehm on Public Radio Washington in 1994 – she rather tellingly answered: ‘Either we’re all ordinary or none of us is ordinary’.