(‘Butchart Gardens‘ © Kwong Yee Cheng, 2014)

ENOUGH TO DRIVE ANYONE MAD:

CHARLOTTE PERKINS GILMAN’S ‘THE YELLOW WALLPAPER’

by ROSEMARY GEMMELL

When a work of fiction receives the comment that ‘such a story ought not to be written’, it surely begs the reader to find out why, especially when the critic claims ‘it was enough to drive anyone mad’. Such was the reaction of a Boston physician upon reading Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ soon after the story’s publication in 1892.

The story is indeed an uncomfortable read at times, as when the heroine – a nameless first-person narrator – is robbed of her creativity and freedom by way of a cure for her melancholy. When considering the manner in which women who suffered from depression in the Victorian era were often treated, ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ is a powerful and disturbing tale about the descent into madness.

The story begins much like the Gothic novels enjoyed at the time, when the narrator and her physician husband, John, take up summer residence in a colonial mansion that has stood untenanted for a number of years. The narrator’s imagination is already engaged by her immediate speculation that the house, if not exactly haunted, has ‘something queer about it’. As well as showing us the young woman’s more romantic, imaginative nature, Gilman also exposes the husband’s exceedingly rational disposition through his scoffing at anything that is unseen or unquantifiable, and his lack of empathy for his sensitive wife.

It is an excellent introduction to the characters’ personalities, allowing the reader an insight into the wife’s lack of power because of the men in her life; her brother is also a physician and agrees with John that she is merely suffering from a temporary nervous depression, or hysterical tendency.

It is an excellent introduction to the characters’ personalities, allowing the reader an insight into the wife’s lack of power because of the men in her life; her brother is also a physician and agrees with John that she is merely suffering from a temporary nervous depression, or hysterical tendency.

Thus begins the young woman’s nightmare, at the mercy of a husband who has no understanding of her need for a creative outlet. Since the story is written in the first person, the reader is allowed only the narrator’s point of view; therefore, we must trust that her perceptions of her situation are correct. She describes her husband as careful and loving, yet tells the reader he scarcely lets her stir ‘without special direction’. Writing has always been important to the narrator, as both a creative pursuit and a way to express her thoughts, but her husband denies her even this activity. Soon, in fact, it becomes apparent that he undermines all of her attempts to make independent decisions. Ignoring her preference for the downstairs bedroom that opens onto the piazza, he insists, instead, that they take the room at the top of the house:

It is a big, airy room, the whole floor nearly, with windows that look all ways, and air and sunshine galore. It was nursery first and then playroom and gymnasium, I should judge; for the windows are barred for little children, and there are rings and things in the walls.

The room is decorated with wallpaper that is a ‘smouldering unclean yellow’, and she tellingly notes that it is ‘stripped off…in great patches all around the head of my bed, about as far as I can reach.’ Early on in the story, we can see how much the detested wallpaper attracts her imagination, as she describes its flamboyant patterns in depressive detail: ‘when you follow the lame uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide.’ It is only now that we learn that the narrator has recently had a baby whom she is unable to care for properly as it ‘makes me so nervous.’ The modern reader deduces what the physician husband cannot, that she is suffering from post-natal depression.

For someone with such a creative imagination, her husband’s antipathy towards her writing only exacerbates her depression, and she is forced to write in secret to ‘relieve the press of ideas’ so that she can rest. The reader feels her despondency when she looks out of the window at the gardens, imagining it to be populated with people strolling along its paths, reminding us perhaps of the equally caged Lady of Shallot. Yet even in this, she tells us that her husband cautions against fancy, that her ‘imaginative power and habit of story-making’ must be checked as a nervous weakness.

Deprived of the natural need to express her creativity, or even to discuss her work with anyone who might be remotely interested, she finally turns inward to focus her imagination on the ghastly wallpaper, within which she now begins to see disturbing images crawling across the walls. Yet she lightly brushes off these imaginative manifestations, telling us that she has always had this tendency to get ‘more entertainment and terror out of blank walls and plain furniture’ than most do children with toys. It is little touches of foreshadowing like this that gives us insight into the character, propelling the story towards its inevitable conclusion.

The arrival of the narrator’s sister-in-law – a ‘dear girl, and so careful of me’ – merely adds another person from whom she must conceal her writing: ‘I must not let her find me writing’ she tells us, adding ‘she thinks it is the writing which made me sick!’ By now, every aspect of housekeeping and child rearing has been taken from her, and our poor narrator sinks more deeply into depression. With her husband attending to his patients in town most days, she is also left alone for much of the time, whether walking in the garden or resting in her room.

The story now takes a more sinister twist. She begins to grow fond of the room, in spite of the wallpaper – or even because of it, and displays a knowledge of design as she minutely examines each curve and flourish from her nailed-down bed. She still believes that her husband loves and cares for her, but when she asks to visit her cousins, he decides she is not well enough and instead carries her back to her bed where he reads to her. Though he does appear very solicitous of her well-being he insists she must get better by using her ‘will and self-control’ and not letting ‘any fancies’ run away with her.

When she mentions the baby again, she is thankful he has escaped the horrible nursery, calling the child ‘an impressionable little thing’ as though he too would have been affected by the room and its frightful yellow wallpaper. Perhaps it is this thought of her baby and her inability to care for him that finally drives her over the edge into an alternative reality. She begins to discern the shape of a woman within the wallpaper pattern, one who is trying to escape from her prison. And of course it is a kind of prison that now holds the narrator captive. Although her husband sleeps in the same room, he calls her ‘little girl’ and refuses to give up the lease when she asks to go home. He assures her that her health is improving, reminding her that he is a doctor and should therefore know, and reinforcing her dependence on him.

The tragedy of the story is that the narrator knows very well that she is not getting better, especially in her mind. When she suggests this to her husband, he will not even allow her to give words to her fears. In fact, he is quite determined that she will not let the idea enter her mind, telling her: “there is nothing so dangerous, so fascinating, to a temperament like yours. It is a false and foolish fancy.” Silently, she lies awake in the moonlight, imagining it is now a woman behind bars contained in the hideous pattern of the wallpaper.

As the days progress, the horror increases and she describes the ‘yellow smell’ that permeates the house. She is certain, too, that the woman in the paper is trying to climb out from her prison, creeping even by daylight in the road under the trees. Her last grasp on reality starts to loosen when she says ‘I always lock the door when I creep by daylight.’ She begins to tear at the paper to help the woman escape, and starts to see through her husband’s concern.

As the story approaches its climax, time is running out. The couple’s lease is up and they are due to leave the house. Instead of being delighted, though, the narrator locks herself in the room and throws the key out the window so that none can disturb her while she frees herself from her wallpaper prison. ‘I’ve got out at last’ she tells John and his sister when they eventually find the key, ‘and you can’t put me back.’

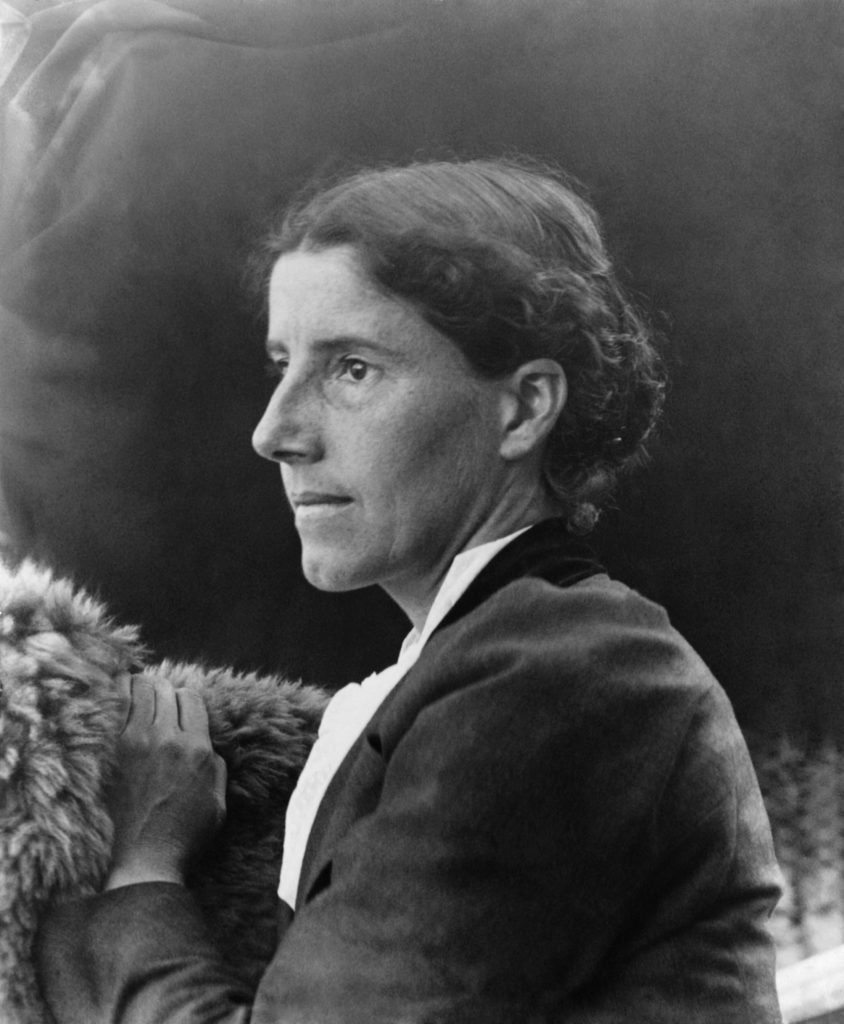

As a story about a woman denied her basic right to express her creativity and to be respected as an equal, ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ exposes the kind of situation many female writers experienced in previous centuries. Although it stands on its own merit, the author has used some of her own life experiences, enlarging and fictionalising them, to write a story that can also be read as a warning. We don’t really need to know that Gilman herself experienced severe post-natal depression and that she was prescribed a rest cure for ‘inappropriate’ ambition, but it may add to our understanding of the way some women suffered – at the hands of their husbands and physicians – when their concerns were dismissed as hysteria.

A short story may entertain, inform or educate, and any writer is pleased if their writing is enjoyed. Sometimes, however, a story might have a more wide-reaching effect on a reader, even many years after it was written, especially if it addresses a subject that large numbers of people have experienced.

The Boston physician who denigrated Gilman’s story as ‘enough to drive anyone mad’, most likely didn’t understand it, but another doctor called it the best description of incipient madness he had seen. Gilman herself was delighted that her short story had an even greater effect when she discovered that a specialist had altered his treatment of neurasthenia after reading ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’. What a wonderful epitaph to the power of creativity.

~

ROSEMARY GEMMELL is a published historical and contemporary novelist from Scotland. Her short stories, articles and occasional poems have been published in UK magazines, in the US, and online and several stories have won awards. Rosemary has a Post-Graduate Masters in literature and history and is a member of the Society of Authors, the Romantic Novelists’ Association, and the Scottish Association of Writers. She blogs about reading and writing, here.

ROSEMARY GEMMELL is a published historical and contemporary novelist from Scotland. Her short stories, articles and occasional poems have been published in UK magazines, in the US, and online and several stories have won awards. Rosemary has a Post-Graduate Masters in literature and history and is a member of the Society of Authors, the Romantic Novelists’ Association, and the Scottish Association of Writers. She blogs about reading and writing, here.