photo © Blue Trail Photography, 2013

by Nicole Mansour

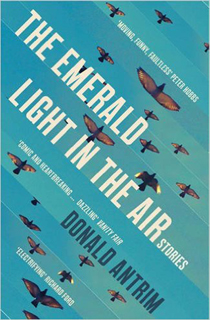

Donald Antrim’s debut collection of short fiction, The Emerald Light in the Air, contains seven stories, all of which prominently featured in The New Yorker magazine between 1999 and 2014. Antrim’s prose is vivid yet uncluttered, bringing to mind the economy of John Cheever, as well as the fairy tale surrealism of Donald Barthelme. Arranged in order of their original publication, the stories clearly reflect Antrim’s own experiences with psychosis and the uneasy, often tragicomic journey endured by sufferers of mental illness.

The collection begins with the antic comedy ‘An Actor Prepares’, in which a middle-aged college acting teacher attempts to stage a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the process, he reveals his own sexual neuroses and romantic disasters.

I felt free and young. I should say that I felt myself backsliding to a younger state of mind. It’s hard to say what this feeling consisted in – panic and hope, disappointment, shame. I was wearing torn Barry Bears gym shorts and feeling like a teenager and running fast, and my feet sank into the earth, and mud splashed my legs. What is more awful and disorienting than adolescence? How had I become so lost and alone? What had persuaded me that I could play a young man’s part?

Here, forty-six year old Professor Reginald Barry contemplates his futile attempts at directing the ill-fated Shakespearean production – thwarted by a series of disasters, including a flash flood and a hostile duck – and ruminates on casting himself as the young Lysander, a rather provoking guise he employs in order to engage in an elaborately staged orgy with a sophomore. Reginald’s bemusing behaviour is shameful and humorous in equal measure, though Antrim ends the story before any serious incrimination has a chance to surface.

Here, forty-six year old Professor Reginald Barry contemplates his futile attempts at directing the ill-fated Shakespearean production – thwarted by a series of disasters, including a flash flood and a hostile duck – and ruminates on casting himself as the young Lysander, a rather provoking guise he employs in order to engage in an elaborately staged orgy with a sophomore. Reginald’s bemusing behaviour is shameful and humorous in equal measure, though Antrim ends the story before any serious incrimination has a chance to surface.

In the stories that follow, surrealism and humour make way for more complex and psychological human drama. In ‘Another Manhattan’, a man struggles with the simple act of buying his girlfriend flowers, as he attempts to maintain his grip on reality between visits to a psychiatric ward. Similarly, in ‘Pond, with Mud’, an alcoholic New Yorker, in a moment of derangement, buys his soon-to-be stepson’s father a drink when they meet him busking on a train station on their way to the zoo.

Could anything have been meaner? Could he have been more cruel? Here was a demonstration of the power of a weak man over a weaker man. And there was more to come, when he shoved the money and the tissues back into his pocket and said, “Can I buy you a drink?” Patrick understood that he was not so much abusing the other man as punishing himself; they would drink together, the two men, and Patrick would buy, and he would get drunk enough to give himself credit for being a generous person. Later in the day, Roger might get up his nerve and punch him; but if he did he might injure his hand and be unable to play the violin for a while, and Patrick would be obliged to help him with a loan. There was no end to it.

Sarcasm and bitterness pervade in protagonist Patrick’s absurd but comical circumstances. He paints a disquieting picture of himself as an alcoholic, of the desperate violinist father he drinks with, and even of the young boy, Gregory, who after waking from an uncomfortable nap atop a bar stool, is given a sip of scotch and soda to prevent him crying. Despite the promise of chimpanzees, the visit to the zoo never materialises, yet somehow the references to the menagerie – unfortunately constructed on marshlands once home to a chemical plant that had since burned to the ground – serve as a lucid and satirical metaphor for the story’s ever-evolving calamity.

This acute degree of absurdity is echoed in many of the pieces. In ‘Solace’, a couple, each with roommate difficulties, only meet in other people’s apartments; the stasis of their situation becomes a metaphor for their relationship. And in ‘He Knew’, a married couple who bonded over their respective mental health disorders struggle to hold on to their inner selves.

It was true, he’d dumped a few too many pills, and some had rolled off toward the condiments, the ketchup and the sugar and the salt and pepper shakers and so forth, and he was missing – what was he missing? He had Alice’s portion under control. And there were his pink-and-yellow antipsychotics. Where had the beta-blockers gone?

The final story, from which the collection takes its name, leaves a feeling of reconciliation rather than resolution: ‘The Emerald Light in the Air’ refers beautifully to both the approaching thunderstorm and the inevitability of bad news:

Someone was coming toward the car. A figure moved between the trees beside the creek. It was a boy carrying an umbrella. He was skinny and wore jeans and no shirt. He stepped down to the bank and splashed across to the car with the umbrella over his head. Billy rolled down the window, and the rain swept in, drenching him.

Set in a murky, wet Southern forest, there is something haunting in the tale of Billy French, an art teacher attempting to recover from a breakdown. He gets lost, then gets his Mercedes stuck in a creek bed. Subsequently, he encounters a family living in a remote cabin, who mistake him for a doctor coming to tend to the mother, dying of cancer. Billy fraudulently plays along despite the family’s doubts, offering the woman, who is clearly suffering, some of his painkillers. Like many of the characters in Antrim’s stories, Billy’s questionable actions emerge from a sense of benevolence: his gesture blurs a line between wrong and right, delusion and eloquence; in a moment of misguided kindness, he becomes both patient and healer.

There are unquestionably traces of Antrim’s earlier work in this collection. His three novels of surrealist high comedy – Elect Mr Robinson for a Better World, The Hundred Brothers and The Verificationist – and his devastating memoir about growing up with an alcoholic mother – The Afterlife: After Death – all amble between chaos and a place of delicate instability, and finally hover upon a moment where all seems destined to fall apart.

Like his earlier work, depression and suicide – or at the very least, the possibility of suicide – run as constant themes through this collection, though the emotional disorientation of the characters feels more pronounced. In an interview with Michael Silverblatt on KCRW’s Bookworm in 2014, Antrim commented on how he arrived at the decision to explore this theme more directly:

“I wanted to articulate in fiction […] the physical experience of a depression that’s going psychotic […] In that time when psychotic depression is going strongly, there is nothing abstract about it at all.”

His characters – intelligent, witty, gentle, generous – are people living under the shadow of a disorder; they are depressive, bipolar, and alcoholic. Yet despite their delusions, bad behaviour and dubious decision-making, they attempt to make do; these are people who do the wrong things but with the best possible intentions. They are often failed artists, or survivors of troubled childhoods and drunken parents.

His characters – intelligent, witty, gentle, generous – are people living under the shadow of a disorder; they are depressive, bipolar, and alcoholic. Yet despite their delusions, bad behaviour and dubious decision-making, they attempt to make do; these are people who do the wrong things but with the best possible intentions. They are often failed artists, or survivors of troubled childhoods and drunken parents.

There is something wonderfully recognisable in these stories – the awkward, laughable pain that comes with reflecting upon, as Antrim says, ‘having your turn in the barrel’. Antrim writes with both kindness and humour; there is a generosity in his depiction of these troubled characters, as they bounce between loneliness, love and insanity.

When I consider fiction that attempts to observe the effects of mental ill health in comic style, I’m often left with a feeling of ambivalence – as if the author were evading the seriousness underlying the external disquiet. But this isn’t the case with The Emerald Light in the Air. For even in those moments of farce and levity, there is a deep eloquence in Antrim’s style that captures the truth behind the action, and breathes life into these remarkably discernible characters. In some cases, these stories seem to end before the tragedy comes and, despite, the inevitable disaster that looms, the worlds of Antrim’s stories remain full – if not always of hope, then definitely of merry laughter.

~

~

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour is a graduate of Actors Centre Australia, a former inhabitant of Buenos Aires, London, Melbourne, and Hong Kong, and is currently completing a BA in Literature. Her essay, ‘Beyond the Barren Landscape: Elizabeth Harrower’s A Few Days in the Country‘ was longlisted for the 2016 Thresholds Feature Writing Competition.