photo © State Farm, 2007

by John Verling

The thing I love about Christmas is the genuine excuse to do nothing. However, last year, by St. Stephen’s Day I hadn’t been outside the front door since lunchtime on the day before Christmas Eve, nearly four days. That afternoon, the cabin fever began to set in…

The couch was no longer as comfortable, the TV was boring, my newspapers were read and I was finding solace in food. A storm was hitting and, even if I felt so inclined, going for a walk wasn’t an option. Before I blew a gasket, I went up to my room for a shower. Afterwards, I was tidying my son’s bedtime books on his little shelf when a faded red, hard-backed and scuffed at the edges book fell into my hands. On its spine I could just make out The Essential James Joyce.

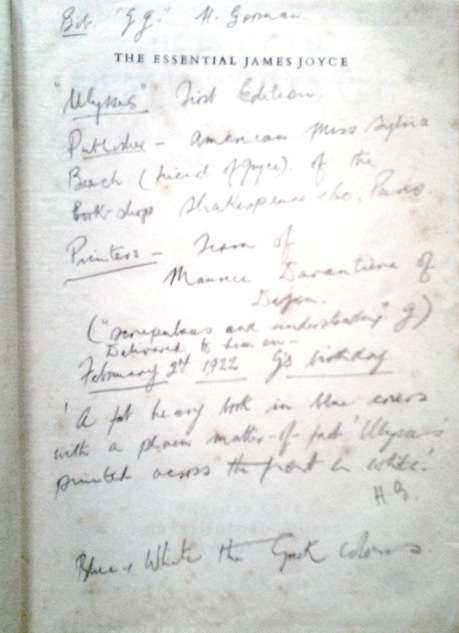

How had that got there? I opened it and there was an inscription on the frontispiece: ‘To Michael, Birthday Greetings 1950, Patrick.’ It had been a present to my father from his brother, an uncle I never knew as he died before I was born. In the book, my father had written notes on Joyce, underlined parts of the preface and sellotaped newspaper cuttings at appropriate places. The sellotape and cuttings were faded yellow by now, but the printed dates of different times in the 1950s were still clear. My father’s firm writing stood out too, adding his own notes and correcting any omissions – in the Editor’s Introduction, Harry Levin had written just ‘Joyce’s father’, which was corrected, in pencil, to ‘John Stanislaus Joyce of Cork’.

Joyce never appealed to me; I once tried to read Ulysses but gave up after about fifty pages. With Finnegans Wake I didn’t get far beyond ‘riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s’. I must have taken this scuffed, red book from my father’s house after he died, probably because of the inscription. It seemed to have all Joyce’s works, except Ulysses of course, and I remembered that ‘The Dead’ was a Christmas short story. I checked the index – the collection Dubliners was there and ‘The Dead’ was part of it.

Joyce never appealed to me; I once tried to read Ulysses but gave up after about fifty pages. With Finnegans Wake I didn’t get far beyond ‘riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s’. I must have taken this scuffed, red book from my father’s house after he died, probably because of the inscription. It seemed to have all Joyce’s works, except Ulysses of course, and I remembered that ‘The Dead’ was a Christmas short story. I checked the index – the collection Dubliners was there and ‘The Dead’ was part of it.

Freshly washed and dressed, I took my new-found book back downstairs. The armchair by the lamp and the fire was free, so with a blanket wrapped round me and the wind howling outside I began to read.

I couldn’t put the book down; I’d never thought of Joyce as a page turner, indeed the old pages were quite thick and slow to turn, but I read ‘The Dead’ in double quick time, totally taken aback by its depth yet its simplicity.

It is a beautiful but sad story of Christmas and human emotion. An annual Christmas dinner party, organised by two maiden aunts, brings the cast together. Familiar to us of any gathering are the interactions between guests and misgivings over some of the invitees. A song sung to celebrate the occasion awakens memories in Gretta who is married to Gabriel, the favourite nephew of the two aunts. Later, Gretta tells Gabriel why the song means so much to her and the tale deeply affects him. A strong, resolute man he now has to see his marriage and his wife in a totally different light, possibly changing their relationship forever.

Joyce writes his characters so easily that it’s not difficult to picture them in front of you. The description of Freddy as the kind of drinker we all know is perfect, as is the idea of him trying to keep his obvious drunkenness under control. The household, run by the two sisters, the dancers, even the cab called to take people home, all fit in perfectly with the plot. As heartbreak is revealed, you can see Gabriel’s suffering as much as his wife’s, how small he felt in her newly revealed life story. Joyce quite simply takes a Christmas gathering but uses it to tell a wonderful story.

Once I had read ‘The Dead’ I moved seamlessly into the other stories over the next few days. What had started out as a distraction became my Christmas. As soon as the night began to draw in I’d curl up on my armchair, blanket wrapped around me and read the great writing.

Much has been written of Joyce’s work, usually very detailed scholarly thought which I find so off-putting. But in this reading I found nothing but real writing from the heart, about very real people. It’s always the mark of a good writer that you believe the characters live on after you’ve finished reading and from Joyce they’re still alive a century later.

A teacher of mine once said that they could rebuild Dublin from scratch just by following Joyce’s writing. This was obvious from his descriptions of streets and the houses on them, bars which may no longer exist or places of business long since closed. For the last  year I’ve had to travel to Dublin at least once a month, but since reading Joyce I now look at the city completely differently. Now I notice street names, notice the buildings on them, take in the new buildings and see how the road layout of the inner city hasn’t changed. While driving down any city centre street I can almost see one of his characters making his way home in the snow after an evening pint. Thanks to Joyce I know which street meets which and where, what pub or shop once stood on the corner.

year I’ve had to travel to Dublin at least once a month, but since reading Joyce I now look at the city completely differently. Now I notice street names, notice the buildings on them, take in the new buildings and see how the road layout of the inner city hasn’t changed. While driving down any city centre street I can almost see one of his characters making his way home in the snow after an evening pint. Thanks to Joyce I know which street meets which and where, what pub or shop once stood on the corner.

Joyce tells tales that may be set in early 20th century Dublin but really they could just as easily be applied to today’s life. He was writing nearly one hundred years ago of events and struggles that are just as relevant today. Workplace depression may be thought of as only emerging in recent years, but Farrington in ‘Counterparts’ hates his job and Joyce writes so well of the disenchantment of the worker with his employment. The monotony of his office job becomes too much and Farrington turns to alcohol to get through his day:

He returned to his desk in the lower office and counted the sheets which remained to be copied. He took up his pen and dipped it in the ink but he continued to stare at the last words he had written: In no case shall the said Bernard Bodley be… The evening was falling and in a few minutes they would be lighting the gas: then he could write. He felt that he must slake the thirst in his throat. He stood up from his desk and, lifting the counter as before, passed out of the office.

The tale of Farrington making his way home through the pubs of Dublin and what subsequently happens at home is very upsetting, but yet engrossing.

Even today’s problems with immigration are mirrored in his writing. In reading ‘A Little Cloud’, we find the character of Gallagher as the immigrant, home on holidays from London, living the high life for a few days. Gallagher talks of the luxuries of living abroad and the freedom of unmarried life. He’s trying to make his old friend Little Chandler jealous and they do things that Little Chandler hasn’t been able to do for a long time, as he is raising a family. All so familiar today to those who’ve stayed home as others went away. The finish to the story would resonate with many young males and the fear of their inadequacies suffered in silence.

The stories are not all about Dublin, though, they just happen to have the city as a backdrop. There is a tale of unrequited love in ‘A Painful Case’, one of kids skipping school in ‘An Encounter’ and one of horrible deception in ‘Two Gallants’. Even though ’After the Race’ is very much of Dublin, I could see it playing out in my native Cork. In fact, probably the reason why so many have liked Dubliners is that, despite its title, the collection could reflect any city or town, anywhere in the world.

Joyce liked his lists, apparently, and every story here has them. What the two sisters have as refreshments for the dancers in ‘The Dead’ made me want to be there, even more so his description of the dinner served later…

A fat brown goose lay at one end of the table and at the other end, on a bed of creased paper strewn with sprigs of parsley, lay a great ham, stripped of its outer skin and peppered over with crust crumbs, a neat paper frill round its shin, and beside this was a round of spiced beef. Between these rival ends ran parallel lines of side dishes: two little minsters of jelly, red and yellow, a shallow dish full of blocks of blancmange and red jam, a large green leaf-shaped dish with a stalk-shaped handle, on which lay bundles of purple raisins and peeled almonds, a companion dish on which lay a solid rectangle of Smyrna figs, a dish of custard topped with grated nutmeg, a small bowl full of chocolates and sweets wrapped in gold and silver papers and a glass vase in which stood some tall celery stalks.

As well as the beauty of his writing bringing the table to life, reading this makes me hungry too and you can almost taste the food he describes. In all his stories, Joyce slips in these lists, almost so that you don’t realise you are reading one, just more layers of a story being built up for your enjoyment. The character Maria does it constantly in ‘Clay’, which tells so many little stories in one tale that you feel you know Maria as if she was in your living room. Of course, I was in my living room, and the characters were coming  and going so much so that I could only read one or two stories at a sitting. Each one had to be dealt with, each person digested and put away before moving onto the next Joyce creation. My family were only incidentals and seemed to know to leave me alone when I had The Essential James Joyce in my

and going so much so that I could only read one or two stories at a sitting. Each one had to be dealt with, each person digested and put away before moving onto the next Joyce creation. My family were only incidentals and seemed to know to leave me alone when I had The Essential James Joyce in my

hands.

Lisa, my wife, must have been fed up with me going on with how great a book I was reading, but I really was like a kid on Christmas morning with my discovery. She heard of observation being Joyce’s strongpoint, how Dublin now made sense to me, even that caraway seeds were once sold in pubs. Farrington, in ‘Counterparts’, had a caraway seed after his glass of porter, the reason for which I had to look up online. He was sneaking out from his hated office job for a glass of porter in O’Neill’s shop, five times in the one day during the telling of the story. Apparently, the caraway was used to mask the smell of alcohol on the breath.

Joyce sees things in people, little things that can turn a story or make one complete. Each story in Dubliners is unique, though there are slight connections between the stories made now and again. By the time my Christmas was over, I felt familiar with each character and wondered what they were doing now. Joyce had taken me in for those five days; shown me a Dublin that may be gone but gave me stories that are very relevant a century later. As an introduction to Joyce, though I had only stumbled upon it, you couldn’t wish for a better one and I will return to it again. It will be my Christmas read once more, my book to pick up during those lazy days when the fireside is calling. My father’s notes, in his careful handwriting, written when he was younger than I now am, reminding me of him and my Christmases as a child. I half expect the cast of characters will have moved on, their lives progressing and there will be catching up to do. Probably not, but who knows with that faded, red, scuffed and very special old book of stories.

One thought on “Dubliners at Christmastime”

Comments are closed.