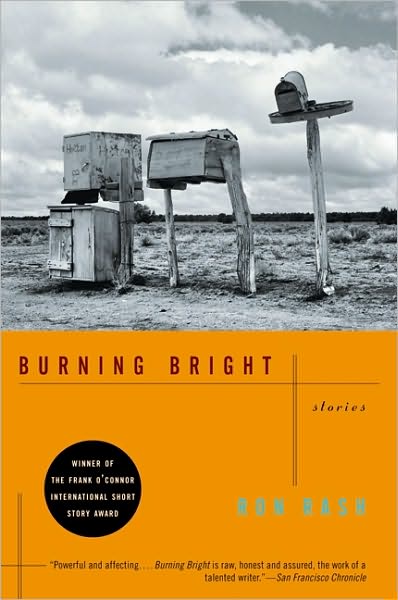

photo by Thomas Wenz

by Kath McKay

A story for our times, ‘Hard Times’ by Ron Rash should be required reading for politicians.

In an article called ‘The Sense of Place’, Rash spoke about how,

the most interesting regional literature is often the most universal. The best regional writers are like farmers drilling for water; if they bore deep and true enough into that particular place, beyond the surface of local color, they tap into universal correspondences.

Most of Rash’s work is set in North and South Carolina, where his family have been settled for over two hundred years. ‘Hard Times’, with its exact local language and detail, is a resonant example of the strength of his outlook.

If short stories are about the human, this story shows us how the human gets squashed by poverty and a lack of hope. A seemingly simple story set in the Appalachians, North Carolina, during the Depression era, ‘Hard Times’ is so sparsely written, reflecting the sparseness of the surroundings and the characters’ situations, it breaks your heart.

A farming couple, Jacob and Edna, have been losing eggs from their bantam for a few days. Everyone around them is suffering, during the ninth year of the US Depression, around 1938. President Roosevelt claims that the economic situation is getting better, but Edna points out they are getting half the price they used to get for crops. Their truck has been taken by the bank and their children have left home. Jacob knows others are worse off. People are hungry, getting shot for looking for work, and beaten with clubs as they hide in boxcars. Their own area had a sawmill, but it closed down, leaving many without work.

A farming couple, Jacob and Edna, have been losing eggs from their bantam for a few days. Everyone around them is suffering, during the ninth year of the US Depression, around 1938. President Roosevelt claims that the economic situation is getting better, but Edna points out they are getting half the price they used to get for crops. Their truck has been taken by the bank and their children have left home. Jacob knows others are worse off. People are hungry, getting shot for looking for work, and beaten with clubs as they hide in boxcars. Their own area had a sawmill, but it closed down, leaving many without work.

The story begins with Jacob standing in the ‘barn mouth’ watching Edna leave the henhouse. This use of the word ‘mouth’ alerts us to the concerns of the story: poverty and hunger. Edna’s lips are pressed tight. More eggs have been taken: a crisis. It’s eight in the morning. In other places there would be ‘full dawn’, but ‘This cove’s so damn dark a man about has to break light with a crowbar, his daddy used to say’.

The imagery is concrete and exact, hard and ringing. Jacob, seeing the set of his wife’s lips, thinks how her smile used to entrance him: ‘Her whole face would glow, as if the upward turn of her lips spread a wave of light from mouth to forehead’. But nobody round this neck of the woods is ‘burning bright’ any more. His wife, embittered and worn down, does not smile. He reminds her there are folks worse off than them. But she stubbornly says, ‘We can end up like Hartley yet’, talking of their neighbour.

Jacob tries to be generous about his wife, knowing she wasn’t always this way: ‘Not until the bank had taken the truck and most of the livestock. They hadn’t lost everything the way others had, but they’d lost enough.’

Edna suspects Hartley’s dog, saying, ‘That dog’s got the look of an egg-sucker’. But Jacob sees no reason to suspect it. He knows a dog would leave egg shells or slobber. He knows it could be a ‘two legged varmint’, but not even Hartley, ‘the poorest of them all’ would steal.

And then the Hartley family, the symbol of how much further Jacob and Edna could fall, come down the trail. They are father, mother, daughter and dog, making a two-mile trek to town to sell galax leaves,

the closest thing to a crop Hartley could muster, for his land was all rock and slant. “You couldn’t grow a toenail on Hartley’s land,” Bascombe Lindsay had once said.

Galax leaves, used in the flower industry, were gathered by poor mountain people for small amounts of money. Hartley used to work at the sawmill, but the family now had only ‘one old swaybacked milk cow to sustain them’, and the galax. Jacob has read in newspapers that,

Rich folks in New York had lost all their money and jumped out of buildings. Men rode boxcars town to town begging for work. But it was hard to believe that any of them had less than Hartley and his family.

Hartley is about to pass when Edna asks if his dog is an egg-sucker. “What’s the why of you asking that?” he asks, and Jacob is struck that ‘even the man’s voice had been worn down to a bare-boned flatness’. Edna tells Hartley of the henhouse thefts.

‘So you reckon my dog,’ says Hartley. And then in one of two shocking scenes in the story, Hartley takes a knife and settles the blade against his dog’s neck, while his daughter and wife ‘stood perfectly still, their faces as blank as bread dough’.

Jacob tries to deflect Hartley, saying he doesn’t think it’s the dog. “It could be,” says Hartley, and slits the dog’s throat. “You’ll know for sure now.”

His family walk on. Jacob rounds on Edna: “You know how proud a man he is.” With everyone around snowed in the winter before, Jacob had tried to gift a salted pork shoulder to Hartley’s family, but Hartley, unable to pay, refused to accept it, even as his family subsisted on ‘gray-colored gruel.’

Edna says killing the dog “wasn’t my intending” and Jacob lashes out verbally, saying she didn’t intend for their children never to visit, “But it happened”.

The next morning, more eggs are missing and this prompts Jacob to recall Edna’s harsh treatment of their children. Six years before she had made their twelve year old son eat dropped oatmeal off the floor. Two weeks later their daughter left, and the boy joined the navy as soon as he was old enough.

The mystery of the eggs unsolved, Jacob consults with acquaintances in town. They decide that a ‘big yaller rat snake’ is the mystery egg sucker, and that the way to catch it is by ‘fishing’.

Jacob prepares his trap – a barbed hook through an egg – and three yards of line attached to a nail head. That way the snake would swallow the whole egg before the line pulls the hook.

Edna is upset at his jibes about the children, saying that they never wanted, and that the world was a hard place:

“There was need for them to know that… They needed to be prepared, and I prepared them … You think I got no feelings … Stingy and mean-hearted. But maybe if I hadn’t been we’d not have anything left.”

Jacob cannot sleep and, when he hears a noise in the henhouse, he takes a hoe, ready for killing. He checks the bantam. No eggs. He follows the fishing line, readies the hoe ‘and saw Hartley’s daughter huddled in the corner, the line disappearing into her closed mouth’.

Rash paints the picture clearly, and the  image tears at your heart, just as the hook tears at the child’s cheek. We feel it going in. But the child, cowed and beaten down by hunger and desperation, does not speak ‘and her eyes do not widen in fear’. Jacob realises he can’t just pull the hook out, but manages instead to push through the barb wedged in her cheek, and only then does she whimper. He dabs her cheek with turpentine and lifts her up, ‘so light it was like lifting a rag doll’, and in her hand is an egg. He lets her eat the egg: “You don’t ever take them home, do you… You eat them here, right?” She nods.

image tears at your heart, just as the hook tears at the child’s cheek. We feel it going in. But the child, cowed and beaten down by hunger and desperation, does not speak ‘and her eyes do not widen in fear’. Jacob realises he can’t just pull the hook out, but manages instead to push through the barb wedged in her cheek, and only then does she whimper. He dabs her cheek with turpentine and lifts her up, ‘so light it was like lifting a rag doll’, and in her hand is an egg. He lets her eat the egg: “You don’t ever take them home, do you… You eat them here, right?” She nods.

Jacob sends the girl home, warning her not to come back, and says he will put a hook in the eggs that would tear her apart. When she leaves, he sits as the darkness lightens ‘to the color of indigo glass’. He informs Edna that it was a snake, goes to bed and closes his eyes, imagining towns where hungry men rode boxcars ‘looking for work that couldn’t be found’, shacks where ‘families lived who didn’t even have one swaybacked milk cow’, cities with sidewalks stained with blood. The final sentence cuts us, making us complicit and shamed that we still have a world where such things happen: ‘He tried to imagine a place worse than where he was’.

Mark Thomas in The Canberra Times has said that, for Ron Rash, a short story is:

less a synopsis than a synthesis, a short-form distillation of a moment that matters, written with the concise precision demanded of poetry but opening up other people’s worlds in the way which novels do. His stories are really epiphanies, studies of the defining occasion when character is exposed and fate determined.

Read him.

~

Kath’s stories appear on www.cutalongstory.com. They have been anthologised, won competition prizes and Arts Council awards, and been on Radio 4. She has written on Flannery O’Connor and Tim Winton. A second poetry collection, Telling the Bees (Smiths Knoll, 2014) will be followed by Collision Forces (Wrecking Ball Press). She teaches creative writing at Hull University.

Kath’s stories appear on www.cutalongstory.com. They have been anthologised, won competition prizes and Arts Council awards, and been on Radio 4. She has written on Flannery O’Connor and Tim Winton. A second poetry collection, Telling the Bees (Smiths Knoll, 2014) will be followed by Collision Forces (Wrecking Ball Press). She teaches creative writing at Hull University.