photo by zizzybaloobah

by Mike Smith

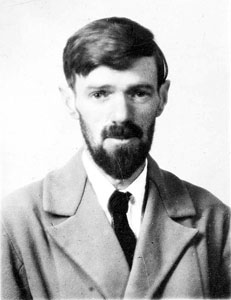

Ask most people and, I suspect, they will tell you that D.H.Lawrence was a famous English novelist. But Frank O’Connor, in The Lonely Voice: A Study of Short Fiction, cites him along with A.E.Coppard as one of the two best English storytellers.

Lawrence’s published output of short stories runs to three volumes. He was also a travel writer and essayist, and I even have an introduction by him to a Foreign Legion memoir. His travels, and his education, which enabled him to escape the nets of class, country and culture, meant that his writing has a much wider sense of experience than one might expect from the child of a mining community.

‘Odour of Chrysanthemums’ goes right back to his childhood and is firmly rooted in the narrow confines of a pit village. Although the narrative voice is in standard English, the characters express themselves in broad Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire Coalfield. I grew up a few miles from that language, but it was as alien to me as Martian.

However, it is not so much the language, but the use of language that excites me. The story opens with colliery Locomotive Number Four – ‘with seven full wagons’ – and we travel with it through fields ‘dreary and forsaken’, past ‘a reedy pit-pond’ to the ‘harbour’ of sidings at Brinsley Colliery. Here, we find miners, ‘single, trailing and in groups’, going home in the early evening, while the wheels of the pit’s winding engines spin ‘fast against the sky’.

However, it is not so much the language, but the use of language that excites me. The story opens with colliery Locomotive Number Four – ‘with seven full wagons’ – and we travel with it through fields ‘dreary and forsaken’, past ‘a reedy pit-pond’ to the ‘harbour’ of sidings at Brinsley Colliery. Here, we find miners, ‘single, trailing and in groups’, going home in the early evening, while the wheels of the pit’s winding engines spin ‘fast against the sky’.

A page and a half of description precedes the introduction of the main character, who is not named to us for another two pages, but is introduced as ‘a woman’ whose ‘face was calm and set, her mouth was closed with disillusionment’. Our arrival at that last word, ‘disillusionment’, is like the collapse of a pit-face. It is full of human power and feeling; the descriptions before, of ‘forsaken’ fields, do not match it, nor do the ‘red sores’ of the flames flickering on the sides of the pit-bank. ‘Disillusionment’ is not merely a place, or a state of being, but lies at the end of a trajectory – a movement, through experience, from ‘illusion’ or ‘delusion’ to a grim truth.

Lawrence builds his picture slowly and surely. The woman calls in her young boy and brings him home as the afternoon darkens to dusk. A steam engine, driven by her father, stops at the house and she offers tea. All is not well between them and her father apologises for not visiting.

“I didn’t expect you,” said his daughter coldly.

The engine driver winced.

Their brief conversation reveals his intending marriage, but, more importantly, it reveals that the woman’s husband is turning into a drinker. As the engine passes on, ‘darkness was settling over the spaces’ and, by now, even before we learn the woman’s name, Lawrence has shown us that darkness is settling over this entire story.

There are several issues around the use of names in this story, or, more accurately, around the labelling of characters. By the time we meet this woman, calling in her son, we have already glimpsed ‘a woman’ beside the railway. Yet, from the context, we know that this second mention of ‘a woman’ signifies a main character. It is curious, though, that two should be introduced with the same phrase. Perhaps little anomalies like this serve to draw our attention, to raise our awareness, and make us read more carefully. That second ‘woman’, who calls in her son, becomes Elizabeth Bates, but she is not always addressed as such. By turns she is ‘the daughter’, ‘the mother’, and ‘the wife’. To her mother-in-law she is Lizzie and, as the story progresses, she becomes simply Elizabeth to the reader. The way she is addressed in each instance affects the way we perceive her.

Walter Bates, whose forename is used only once, is similarly called by many names. ‘The man’ is common, with added ‘dead’ and ‘helpless’. Annie calls him ‘my father’, Elizabeth, ‘your father’. Often he is ‘the husband’. In a story in which half a dozen minor characters are given names, we cannot ignore how the two main characters are named, and not named.

As the evening wears on and the darkness deepens, and her husband does not return, Elizabeth’s anger that he might have gone to the public house is eclipsed by her fear that he may not have come out of the pit. Lawrence splits his story into two, and it is at this turning point that he makes that split: ‘Meantime her anger was tinged with fear.’

In fact, Elizabeth’s husband has been suffocated after a fall of rock has cut off his exit route. His mother has joined Elizabeth in the cottage. Neighbours have searched for the missing man. Then, eventually, his body is carried home, perfect and untouched, by other colliers. From her angry assertion – ‘I won’t wash him’ – earlier in the evening, Elizabeth has moved to ‘I must wash him’, as he lies on the parlour floor.

In fact, Elizabeth’s husband has been suffocated after a fall of rock has cut off his exit route. His mother has joined Elizabeth in the cottage. Neighbours have searched for the missing man. Then, eventually, his body is carried home, perfect and untouched, by other colliers. From her angry assertion – ‘I won’t wash him’ – earlier in the evening, Elizabeth has moved to ‘I must wash him’, as he lies on the parlour floor.

It is not the revelation of his death, or of her misapplied accusations, that stand as the point of this dark story. Instead, it is the revelation, as Elizabeth and her mother-in-law lay out his corpse, that the relationship between husband and wife has been itself an illusion. The last pages of the story show us her mental examination of this truth.

Here is a story with a strong ‘arc’. An arc not only of events, but of focus, intensity, and language. For as Lawrence moves us towards his denouement, there is a shift in what he is writing about. What began as a naturalistic description of a particular place and time, has turned into the thoughts of a single woman in a small dark room as she lays out her husband’s body. That first striking word, ‘disillusionment’, has been stripped bare as the miner’s corpse, for her and for us.

Early in the story, the room has darkened, even though the fire is lit and lamps are lighted. As Elizabeth now adds coal to the fire, ‘the shadows fell on the walls, till the room was almost in total darkness’. Coal has snuffed out this light too.

The physical background to the story – the pit village, the brook, the fields, and the colliery itself – have all been overwhelmed by darkness, as if all the light had been gathered together into the body of the miner:

“White as milk he is, clear as a twelve-month baby, bless him, the darling!” the old mother murmured to herself. “Not a mark on him, clear and clean and white, beautiful as ever a child was made.”

Just as Walter Bates has been overwhelmed by darkness in the pit, and brought out as a form of light, so a darkness has overwhelmed the mining village. But in this darkness, Elizabeth has seen the light – about her relationship with her husband and about her own life.

This story is over one hundred years old, first published in 1911, in English Review. The actual world in which it is set, both time and place, is long gone. Its themes, though, are universal; life and death pervade all time and all place, and will continue to do so.