photo by Steve Slater

by Neil Campbell

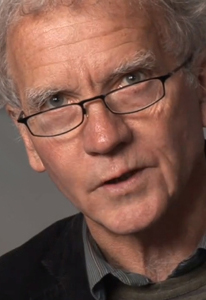

I saw David Constantine reading at Manchester Cathedral a few years ago. He could have been a vicar standing there with his unruly grey hair and measured incantatory voice. I was younger then, and much of the subtlety of Constantine’s story was lost on me. I’ve had to learn how to listen to stories.

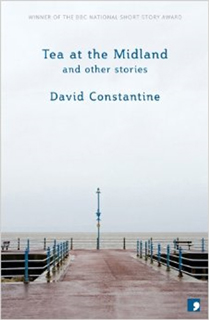

It was while listening to the radio that I first heard part of ‘Mr Carlton’, Constantine’s story about a recently widowed man stuck by the side of a motorway after an accident further up the road. I had switched on the radio at the moment in the story when a herd of fallow deer emerge from under a bridge. It was a moment of amazement with which I could identify, having seen fallow deer during walks. The promise of this single image kept me listening. I felt like I was being ushered gently into a dream. More recently, I heard the full story prompting me to buy Tea at the Midland and Other Stories.

Many of Constantine’s stories are as gentle as the man himself appeared to be on the day I saw him reading (although the humour in a story like ‘Goat’ shows a different side). ‘Mr Carlton’ is one of his shorter efforts, but if I finish a story and it stays with me, then that is a great story. If my mind holds images from the story beyond the story’s end then, like poetry, it helps me feel more human and less apart from the world.

Many of Constantine’s stories are as gentle as the man himself appeared to be on the day I saw him reading (although the humour in a story like ‘Goat’ shows a different side). ‘Mr Carlton’ is one of his shorter efforts, but if I finish a story and it stays with me, then that is a great story. If my mind holds images from the story beyond the story’s end then, like poetry, it helps me feel more human and less apart from the world.

My favourite stories are almost always more like poems than novels. John Cheever’s prose is always couched in poetry and ‘The Swimmer’ is arguably one of the greatest short stories ever written. The final few pages of Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ are also closer to poetry than prose. The best stories, like the best poems, are just too good to be broken down and completely understood. Constantine’s stories capture what Flannery O’Connor called the ‘mystery of existence’. Posed questions, not answers; verisimilitude, not plot. I’ve always enjoyed the absence of plot in his stories and how, in that sense, they subvert the advice often given to beginning writers.

In a recent interview on The Short Review, Constantine said:

A story, for me, is a fiction in which something is under way, at work, at stake; in which possibilities for good or ill are opening up. I write against the very idea of finality and closure.

In an essay on D.H. Lawrence, from the Comma anthology Morphologies, Constantine writes that, ‘such writing cannot even desire to arrive at a fixed point. It arrives at something tentative, provisional, opening. There is no closure in Lawrence’s writing because there is none in life’.

I have always preferred what might be described as ‘open endings’. In ‘Mr Carlton’ the story finally arrives at precisely the kind of ‘tentative, provisional, opening’ that Constantine describes in his essay on Lawrence – when the accident has cleared and the cars start moving again…

Now we’ll be moving soon, said Mr Carlton. Do you want to go back to your car? I’ll stay here, if you don’t mind, until it starts, said the young woman still gripping Mr Carlton’s arm.

Where one story ends, another story could easily start. To me, this seems more true to life than a neat conclusion. As Constantine’s fiction editor Ra Page writes in his introduction to Morphologies:

With a short story, the meaning of the ending is projected in both directions, backwards (illuminating an unseen plot or a misread character) as well as forwards, into the surviving future.

What happens to Mr Carlton and the girl at the end of the story? What happened before the start of the story? Pondering these questions adds to the reader’s pleasure. Finding the right balance is the thing. Leave too much out and all potential for suggested meaning is lost. Short story writers are dependent on collaborative readers.

I have my own thoughts as regards meaning in ‘Mr Carlton’, but they aren’t as important to me as the feeling of being immersed in a dream while reading it. The story starts after a cremation, and Mr Carlton drives down the motorway afterwards feeling ‘vulnerable as a snail among marching men in boots’, a wonderfully congruent simile. The metaphor of the accident along the road is that of life stopping in full flow, forcing people to pause, and this is suggestive of the lives of all the people in the story. For Mr Carlton this means he can observe and look beyond himself, whether that is at the fallow deer emerging from under the motorway, or the water pouring from the watering can of the man gardening outside his house, or swallows, or a blackbird on a roof:

The swallows came and went, at speed, intently, with a clean skill and grace. A blackbird sang from the apex of the roof. Was it so or similar, changing with the seasons but in essence just so, all fitting, all in place, all pleasing, was it always so even under the usual traffic?

The contemplation of those moments helps our humanity, and it helps Mr Carlton, provides solace. Constantine, like Hemingway before him, has a naturalist’s eye for observed detail.

The contemplation of those moments helps our humanity, and it helps Mr Carlton, provides solace. Constantine, like Hemingway before him, has a naturalist’s eye for observed detail.

By the side of a motorway, raised up, ‘over a flat moss whose chief beauty was once of birch woods’, Mr Carlton sees that although things have changed, there is still beauty to be found from ‘all those creatures that have come out from under the motorway’. For Mr Carlton, so recently bereaved, there is also the ‘great joy’ of his grandchildren. In that sense, the story has a classic moment of realisation, though it is depicted so subtly that Constantine avoids any danger of cliché. ‘The after-lingerings of a midsummer sunset last for ever. Infinitely slowly, pallor passes towards blackness. The vanishing light edges north, smoulders on earth long after the source of it has gone below.’

When I read ‘Mr Carlton’, it was at a time when I needed the story; it gave me solace by showing me the difficulties faced by someone else. It also reminded me of the myriad pleasures to be found in the natural world. We should all sit and watch the world more closely, or walk through it slowly and savour it, waiting, like Mr Carlton, for the creatures that ‘come out from under the motorway’.