photo by eltpics

We are delighted to announce the results of the

2013 THRESHOLDS International Short Story Feature Writing Competition.

Our 2013 winner is: Nuala Ní Chonchúir

Runner-up: Dan Powell

(Look out for Dan Powell’s feature on The Forum on Monday 29 April.)

*

Comments from the judging panel

for ‘A Trio of Irish Short Stories’:

‘A rich, deft piece about the way we are each inhabited by stories’; ‘the piece charms with its wonderfully lively and engaging voice’; ‘she takes a unique approach to the Competition brief’; ‘the writing illuminates not only the stories discussed but, intriguingly and evocatively, the writer herself – showing how stories touch us as people and influence us as writers’; ‘a fluent and stylish analysis of how stories that are read at a certain age stay with us forever’.

*

A Trio of Irish Short Stories

by Nuala Ní Chonchúir

When I first became serious about writing, I resisted the notion of influence. I knew the writers I admired and aspired to be as good as, but I was hesitant to acknowledge them as influential. Fast forward through years of writing and several published books, and I am as grateful as it is possible to be to those who influenced me. I realised, at some point, that influence is crucial to a developing writer. To every writer.

I know who has influenced me, among them Edna O’Brien, Éilís Ní Dhuibhne, Mary Morrissy, John McGahern, Valerie Trueblood, Anne Enright, Annie Proulx, Michele Roberts, James Joyce, Sharon Olds, Michael Hartnett and many others. These are people I remember reading as a writer and marvelling at for many aspects of their work. But I have been wondering, too, about stories read when I was young, and how they influenced me without my knowing.

There are three Irish short stories I remember reading in particular. Amongst all the stories I read as a child, it is this trio of fictions that became a part of me. Something in each sang to the young me, the girl who was writing stories and poems because they helped me somehow, though I would not have said that then.

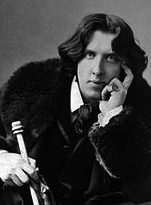

So, what made me weave Seán Ó Faoláin’s story ‘The Trout’ into my own mythology? What was it about Brendan Behan’s ‘The Confirmation Suit’ that spoke to me so truly? And why did Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Happy Prince’ fill me with an unnameable longing?

Ó Faoláin’s ‘The Trout’ concerns Julia, a little girl who finds a ‘panting’ trout in a secluded well and sets out to rescue it. The landscape of the story is an old laurel walk, ‘a lofty midnight tunnel of smooth, sinewy branches’, and is similar to a place near my home in County Dublin (my sisters and I called this place the ‘Sleeping Beauty passage’). I must have been about eleven or twelve years old when I first read ‘The Trout’, but at some point I wove this story into my own memories and thought that I was the girl – so much so that, when I re-read ‘The Trout’ as an adult, it felt like I was reading my own history.

Ó Faoláin’s ‘The Trout’ concerns Julia, a little girl who finds a ‘panting’ trout in a secluded well and sets out to rescue it. The landscape of the story is an old laurel walk, ‘a lofty midnight tunnel of smooth, sinewy branches’, and is similar to a place near my home in County Dublin (my sisters and I called this place the ‘Sleeping Beauty passage’). I must have been about eleven or twelve years old when I first read ‘The Trout’, but at some point I wove this story into my own memories and thought that I was the girl – so much so that, when I re-read ‘The Trout’ as an adult, it felt like I was reading my own history.

Twelve is a momentous age: it signals the cusp of adolescence, the move away from childhood towards the teens. The girl in ‘The Trout’ is twelve. Her name – Julia – is not far from my own name, pronunciation-wise; her ‘lofty midnight tunnel’ was my Sleeping Beauty passage. I became her and I would have put my hand on my heart and told anyone that it was I, in fact, who had found a trout in a well. But there was no well in the Sleeping Beauty passage near my home, so how does my co-opting memory account for that? Presumably the landscape of the story, so like my childhood landscape, tricked me into believing Julia was me. Whatever happened, that story stayed with me in a profound way. ‘…[Julia] came to the cool ooze of the river’s bank where the moon-mice on the water crept into her feet.’ That could so easily have been my twelve-year-old self on the oozing bank of the Liffey.

As a child, I was deeply moved by ‘The Happy Prince’, Oscar Wilde’s melancholic morality tale of an unlikely friendship. No doubt my parents read it to me before I read it for myself. The story unfolds when a maverick swallow meets a magnificent golden statue of a prince who, despite his beauty and riches, is unhappy. He asks the swallow to remove his gold leaf, sapphires and rubies to give to the poor. The swallow delays his migration to Egypt to help the prince and they become friends, but both, sadly, die in the doing of their good deeds.

As a child, I was deeply moved by ‘The Happy Prince’, Oscar Wilde’s melancholic morality tale of an unlikely friendship. No doubt my parents read it to me before I read it for myself. The story unfolds when a maverick swallow meets a magnificent golden statue of a prince who, despite his beauty and riches, is unhappy. He asks the swallow to remove his gold leaf, sapphires and rubies to give to the poor. The swallow delays his migration to Egypt to help the prince and they become friends, but both, sadly, die in the doing of their good deeds.

‘The Happy Prince’ has all the story elements that both child and adult require: striking language, recurring motifs, beautiful melancholy, a crescendo, and a definitive ending. Wilde’s story alerted me to the power of fiction, to its beauty and its ability to move the reader and make her think about other lives, other possibilities, other places. It is not recognisably Irish – its Irishness is of note only because an Irishman wrote it – and I was attracted to the story for its seeming exoticism. I liked, too, its almost stilted use of language and the fairytale narrative. The poignant tone was also a draw for a child fond of melancholic things. Happy endings were never a requirement with me:

“What a strange thing!” said the overseer of the workmen at the foundry. “This broken lead heart will not melt in the furnace. We must throw it away.” So they threw it on a dust-heap where the dead Swallow was also lying.

“Bring me the two most precious things in the city,” said God to one of His Angels; and the Angel brought Him the leaden heart and the dead bird.

“You have rightly chosen,” said God, “for in my garden of Paradise this little bird shall sing for evermore, and in my city of gold the Happy Prince shall praise me.”

Different in tone entirely is Brendan Behan’s ‘The Confirmation Suit’. It tells the story of a boy whose Confirmation suit is made by an old woman who mostly makes habits for the dead. The suit is not what the boy had hoped for – it has ‘little lapels and big buttons’. The narrative is from the child’s point of view, and is related in lively Dublin English. After the narrator’s disgust at the much anticipated suit, and after fooling the woman who fashioned it by putting it on for a few minutes each week to visit her, the ending of the story sees him try to make amends:

Different in tone entirely is Brendan Behan’s ‘The Confirmation Suit’. It tells the story of a boy whose Confirmation suit is made by an old woman who mostly makes habits for the dead. The suit is not what the boy had hoped for – it has ‘little lapels and big buttons’. The narrative is from the child’s point of view, and is related in lively Dublin English. After the narrator’s disgust at the much anticipated suit, and after fooling the woman who fashioned it by putting it on for a few minutes each week to visit her, the ending of the story sees him try to make amends:

After the funeral, I left my topcoat in the carriage and got out and walked in the spills of rain after her coffin. People said I would get my end, but I went on till we reached the graveside, and stood in my Confirmation suit drenched to the skin. I thought this was the least I could do.

As a youngster I loved that this was a funny story, told in the language of my home place, but that ultimately Behan was able to trick me by ending the story on a poignant note. This is the sort of surprise the reader hopes for from short fiction.

Each of these stories gave me, as a very young reader, what we look for in short fiction: that unique hit of urgency, wonder and concision. Each one is beautifully unpredictable, with a burning question at its heart. And each writer – Ó Faoláin, Behan and Wilde – spotlights the ending in a unique way. With their closing lines, they say to us, ‘This is the last thing I want you to see’ and that thing, in all three stories, is vital.

It’s good to see these stories through fresh eyes and look at them again.It is as if Nuala has taken them out and washed them, refreshing their colours. It shows how important stories can be, they stay with us through years -and are not dislodged.

Thank you, all at Thresholds, for the opportunity to submit. I am delighted that you chose my essay as the winner. I look forward to reading all the other essays.