('Teton Weather' © Scott Law, 2012)

BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN: MASCULINITY, ROMANCE, AND PERSPECTIVE

by CHRIS MACHELL

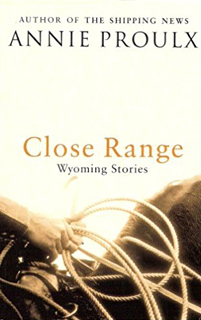

‘Brokeback Mountain’ is one of eleven short stories in Annie Proulx‘s 1999 collection, Close Range. Ang Lee’s 2005 adaptation of the story retells Proulx’s brief 28 pages across 128 minutes of screen time, yet rarely if ever feels padded. Lee’s film lost out to Paul Haggis’ now largely-forgotten Crash as that year’s Best Film Academy Award, as well as drawing some controversy from conservative media for its depiction of the same sex romance. Nevertheless, Brokeback Mountain was a critical and commercial success and remains among the director’s best films. Lee’s film is extremely faithful to its source text, yet its emphasis on certain aspects of the story creates interesting new dimensions and thematic tensions. This is especially true of the expansion of the women’s role in the film, and their influence on the story’s depiction of masculinity.

In Proulx’s story, Ennis and Jack meet on a summer job, tending sheep on the eponymous mountain. Over the course of weeks, they slowly bond, Ennis’ taciturn temperament softened by the more talkative Jack. Eventually, on a night spent sharing the same tent, ostensibly for warmth, their bond spills over into sexual desire, consummated in a frantic act. Proulx describes it in unvarnished detail:

Ennis ran full throttle on all roads whether fence mending or money spending, and he wanted none of it when Jack seized his left hand and brought it to his erect cock. Ennis jerked his hand away as though he’d touched fire, got to his knees, unbuckled his belt, shoved his pants down, hauled Jack onto all fours and, with the help of the clear slick and a little spit, entered him, nothing he’d done before but no instruction manual needed. They went at it in silence except for a few sharp intakes of breath and Jack’s choked “gun’s goin off”, then out, down, and asleep.

There’s little in the way of romance and despite their obvious desire, after the fact, both men continue to assert that they’re ‘not queer’. The equivalent scene in Lee’s film is depicted similarly to the Proulx’s text, but the context is subtly different. Proulx’s language emphasises the harshness of the men’s environment: ‘a thousand ewes and their lambs flowed up the trail like dirty water through the timber and out above the tree line into the great flowery meadows and coursing, endless wind’. Proulx’s describes the environment as a fundamentally masculine space where its value is measured in its utility rather than its beauty. In contrast, Lee’s visuals tend towards the romantic: sheep graze lazily on the side of the mountain and Ennis and Jack ride horseback while Gustavo’s Santaolalla’s lovely guitar-based score frames the environment with a sparse poetry. We see little of the ranch work in the film, and when we do, it is often as Ennis looks out reflectively across the twilight landscape. As a result, the hard masculinity of Proulx’s story is softened by Lee’s film.

There’s little in the way of romance and despite their obvious desire, after the fact, both men continue to assert that they’re ‘not queer’. The equivalent scene in Lee’s film is depicted similarly to the Proulx’s text, but the context is subtly different. Proulx’s language emphasises the harshness of the men’s environment: ‘a thousand ewes and their lambs flowed up the trail like dirty water through the timber and out above the tree line into the great flowery meadows and coursing, endless wind’. Proulx’s describes the environment as a fundamentally masculine space where its value is measured in its utility rather than its beauty. In contrast, Lee’s visuals tend towards the romantic: sheep graze lazily on the side of the mountain and Ennis and Jack ride horseback while Gustavo’s Santaolalla’s lovely guitar-based score frames the environment with a sparse poetry. We see little of the ranch work in the film, and when we do, it is often as Ennis looks out reflectively across the twilight landscape. As a result, the hard masculinity of Proulx’s story is softened by Lee’s film.

When Jack visits Ennis at his home years later, the scene plays out much the same in the film as it does in the story. Consumed by lust and years of longing, the men embrace in a passionate kiss, while Ennis’ wife, Alma, played by the inimitable Michelle Williams in the film, accidentally sees them through the screen door. However, where the films’ scene depicts the intensity of their feelings through Gyllenhaal and Ledger’s loving embrace, the book’s language is masculine, coarse, and violent:

They seized each other by the shoulders, hugged mightily, squeezing the breath out of each other, saying, son of a bitch, son of a bitch, then […] their mouths came together, and hard, Jack’s big teeth bringing blood […] stubble rasping […] pressing chest and groin and thigh and leg together, treading on each other’s toes.

Again, the environment is hyper-masculine – almost animalistic – with the growling thunder signalling Jack’s arrival. Later, the pair book a motel room, but where Lee shoots Ennis and Jack in a tender post-coital embrace, Proulx’s language is viscerally masculine and subtly fetishistic: ‘The room stank of semen and smoke and sweat and whiskey, of old carpet and sour hay, saddle leather, shit and cheap soap’. Where Lee’s film emphasises Jack’s sense of romantic idealism, Proulx’s language is hard, her characters taciturn extensions of their environment.

Lee’s subtle softening of Proulx’s masculine language is further reflected in his emphasis of the story’s female characters. Ennis’ wife is barely seen in the story, and save for some pointed references and a single phone call to her from Ennis, Jack’s wife, Lureen, is entirely absent from the story. In contrast, in Lee’s film Lureen is a full supporting character. Played by Anne Hathaway, her role in Brokeback Mountain arguably signalled her move towards being taken seriously as a dramatic actor. Her terse conversation with Ennis after Jack’s death speaks of betrayal, resentment, and ultimately, boredom. In both the film and the story, Jack tells Ennis that they could almost conduct their marriage over the phone, but it’s only in the film that we see this play out, her emotional detachment from Jack increasing with each passing year.

Lee’s increased emphasis on the women in the narrative doesn’t detract from Ennis and Jack’s story, but it does reframe it in an interesting way. In Lee’s film, we’re granted access to the consequences that their relationship has on the people around them. This is especially true of Alma and their daughters. In the short story, Alma sees Jack and Ennis kissing through the screen door, but it is only in the film that we are shown her reaction. This is not to say one is better than the other – Proulx’s fixation on Jack and Ennis’ perspective makes the later episode when Alma leaves a note in Ennis’ fishing tackle – confirming her suspicions – all the more emotive. Yet equally, the perspective shift the film affords us extends the emotional stakes beyond simply Ennis and Jack to their wives and children.

Lee’s increased emphasis on the women in the narrative doesn’t detract from Ennis and Jack’s story, but it does reframe it in an interesting way. In Lee’s film, we’re granted access to the consequences that their relationship has on the people around them. This is especially true of Alma and their daughters. In the short story, Alma sees Jack and Ennis kissing through the screen door, but it is only in the film that we are shown her reaction. This is not to say one is better than the other – Proulx’s fixation on Jack and Ennis’ perspective makes the later episode when Alma leaves a note in Ennis’ fishing tackle – confirming her suspicions – all the more emotive. Yet equally, the perspective shift the film affords us extends the emotional stakes beyond simply Ennis and Jack to their wives and children.

Similarly, the film’s scene with Jack and Lureen’s father carving the thanksgiving turkey is an expansion of an incident referred to in the short story, yet is crucial in depicting a rare moment of alpha masculinity for Jack. Much like seeing Alma’s devastation at Ennis’ secret, the scene where Jack tells Lureen’s patriarchal father that ‘this is my house […] and you are my guest’ recontextualises our perception of him. The assertion of his domestic masculinity is juxtaposed against his submissive role in his relationship with the hard-bitten Ennis. Indeed, this can be contrasted with the domesticity of the early days of his and Ennis’ relationship on Brokeback Mountain, where each take it in turn to ‘commute’ to work and tend the sheep while the other keeps the camp running and prepares the meals.

The hardness of Proulx’s text is softened by Lee’s more romantic, idealised camera lens, yet both versions feel as authentically emotive as the other. As much as the increased emphasis on the Lureen and Alma acts to recontextualise the narrative, it is almost as if the film has been partially given over to Jack’s softer vision of the world. Ennis’ mantra, ‘if you can’t fix it, you’ve got to stand it’, is the hard edge of Proulx’s story. Yet is an edge ever so slightly softened by Lee’s film, retaining the smallest morsel of Jack’s idealism.

~

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.

One thought on “Brokeback Mountain: Masculinity, Romance, and Perspective”

Comments are closed.