photo by o0o0xmods0o0o

by Jeanloup Pranchère

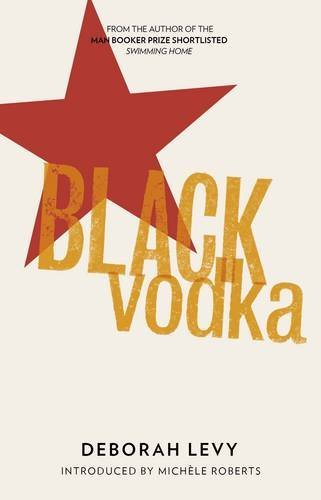

‘I have always thought of myself as lost property, someone waiting to be claimed,’ confesses the main character in the title story of Deborah Levy’s new collection, Black Vodka. In this, the opening story in the collection, we first encounter the powerful preoccupations that Levy will return to in the nine stories that follow. Throughout, in spare, poetic prose, she grapples with the complex and often mysterious nature of identity.

The story ‘Black Vodka’ focuses on Ali – the hunchback employee of a leading advertising agency – as he meets Lisa, a beautiful archaeologist who is fascinated by him. Lisa sees Ali as ‘an archaeological site’, and objectifies him under her scientific gaze, as if ‘staring through the lens of a microscope’. But Ali, like many characters in the collection, finds he is unable to express the complexity of who he is, or even the complexity of his surroundings: ‘there is so much of the world to record and classify, it’s hard to know how to find a language for it.’ Similarly, when the male character in ‘Vienna’ asks his one-night lover what her first language is, he is faced with a non-answer, one that conceals her true identity: “There are so many languages.”

Language, our most vital means of expression, is nevertheless too polymorphous, and at the same time too limited, to clearly draw the self. Its unreliability is evoked in ‘Pillow Talk’, in which the protagonists, all from multi-cultural backgrounds, dread their lack of words to prove their identity to an airport official: ‘What if he asks them to explain where they come from? What would you say? “A bit from here, a bit from there?”’

In Black Vodka, the idea of language is closely associated with place and setting. The stories cross national boundaries. We are offered Polish clubs, Dutch tutors, Czech tourists, and Japanese job interviewers in Dublin; the collection’s Europe-wide focus evokes a sense of universality. At the end of ‘A Better Way of Life’ – the most optimistic story in the collection, and the closing piece – two characters seal their marriage in a way that is reminiscent of the famous last words of Ulysses: ‘We said yes in all the European languages. Yes. We said yes we said yes, yes to vague but powerful things!’

Although her characters’ communication and language skills are often lacking, Levy invests them with vivid, insightful imaginations. And that phrase, ‘powerful things’, can certainly describe the intricate imagery crafted by Levy in her stories:

While he negotiated with the car salesman, it occurred to Simon that this man had a substantial volume of blood pumping through a purple vein in his forehead. The salesman (who wore a thick gold wedding ring on his finger) was pointing at the vintage Cadillac of Simon Tegala’s dreams. Mr Tegala the customer had suddenly become butcher. He saw the salesman merely as a sum of parts with blood flowing between, through and around them. A biological highway of organs, venules and veins.

These compelling evocations resound throughout the stories, giving the collection as a whole a strongly poetic quality –. We are asked to ‘imagine a butterfly displayed in a glass case suddenly flying towards you with the pin still in its body’. We are reminded that ‘silence is cruel in cities where missing people need to hide in noise’.

These compelling evocations resound throughout the stories, giving the collection as a whole a strongly poetic quality –. We are asked to ‘imagine a butterfly displayed in a glass case suddenly flying towards you with the pin still in its body’. We are reminded that ‘silence is cruel in cities where missing people need to hide in noise’.

Exquisitely crafted images are legion in Black Vodka. We are surprised by lethargic swans outside a health institution, a mysterious musician nicknamed ‘Mr Composer’, and pears that lie like naked, dead animals on silver trays. Images such as these create a symbolic framework that binds the stories and endows them with their ‘depth-charge’ power, as Michele Roberts notes in her introduction to the collection.

Notably, telephones feature throughout the collection as everyday symbols for connectedness. In ‘Black Vodka’, Ali realises ‘Lisa actually pressed the digits that connected her to [his] voice’. In ‘Placing a Call’, a bird imitating a phone signifies the illusion of being connected. And, most significantly, in ‘Shining a Light’, Alice, a British tourist whose luggage has gone missing – leaving her without a phone charger – meets Alex, a Serbian man who happens to have the same phone as her. The phone acts as a tie between them, as it brings them closer, in spite of their differing cultures. The story ends with Alex offering ‘to charge up her mobile phone for her before she leaves for London’, thus restoring her link with her home, a connection that he himself has lost. In this collection, the mere act of using a phone is transformed into a much more significant act – that of a bond between two people. Levy uses the resonant power of images to convey profound meaning via the seemingly mundane.

There is a dynamic opposition that runs throughout the stories, a narrative tension arising from the confrontations between the inner lives of the characters and the outer worlds they inhabit. In ‘A Better Way to Live’, this is deftly expressed: ‘although our interior worlds are volcanic, exotic, troubled, the everyday is beautifully predictable.’ In ‘Vienna’, the main character’s guilt — the result of abandoning his family — is figured by a physical manifestation: ‘the rash on his hands is the memory of saying goodbye to his small children when he left the family house, knowing he was never going to return.’ The rash — which he has in common with several characters in the collection — is the literal outbreak of his inner life:

He thinks about how there is life with rye bread and black tea and there is life with champagne and wild salmon. He can live without champagne but he cannot live without his children; that is a grief he knows he cannot endure but he must endure and he knows his hands will itch for ever.

After Levy’s Man Booker Prize-shortlisted novel Swimming Pool, it does not come as a surprise that water should be one of the most recurring motifs in Black Vodka. Rain, drinking, lakes, rivers, moats… water pervades every story. Ali in ‘Black Vodka’ is exhilarated by the rain:

There’s something about rain that makes me slam the doors of cabs extra hard. I love the rain. It heightens every gesture, injects it with 5ml of unspecific yearning.

In ‘Shining a Light’, the luggage belt from which Alice’s bag is missing is compared to a ‘dead grey river’. The image returns when when she arrives at a lake that used to be a cave: ‘it might have some sort of force that will suck her deep into the earth and make her disappear like her lost suitcase.’ In ‘Pillow Talk’, the voice of a man, confessing to his lover that he has betrayed her, sounds like ‘he’s drowning’. More significant still is the protagonist of ‘Cave Girl’. He is troubled by his sister who, having undergone plastic surgery, speaks ‘like she’s trailing the tips of her fingers across the surface of a swimming pool’. The boy, scared of ‘things lurking in the sea’, is ultimately worried that below the surface of this ‘pretend woman’, lies his sister’s old self, waiting to suddenly jump out. The complexity and elusiveness of identity is figured through recurring images of water, the ever-changing element that can be both shallow and deep, still and shifting, clear and cloudy, all at once.

In ‘Shining a Light’, the luggage belt from which Alice’s bag is missing is compared to a ‘dead grey river’. The image returns when when she arrives at a lake that used to be a cave: ‘it might have some sort of force that will suck her deep into the earth and make her disappear like her lost suitcase.’ In ‘Pillow Talk’, the voice of a man, confessing to his lover that he has betrayed her, sounds like ‘he’s drowning’. More significant still is the protagonist of ‘Cave Girl’. He is troubled by his sister who, having undergone plastic surgery, speaks ‘like she’s trailing the tips of her fingers across the surface of a swimming pool’. The boy, scared of ‘things lurking in the sea’, is ultimately worried that below the surface of this ‘pretend woman’, lies his sister’s old self, waiting to suddenly jump out. The complexity and elusiveness of identity is figured through recurring images of water, the ever-changing element that can be both shallow and deep, still and shifting, clear and cloudy, all at once.

A sense of history is also vital to Levy’s reflections on identity; it pours through the surroundings of the characters. They realise that ‘under the twenty-first century paving stones there had once been fields and market gardens’, and they think about ‘the twentieth-century that ended at the same time as [their] marriage’. This correspondence between history and identity is nostalgically expressed by the young narrator of ‘A Better Way to Live’, whose mother was a historian:

The Fall of the British Empire, I associate with brown shoe polish and Mom’s high heels, while Fidel Castro’s army taking power in Cuba is irrevocably linked with the warm maple syrup she poured onto pancakes on Sunday mornings. My mother wanted a better life for Russian women selling their slippers in the Moscow snow and she wanted a better life for me, her London boy with bright eyes just like hers.

Black Vodka is a short but intense collection. In spite of the weight of its ideas and issues, it is never heavy, pretentious or confused. Levy has produced ten tales of loss and displacement, ten haunting contemporary fables that, like their characters, belong both to our time and to history, both to Europe and beyond.