('Marigold Garland' © momo, 2011)

BETRAYAL AND OTHER ACTS OF SUBVERSION: FEMINIST THEMES IN ‘THE LIMPING BRIDE’

By

ELEANOR WALSH

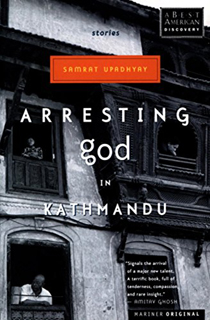

Samrat Upadhyay‘s ‘The Limping Bride’ can be found in his 2001 short story collection Arresting God in Kathmandu and in the 2002 anthology of English Literature from Nepal An Other Voice.

Nepali authors who write in English often come to represent a certain political allegiance in their writing. Upadhyay is no different; he is known mostly for stories that expose corruption and power imbalance; stories of Nepali citizens trying to find opportunity in a country that is struggling to progress. Although Upadhyay isn’t known for writing which is driven by conspicuous feminist themes, he writes female characters that are deeply complex and well-rounded; a far-cry from the subservient, obedient women who are so often silent on the side-lines of Nepalese literature.

Upadhyay’s story ‘The Limping Bride’ is no exception. It narrates the tale of a family in modern-day Kathmandu, and details the experiences of a widower, Hiralal, who struggles to take control of his household following the premature death of his wife, Rammaya, and the subsequent unpredictable and reckless behaviour of his alcoholic son, Moti. Hiralal attempts to curb Moti’s behaviour by arranging his marriage with Rukmini, who has a reputation as a beautiful and well-behaved girl. The only drawback, Hiralal is told, is that Rukmini is a langadi: she was born with a disability that causes her to walk with a limp. Upon discovering his new wife’s impairment on their wedding night, Moti treats Rukmini terribly, leaving her to bond only with Hiralal, who feels sympathy for the girl and her miserable new life in his home. However, just as Moti comes around and accepts Rukmini as his wife, Hiralal discovers that Rukmini’s nature is less pure and docile than the family were promised.

Any story centred on arranged marriage lends itself to analysis through a feminist lens. Certainly, it would not be difficult to write a harrowing story of a girl with an undisclosed impairment as she attempts to negotiate a new marriage with an alcoholic husband. And yet, thematically speaking, ‘The Limping Bride’ is not the story about arranged marriage we might expect. The narrative traverses all obvious pitfalls that might occur in any arranged marriage that could likely lead to the abuse of a new bride. Both families in the story seem well off. There is no mention of dowry exchange. If Rukmini had been reluctant to marry Moti, or expressed some wish to leave her martial household once Moti rejected her, or if Moti or Hiralal had raised a hand or even their voice to Rukmini, then we would be reading a story about the feminist issues that surround arranged marriages. Matters such as dowry-based and domestic violence, or coercion into marriage, tend to loom so large in a story that they obscure all other themes. Upadhyay is a writer who doesn’t take his reader for granted. He believes in an audience that pays attention. He evades the cookie-cutter predictability of the victimised-wife fable, and by doing so makes room for more nuanced feminist themes to quietly grow beneath a surface of apparent domestic harmony. In short, these characters are complex; they are victims and perpetrators; they at once suffer and cause suffering.

Any story centred on arranged marriage lends itself to analysis through a feminist lens. Certainly, it would not be difficult to write a harrowing story of a girl with an undisclosed impairment as she attempts to negotiate a new marriage with an alcoholic husband. And yet, thematically speaking, ‘The Limping Bride’ is not the story about arranged marriage we might expect. The narrative traverses all obvious pitfalls that might occur in any arranged marriage that could likely lead to the abuse of a new bride. Both families in the story seem well off. There is no mention of dowry exchange. If Rukmini had been reluctant to marry Moti, or expressed some wish to leave her martial household once Moti rejected her, or if Moti or Hiralal had raised a hand or even their voice to Rukmini, then we would be reading a story about the feminist issues that surround arranged marriages. Matters such as dowry-based and domestic violence, or coercion into marriage, tend to loom so large in a story that they obscure all other themes. Upadhyay is a writer who doesn’t take his reader for granted. He believes in an audience that pays attention. He evades the cookie-cutter predictability of the victimised-wife fable, and by doing so makes room for more nuanced feminist themes to quietly grow beneath a surface of apparent domestic harmony. In short, these characters are complex; they are victims and perpetrators; they at once suffer and cause suffering.

The most striking tension in the story is the stark disparity between what we, as the reader, learn about Rukmini’s character, and the other characters’ perception of her. The only words used to describe her are ‘good’ and ‘beautiful’. These words are reiterated so many times, that Rukmini is a ‘good girl’, and this inadequate summary of her being reflects a lack of understanding of the complexity of adult humans on the part of the characters that describe her that way – no person can exist as nothing more than a good, beautiful girl. And more than this, Rukmini has grown up in an environment where a fundamental part of who she is has been kept secret. She lives with a disability, and yet she has been taught from an early age how to disguise her condition. Her understanding of how to negotiate the world has been shaped within the confines of normalised secrecy and deceit. The confines of these rules seem to have worked – Moti doesn’t hear anything of Rukmini’s secret before his wedding day. Rukmini embodies secrecy. Societal restrictions have unwittingly cultivated her into an expert of masquerades. She has spent her life pleasing, posturing and submitting to men.

It’s reiterated by each character that Rukmini is the ‘good girl’, and yet when she makes a pass at her own father-in-law, she exhibits the kind of sexual assurance one could never expect from someone who had only just lost their virginity to their husband. Earlier, when she was left alone with Moti during their first meeting, she flustered him, though it’s never made clear exactly how. Cracks appear in the exterior of her ‘good girl’ pretence. Not only does Rukmini seem prepared to jeopardise her new marriage just as Moti begins to treat her as a wife, she also hides her infidelity with ease and grows frustrated when Hiralal’s conscience takes over and he struggles to act as normal in Moti’s presence. Moreover, the cause of her prompted unfaithfulness seems to be part of an attempt to not be asked to ‘give’ any more – she tries to bargain with Hiralal that he can no longer ask anything of her. Hiralal’s demands on Rukmini have been no more challenging than the burdens placed on any new wife – he has simply asked that she take care of his son and provide him with grandchildren. Yet, it seems, Rukmini was quietly desperate for escape.

There is something in the unresolved ending of the story that suggests that this tale is ultimately, in fact, about Rammaya, and by extension, many domestic Nepali women. The story can end as it does because the impending potential breakdown of Moti’s marriage and Hiralal’s family is immaterial, as the family had never recovered from their loss of Hiralal’s wife. Such is the case with so many families where the men are taken care of by the women – the domestic harmony of the family relied on Rammaya utterly; as the only woman in the house, she was the glue that held them all together. Their grief is not only unreconciled and unmanaged, but even after all these years their bereavement still feels as though it is in its early stages – Moti having succumbed to alcoholism and an unreasonable anger towards his mother for her untimely passing; Hiralal as he wanders forlornly after his new daughter-in-law, hoping that he might catch the scent of coconut oil in her hair that reminded him of his late wife. As unreasonable as the demands that are placed on Rukmini are, they were also every bit as unrealistic as the ones that were once faced by Rammaya. The story’s conclusion seems to be the crux of any fourth-wave feminist story: when women are treated as inferior, men also suffer terribly. Hiralal and Moti’s loss seems irreparable after the death of Rammaya, and their lives are just as quickly up-ended by Rukmini. By keeping women in the home, and by forcing them to remain domestic, uneducated and family-oriented, society leaves families vulnerable to irreparable fractures when (for whatever reason) the women in the family cannot meet the expectations placed solely on their shoulders.

There is something in the unresolved ending of the story that suggests that this tale is ultimately, in fact, about Rammaya, and by extension, many domestic Nepali women. The story can end as it does because the impending potential breakdown of Moti’s marriage and Hiralal’s family is immaterial, as the family had never recovered from their loss of Hiralal’s wife. Such is the case with so many families where the men are taken care of by the women – the domestic harmony of the family relied on Rammaya utterly; as the only woman in the house, she was the glue that held them all together. Their grief is not only unreconciled and unmanaged, but even after all these years their bereavement still feels as though it is in its early stages – Moti having succumbed to alcoholism and an unreasonable anger towards his mother for her untimely passing; Hiralal as he wanders forlornly after his new daughter-in-law, hoping that he might catch the scent of coconut oil in her hair that reminded him of his late wife. As unreasonable as the demands that are placed on Rukmini are, they were also every bit as unrealistic as the ones that were once faced by Rammaya. The story’s conclusion seems to be the crux of any fourth-wave feminist story: when women are treated as inferior, men also suffer terribly. Hiralal and Moti’s loss seems irreparable after the death of Rammaya, and their lives are just as quickly up-ended by Rukmini. By keeping women in the home, and by forcing them to remain domestic, uneducated and family-oriented, society leaves families vulnerable to irreparable fractures when (for whatever reason) the women in the family cannot meet the expectations placed solely on their shoulders.

The story calls on the reader to examine the expectations made of women in the absence of any overt suffering or oppression – without any obvious, urgent need for change. He sheds light on what can happen when we raise girls who can’t earn money and find financial independence, as well as when we raise boys unprepared in taking care of their own household and children, emotionally flogged out of their innate empathetic instincts and forced into the uncomfortable structure of manhood. Moreover, if society continues to shoehorn women into roles so overly simplified they cease altogether to be human, society will also be forced to deal with the subsequent social fallout and family breakdowns when women are taught to function within the boundaries of deception and duplicity.

Upadhyay doesn’t lead the feminist movement in Nepal, but his writing is certainly part of this stylistic evolution. He writes as a part of the influx of new writing that recognises the need for a counterpoise to the way women are represented in Nepali literature. ‘The Limping Bride’ is part of a new trend of literature that moves away from a tradition where women are axiomatically stripped of signifiers of individual agency, and away from female characters that are limited to passive, supporting roles in fiction. It is an accomplished and encouraging story within a literary development that refuses to continue to reduce women to the characteristics of their servitude, thereby allowing them as individuals and us as a society to continue to grow.

~

Eleanor Walsh is currently at Plymouth University completing a PhD in contemporary women’s poetry from Nepal. She also writes a monthly creative column ‘Rumours from the Hati Sar’ for the journal Coldnoon Travel Poetics. She spends much of her time in small villages in the lowlands of Nepal, researching literary tradition and letting her dog drink from her teacup.

Eleanor Walsh is currently at Plymouth University completing a PhD in contemporary women’s poetry from Nepal. She also writes a monthly creative column ‘Rumours from the Hati Sar’ for the journal Coldnoon Travel Poetics. She spends much of her time in small villages in the lowlands of Nepal, researching literary tradition and letting her dog drink from her teacup.