('The 13th Day is Always the Hardest' © DeeAshley, 2014)

*

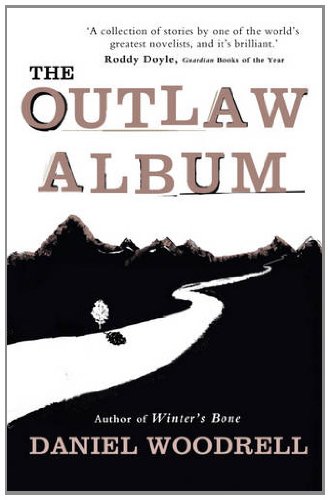

In this essay, shortlisted for the 2017 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Sean Baker finds the ‘country noir’ in Daniel Woodrell’s collection The Outlaw Album.

~

Comments from the judging panel:

‘I was gripped by this introduction to Woodrell’s work. The author of the piece shines an irresistible light on Woodrell’s stories, allowing us to see the elemental qualities, damaged characters and stark human truths that define it. We are offered tantalising glimpses of Woodrell’s landscapes, as well as an intriguing sense of a body of work – his short fiction – written, almost subversively, at some imaginative edge. A compelling read.’

‘This feature is sensitive not only to the themes of the work, but to the language it is written in too.’

‘Very fluently written … in a lively, perceptive way.’

~

Sean Baker is a PhD student at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. He is writing his first collection of stories, all set in the fenland villages north of Cambridge and is researching regionalism in the 21st century short story collection. In the past twelve months his stories have been listed for prizes from Bare Fiction, Stephen King/Guardian, Fiction Desk, Fiction Factory and theshortstory.co.uk. Since 2015 he has also won several ‘Best New Play’ awards at various drama festivals and is published by Off The Wall Plays.

Sean Baker is a PhD student at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. He is writing his first collection of stories, all set in the fenland villages north of Cambridge and is researching regionalism in the 21st century short story collection. In the past twelve months his stories have been listed for prizes from Bare Fiction, Stephen King/Guardian, Fiction Desk, Fiction Factory and theshortstory.co.uk. Since 2015 he has also won several ‘Best New Play’ awards at various drama festivals and is published by Off The Wall Plays.

~

~

BEINGS CHARGED WITH VIOLENCE

by SEAN BAKER

Daniel Woodrell could be said to be America’s best-kept secret, its greatest writer no one has ever heard of. Tell anyone that your favourite writer is Daniel Woodrell, and you are met with a blank face. I told an American tutor in creative writing at ARU last year that he was America’s greatest living writer and she said, “that’s a pretty bold claim, mister”. Even bolder given that she had never heard of him, either. But mention Winter’s Bone to most people and you get an “Ohhhh” of recognition as they recall the 2010 Oscar-nominated film starring Jennifer Lawrence pre-Hunger Games mega-fame. Point out that it’s actually based on a Daniel Woodrell novel of the same name and their faces register something approaching interest and a promise to check out the book.

The first writing of Woodrell’s I read was The Outlaw Album, his 2011 short story collection. It’s the perfect introduction to the work of this modern regionalist. The opening paragraph of the opening story – ‘The Echo of Neighborly Bones’ – is a pristine summation of everything you need to understand his style:

Once Boshell finally killed his neighbor he couldn’t seem to quit killing him. He killed him again whenever he felt unloved or blue or simply had empty hours facing him. The first time he killed the man, Jepperson, an opinionated foreigner from Minnesota, he kept to simple Ozark tradition and used a squirrel rifle, bullet to the heart, classic and effective, though there were spasms of the limbs and even a lunge of big old Jepperson’s body that seemed like he was about to take a step, flee, but he died in stride and collapsed against a fence post. Boshell took the body to the woods on his deer scooter and piled heavy rocks on the man, trying to keep nature back from the flesh, the parts of nature that have teeth or beaks.

In this paragraph you understand his world and his style. Ironic, matter-of-fact, blackly comic, rooted in the Ozarks of Missouri; full of rural concerns and references, the story is as good an introduction as you could wish for. The economy of his prose is there in the first phrase and the use of the word ‘finally’. You already know that this is something that was brewing awhile, that there was an inevitability to it. And two sentences later you learn everything you need to learn about both Boshell’s world and Jepperson’s fatal characteristic: he’s an ‘opinionated foreigner’. But not a foreigner from a foreign land – to Boshell, Minnesota is foreign. Boshell follows ‘simple Ozark tradition’ and three sentences in we already have so much stark detail with not a wasted word in sight.

And Jepperson’s mistake? He shot Boshell’s wife’s dog, Bitsy, who had been preying on Jepperson’s guinea fowl. In Boshell’s world this represents a crime: “That ain’t the neighbourly way, mister.” To Boshell it’s an eye for a dog’s eye, a tooth for a dog’s tooth. And in Woodrell’s prose, the dog’s death is desperate, sad, slow, painful, devastating:

Bitsy had crawled home hurt and collapsed beneath the split tree, gutshot, vomiting, looking up at Ev with baffled, resigned eyes, and it took two hours for her to bleed out and die with a last windy sound and a little flutter.

If the first story is dark, the second, ‘Uncle’, is darker still. The first sentence is short and, we soon learn, disarming in its apparent benevolence: ‘A cradle won’t hold my baby.’ The ‘baby’ in question is a two-hundred-pound serial sexual abuser and rapist of young girls and women – the ‘Uncle’ of the title, uncle to the narrator whom he has been abusing since she hit puberty. She has taken revenge on him but only after catching him in the act of raping yet another victim. Once again the sparseness of Woodrell’s prose shines through the darkness of the material: ‘He can’t talk since his head got hurt, which I did to him.’ The narrator knows she has Uncle at her mercy and her revenge is relentless: ‘You finally get an ogre under your thumb and you can’t hardly keep from torturing him some at first.’ Even a story as black as this is shot through with a grotesque humour. One day she dresses him in a frilly pink dress, does his hair in a bun, and uses ‘the whole bucket of Ma’s makeup on him’, before pushing him outside in his wheelchair for ‘every passing neighbor and stranger to see’. There is an inevitability to the ending. She catches him looking at her ‘and his eyes was wanting what babies don’t even know about’. She wheels him to a gap in the railings on the bridge over the river. She dabs his mouth one more time, tidying the drool before the final line: ‘My baby ain’t meant for this world.’

If the first story is dark, the second, ‘Uncle’, is darker still. The first sentence is short and, we soon learn, disarming in its apparent benevolence: ‘A cradle won’t hold my baby.’ The ‘baby’ in question is a two-hundred-pound serial sexual abuser and rapist of young girls and women – the ‘Uncle’ of the title, uncle to the narrator whom he has been abusing since she hit puberty. She has taken revenge on him but only after catching him in the act of raping yet another victim. Once again the sparseness of Woodrell’s prose shines through the darkness of the material: ‘He can’t talk since his head got hurt, which I did to him.’ The narrator knows she has Uncle at her mercy and her revenge is relentless: ‘You finally get an ogre under your thumb and you can’t hardly keep from torturing him some at first.’ Even a story as black as this is shot through with a grotesque humour. One day she dresses him in a frilly pink dress, does his hair in a bun, and uses ‘the whole bucket of Ma’s makeup on him’, before pushing him outside in his wheelchair for ‘every passing neighbor and stranger to see’. There is an inevitability to the ending. She catches him looking at her ‘and his eyes was wanting what babies don’t even know about’. She wheels him to a gap in the railings on the bridge over the river. She dabs his mouth one more time, tidying the drool before the final line: ‘My baby ain’t meant for this world.’

In a 2009 interview with Southeast Review, Woodrell is asked about his short fiction:

Actually, after this novel, I might do a whole book of those. Little six-to-eight page, gruesome, backwoods spins. Neo-folk, expressionist spins. A lot of fun to write. For twenty years I’ve never had time to write short fiction because of novel deadlines and the need to pay the bills. Nobody gets excited when you say, “Hey, I’m thinking about doing a collection of short stories!” But I’ve done a few in the past year, and I said, “Gosh, that’s fun, after novels.” It’s like, you meet somebody at dinner, you’re in love by midnight, you have breakfast together, then you say ‘so long’ forever. It lasts just that length of time. It’s perfect.

Whether you class Woodrell as a regionalist, a ruralist, or a writer of ‘country noir’ – a term he is credited with coining – his work since his opening Bayou Trilogy of crime novels, published from 1986-1992, has been exclusively set among the working class of the Ozarks. He himself recognises that this is not a great selling point. ‘Trust me, when I first started and Give Us A Kiss first came out, it was no big plus to have it set in the Ozarks,’ he said, in a 2011 interview with litreactor.com. With the success of Winter’s Bone, however – the paperback has sold in six figures, where none of his previous novels had sold above five thousand – and a growth in the publication of ruralist collections in the past ten years, it would appear that setting your stories in backwoods, dirt-poor areas is no longer a disadvantage.

His stories achieve the balance of local vernacular with a poetic authority that the Chicago Tribune once said ‘could be ancient carvings on a tree’. It’s an apt metaphor; nature and the natural world, its wildness, fill his stories from first to last. In ‘Twin Forks’, Morrow is down from Nebraska to buy a campsite:

…he liked everything about the place – the steep hillsides of forest stripped for winter, the dour gray rock bluffs crouched near the river, the lonesome mumble of the passing wind, and these untamed people who shot at things to so plainly announce their sorrow.

Woodrell says he always starts with character, and as well as the individual characters he draws, it’s the character of the native Ozark – ‘these untamed people’ – that peppers the stories: ‘A few of these customers lingered to chat, but most said all they had to say with a slow nod hello and a jerk of the chin on the way out.’ As well as this broad stroke to describe a community trait, he also paints precise individual descriptions that frequently stand out. In ‘Twin Forks’, one girl has ‘muddy hands and unbridled hair, and her face suggested she’d yet to be pleasantly surprised by life.’ In ‘Returning the River’, the father is ‘the joking drunk who was so bitter when sober’.

Keith Rawson in his interview with Woodrell for litreactor.com describes his style as ‘starkly poetic’, and Woodrell acknowledges ‘there are some readers and reviewers who’d prefer it not to be that way’. He reveals that he does write what he calls prose poetry, but rather than have the’m published as such in journals, he often ends up using them in his novels. It is certainly the case that his writing frequently has the brevity, economy and subtlety of poetry, with depths and intricacies that reward repeated reading. One can imagine some of his sentences being laid out as a poem and standing up to an analysis of poetic technique. Take this description of an old woman asleep in ‘Black Step’:

Her sleep is a busy place and she speaks mushed words into the sheets, her legs walk to yesterday and back across the mattress, her eyelids totter as the eyeballs rush about in darkness, wanting to see everything they’ve ever seen again.

One could highlight the assonance of ‘sleep … speaks … sheets’ or ‘back … mattress’; the rhythmic repetition of ‘her eyelids totter as the eyeballs rush’.

One could highlight the assonance of ‘sleep … speaks … sheets’ or ‘back … mattress’; the rhythmic repetition of ‘her eyelids totter as the eyeballs rush’.

As with many writers, Woodrell has his tropes, his returning themes and favoured lexicon. One such is ‘bone’. It is perhaps no coincidence that his most commercially successful novel includes the word in its title. But the word crops up with noticeable frequency in his work, and his stories are no exception. In ‘Florianne’, about a father who knows his daughter has been killed but has never found her body, the father sees guilt in everyone’s faces: ‘Should I grab on him now while he’s handy and beat on him till he tells me where I can rake her bones together?’ In ‘Returning the River’, ‘Harky is feeling redeemed in his bones, raised in his heart, a much better son now than he was before dawn.’ Bone in Woodrell’s writing is symbolic of something primal, offering a twisted, perverse sense of the prelapsarian. And in none of his stories are you ever very far from nature. It is, for Woodrell, the proper way of things: ‘lazy old time had slowly reclaimed the place for trees and weeds and possums.’ Nature is often taking its revenge on the indignities man has inflicted upon it. In ‘Uncle’, the narrator puts bird feed into a pan and positions Uncle under trees with the pan on his lap. And when nature isn’t taking its revenge on man, it’s man taking out his frustrations on nature: the departing campsite owner’s parting shot, in ‘Twin Forks’, is to fire farewell bullets at the trees.

Frequently, it’s the majesty, purity and resignation of nature that forms a counterbalancing backdrop to the depravity and violence of the characters’ lives. In ‘Woe To Live On’, a story about civil war bushwhackers on a murderous rampage, the creek is nonetheless ‘a comfort to tongues dried gamy and horses hard rode’. In the same story, a carver of driftwood admits ‘many times the river’s hand carved more truly, and I bring no improvement’. When Dalrymple in ‘Dream Spot’ can’t bring himself to tell Janet he loves her, he finds solace in his inability to express emotion in the ‘foggy hollows and damp dark bark, the vast forest of trees…’

In this short collection Woodrell shows damaged, inarticulate, impoverished characters in ancient characterful landscapes, living lives of brutality lit by beauty. He is a chronicler of a rural life that most people never see, a life hewn from the rocks and trees of the Ozarks, and occasionally washed clean by its rivers and creeks.