('Dramatic Manhattan' © Blixt, 2011)

*

AUTHOR PROFILE: SUE KAUFMAN

by DIANA CAMBRIDGE

*

WHO was Sue Kaufman, and how did the Greek myth of Icarus and his hopeless flight into oblivion shape her life… and death? And why do I think that, out of all the writers and all the suicides in the world, her work merits much, much more than the meagre consideration it’s been given?

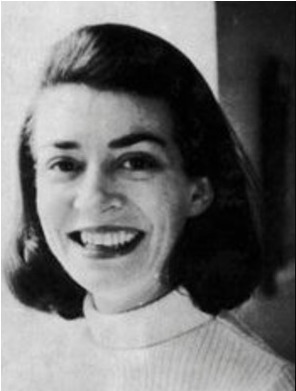

It’s forty years since she jumped from the balcony of the eighteenth–floor New York apartment in which she lived with her husband and son. When she died, she was fifty, and had written five novels – one of which, Diary of a Mad Housewife, was made into a film – and a collection of fifteen short stories, The Master and Other Stories.

While she was still at Vassar – where she majored in English and minored in art history and criticism – her first short story was bought for publication. It was one of the books of stories that formed her senior thesis. After graduating, she worked for Mademoiselle magazine for two years, as assistant to the fiction editor, before leaving to marry and write.

Let’s start with the Icarus complex – as defined by Henry Murray, a director of the Harvard Psychological Clinic and founder of the Boston Psychoanalytic Society. He coined the term to describe a particular type of over-ambitious character, as noted on mental health blog MyTwistedWonderland:

The concept of the Icarus complex […] is that when the gap between the idealized goal and reality is great, there is a greater chance that the endeavour will end in failure […] The complex associated with Icarus conveys the joy in flight, the pendulous emotional polarities, mania exhibited by flying too high, whereby he got burned – followed closely by his inevitable emotional crash that followed his flight of mania into depression – drowning in the sea of depression.

A meticulous observer of the Manhattan middle-class into which she was born, Kaufman depicted characters with delicate strokes of a barbed pen. Her themes – neurosis, depression, therapy, tranquillisers, the stress of city life, the domestic drudgeries of marriage, the social comedies of the Manhattan bourgeoisie, the ever-widening gap between the life she had and the one she’d expected – never made dreary reading. Her voice was rarely other than ironic and literary, blackly comic. But it was always, too, the voice of a woman who, having in childhood been given the promise of a life as a Jewish Princess, is in an interminable struggle with the slings and arrows of aching disappointment.

A meticulous observer of the Manhattan middle-class into which she was born, Kaufman depicted characters with delicate strokes of a barbed pen. Her themes – neurosis, depression, therapy, tranquillisers, the stress of city life, the domestic drudgeries of marriage, the social comedies of the Manhattan bourgeoisie, the ever-widening gap between the life she had and the one she’d expected – never made dreary reading. Her voice was rarely other than ironic and literary, blackly comic. But it was always, too, the voice of a woman who, having in childhood been given the promise of a life as a Jewish Princess, is in an interminable struggle with the slings and arrows of aching disappointment.

We see it – or at least I read it – most clearly in her short story ‘Icarus’, in which she records, in a third-person narrative, the day a mother gives birth. The birth, Kaufman writes, is ‘a burst of glory’, but not for long: ‘What – oh what – what had happened to the burst of glory with which the day began?’ the mother asks herself a few hours later, weeping. For some reason Pieter Breugel’s Fall of Icarus, a painting she loved, comes into her mind. This motif – the falling body, the dazzle of glory followed by the plunge into oblivion – haunts every one of Kaufman’s stories, and every novel. As does her shame about her emotions: in ‘Icarus’, the mother answers the phone to a friend, who is immediately concerned.

“Are you crying? You are! What’s wrong?”

Ashamed and distressed (was she sick in some way?) she mumbled that she did not know, then unexpectedly giggled and added, “Just a little postpartum depression, I guess.”

She can’t sleep just after giving birth:

[She] laughingly washed down the sleeping pill with champagne. Alcohol and Seconal – an overpowering combination, one would think, yet obviously not powerful enough for the terrible state of her nerves. She decided against ringing for another pill – ashamed, she didn’t want the nurses to know, and instead lit a cigarette. When she snapped on the gooseneck lamp, the room that sprang out of the shadow looked like a stateroom for some improbably luxurious voyage: flowers everywhere, a jungle of bottles on the bureau […] a teetering pile of gift boxes trailing ribbons to the floor.

Her husband, arriving hours later (though he was shown the baby, held up through a window, in dim light, just after he was born), drops a chaste kiss on her forehead, and asks for advice on how he’s “supposed to be – what are you supposed to do or say?” The unknown, smiling faces who attended the birth make the mother uneasy. “Who were all these people?” she questions – four decades before mothers in labour had, as of right, family or friends with them as they gave birth.

Her conclusion in ‘Icarus’ is that, after a long journey, she’s arrived at a point where she knows what her two most important things in life are: ‘One’s work and the people one loves’. But this, in itself, is ambiguous. The story’s final sentence – ‘Then she closed her eyes and dropped off at once into her first night of liable maternal sleep’ – hints at the difficulties to come… resentful children, chores, domestic timetables, no time for her own work, albeit in the cushioned ambience of wealthy Manhattan in which she was a privileged, yet nervous, inhabitant.

The major theme in Kaufman’s work is marriage, or at least the dream of marriage, as we still see it in the Anglo-American world – despite the massive growth of the divorce industry. Why does something that starts in a blaze of happiness scale down to grocery lists, bickering, and a feeling of being trapped? It’s not the people, but the institution, Kaufman challenges subtly.

Her apartment was high-end, she had a maid, her son was intelligent and well-behaved, and her husband was an eminent and devoted – but workaholic – doctor, who found the best therapists and paid any bill to help his wife through her depressions. Yet still, she wrote in her novel Falling Bodies, the poet Sacheverell Sitwell’s ‘early morning of the senses, with a cold and energetic freshness, clear and brilliant light’ was terminally submerged in the repetition of marriage.

In maintaining the trappings of the comfortable, married life – in keeping the nuclear family show on the road – there were relentless, unavoidable chore lists for Kaufman, who owned up to being the planet’s most clueless housekeeper.

Kaufman was a vulnerable romantic who needed admiration, literary recognition, sex, and security. These conflicts emerge in her stories. Every now and then, wrote Anne Tyler in a New York Times book review, her work gives us a sense of layers unexposed, mysteries unsolved that we ourselves (we imagine) might solve if we consider them long enough on our own, if we concentrate hard, if we think deeply enough. That’s what comes through in ‘Icarus’.

Kaufman was a vulnerable romantic who needed admiration, literary recognition, sex, and security. These conflicts emerge in her stories. Every now and then, wrote Anne Tyler in a New York Times book review, her work gives us a sense of layers unexposed, mysteries unsolved that we ourselves (we imagine) might solve if we consider them long enough on our own, if we concentrate hard, if we think deeply enough. That’s what comes through in ‘Icarus’.

Her best-known work was Diary of a Mad Housewife, published in 1967 and made into a movie by Universal Studios in 1970 with Carrie Snodgrass in the title role. It was not a blockbusting success. Kaufman was asked in 1978, a year before her suicide, if she was allowed to give the screenplay the once-over before it was made. “No, alas,” she answered, adding:

“I feel the character of Jonathan, the husband, was made into too much of a caricature – and I felt they did not do enough with the setting, the madness of New York, an important part of the book.”

Her other novels, including Falling Bodies, in 1974, received less acclaim from the critics, although English critics seemed to warm to her words a little more than in the US: ‘Sue Kaufman writes with an exact and chilling humour that is often very funny if you don’t mind wincing while you laugh’, reported the London Daily Telegraph.

Inexplicably, though, Kaufman still takes only a walk-on part in the chronicle of English-language fiction. She’s remembered in the annual Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction – $5,000 awarded by the American Academy of Arts and Letters for the best published first novel or collection of short stories – but none of her novels or stories are in print today. Equally inexplicably, very little of substance is known about her short life. Kaufman was born in Long Island, New York. She received her degree from Vassar College in 1947. In 1953 she married a doctor, Jeremiah Abraham Barondess, with whom she had a son. No papers or interviews have been offered by her family. This is dignity: a stark contrast to the Facebook sentimentality of today, when clichés are churned out to meet every tragic situation. She gets a passing reference in Sex and Shopping: The Confessions of a Nice Jewish Girl, the autobiography of her close friend Judith Krantz. Krantz notes that Kaufman endured a long struggle with depression, and believed that she was scheduled to be re-admitted to a psychiatric hospital the day after her suicide. Krantz quotes from a letter she received from Kaufman:

The sad thing is that the Women’s Liberation Movement has created a backlash of sorts – and the subject of the unhappy middle-class wife is almost taboo…

Kaufman herself railed against being classed as a Women’s Lib writer: what she wrote about, she said, was the ‘madness’ of city life and its effect on people, on marriage.

In my view, Sue Kaufman is the paramount observer of the divided self – this comes over in ‘Icarus’ in a perfection of close detail: a constant inspection of the mysteries and ambiguities of the mind, the possible pain of reality, the waves of happiness and optimism, sometimes followed by bleakness. Her short stories lay bare the way many women feel and think – she opened the door to the reality of marriage in a way no other writer has. But it’s the simple things – the perfect management of words, the flawless dialogue, the grace, humility and humour of her short stories – that deserve to be properly honoured now. Her work is not just fiction, but also social history; a window into the middle-class 1960s. ‘Icarus’ could almost be a documentary of giving birth at that time. Kaufman’s body of work is absolutely ripe, today as never before, for reprint, for fresh observation, for discussion. Her life is over, and the way she lived has changed, but have we, as people, moved on?

~

Diana Cambridge is a journalist and author of three how-to books, two on writing. She’s a Society of Authors prize-winner and her short stories have been accepted by Burdall’s Yard Theatre, Bath. She was Writer In Residence to Sherborne Literary Festival for three years until 2015 – and was also a presenter with Glastonbury Radio for three years. She is “agony aunt” for Writing magazine. Currently she runs workshops in creative and non-fiction writing. Diana lives in Bath, UK.

Diana Cambridge is a journalist and author of three how-to books, two on writing. She’s a Society of Authors prize-winner and her short stories have been accepted by Burdall’s Yard Theatre, Bath. She was Writer In Residence to Sherborne Literary Festival for three years until 2015 – and was also a presenter with Glastonbury Radio for three years. She is “agony aunt” for Writing magazine. Currently she runs workshops in creative and non-fiction writing. Diana lives in Bath, UK.