photo by Ignacio Labella

by Shawna Vesco

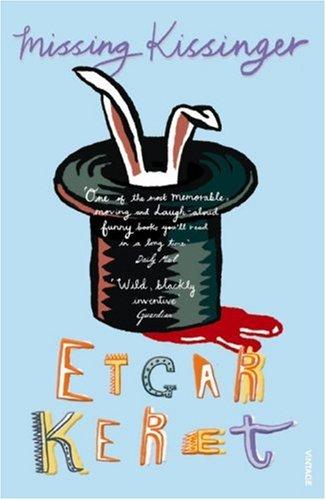

Etgar Keret, dubbed “Israel’s most radical and extraordinary writer” by The Observer, first went into publication in 1992 with Pipelines, a collection of short stories. This collection was largely ignored, but in 1994 (with the publication of his second book, Missing Kissinger), came more prominence on the literary and cultural circuits in Israel. Tel Aviv’s newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth named this second work one of the 50 most important works in the Hebrew language. In 1999 Keret’s work became accessible to English-speaking audiences for the first time through Jetlag, a compilation of five stories that had been adapted into graphic novellas. Keret’s next series of publications included Kneller’s Happy Campers (1998), The Bus Driver Who Wanted to Be God & Other Stories (2004), The Nimrod Flipout (2006) and Pizzeria Kamikaze (2006). Since 1992, Keret’s work has been translated into 31 different languages across 35 countries.

Keret’s influence is not exclusive to Israel’s literary landscape. In 2007 he directed the film Jellyfish, which was based on a story written by his wife, Shira. This film went on to win the Cannes Film Festival’s Camera d’Or Award, as well as the Best Director Award of the French Artists and Writers’ Guild. In the United States, Keret’s work is often featured on NPR’s radio programme This American Life. In 2011, Polish architect Jakub Szczesny built the famous ‘House of Keret’ in Warsaw. This house, measuring 120 centimeters at its widest point and 71 centimeters at its slimmest, is the thinnest house in the world. Like Keret’s writings, it is slender but dazzling in its simplicity. Furthermore, Tikkun Magazine explains that “Keret writes barbed sketches for Israeli television, pieces that have led to his being denounced in the Knesset as an anti-Semite”.

Keret’s influence is not exclusive to Israel’s literary landscape. In 2007 he directed the film Jellyfish, which was based on a story written by his wife, Shira. This film went on to win the Cannes Film Festival’s Camera d’Or Award, as well as the Best Director Award of the French Artists and Writers’ Guild. In the United States, Keret’s work is often featured on NPR’s radio programme This American Life. In 2011, Polish architect Jakub Szczesny built the famous ‘House of Keret’ in Warsaw. This house, measuring 120 centimeters at its widest point and 71 centimeters at its slimmest, is the thinnest house in the world. Like Keret’s writings, it is slender but dazzling in its simplicity. Furthermore, Tikkun Magazine explains that “Keret writes barbed sketches for Israeli television, pieces that have led to his being denounced in the Knesset as an anti-Semite”.

A second-generation Holocaust survivor who, in 1967, was born under the gaze of the Six-Day War, Keret writes to fulfill the historical, political and cultural exigencies placed upon him at his birth. As his literary horizon, Keret has a Kafkaesque absurdism that borders on grotesque and is steeped in irony. For work that is attuned to the political and cultural climates of Israel, this fierce pessimism is met as often with abhorrence as it is with acclaim. His short, pithy, and seemingly irreverent stories are often denigrated by an older generation, which includes Israeli intellectuals like A.B. Yehoshua, who claim Keret’s writings lack political clout. Yet, others claim that Keret’s work often questions the very foundations of “the political” and what politics means in a modern Jewish, not just Israeli, context.

Every time you see German products, whether it’s a television set or anything else, you should always remember that underneath the fancy wrapping there are parts and tubes that they made out of the bones and skin and flesh of dead Jews… Mom didn’t have a clue. She had never been to Volhynia House. Nobody had ever explained it to her. For her, shoes were just shoes and Germany was Poland.

~ from ‘The Bus Driver Who Wanted To Be God’

In an interview, Keret explains that “The moment Israel was formed, people gave up their Jewishness for being Israeli.” He says, “The writers became national figures. They lost the self-criticism that you find in Isaac Bashevis Singer or Woody Allen. I’m a lot closer to Hasidic tales than Yehoshua is.” Keret locates his work within this tradition of Jewish intellectuals and artists who find political efficacy in subversive, humorous and often deeply tragic representations of life. Keret, whose work harnesses the power of the fragmentary, is in the truest sense of the word a ‘storyteller’. His characters and narratives participate in ‘slice of life’ perspectives, rather than the genre of the national epic that has so dominated the Israeli literary scene. For Keret, the function and purpose of the short story genre is to interrupt identities, subjectivities, and time. He admits that since Israel is a young country, “the Israeli identity is still in a stage in which it can find this fragmentation…difficult to handle”. There is no subject that is off-limits for Keret whose work traverses Zionism, the Holocaust, suicide and – perhaps even most grotesque – the everyday.

In an interview, Keret explains that “The moment Israel was formed, people gave up their Jewishness for being Israeli.” He says, “The writers became national figures. They lost the self-criticism that you find in Isaac Bashevis Singer or Woody Allen. I’m a lot closer to Hasidic tales than Yehoshua is.” Keret locates his work within this tradition of Jewish intellectuals and artists who find political efficacy in subversive, humorous and often deeply tragic representations of life. Keret, whose work harnesses the power of the fragmentary, is in the truest sense of the word a ‘storyteller’. His characters and narratives participate in ‘slice of life’ perspectives, rather than the genre of the national epic that has so dominated the Israeli literary scene. For Keret, the function and purpose of the short story genre is to interrupt identities, subjectivities, and time. He admits that since Israel is a young country, “the Israeli identity is still in a stage in which it can find this fragmentation…difficult to handle”. There is no subject that is off-limits for Keret whose work traverses Zionism, the Holocaust, suicide and – perhaps even most grotesque – the everyday.

According to Gur’s theory of boredom, everything that happens in the world today is because of boredom: love, war, inventions, fake fireplaces — ninety-five percent of all that is pure boredom.

~ from ‘The Nimrod Flipout’

While this ‘anything goes’ whimsy might turn off the older generation to his writings, it seduces the younger generation. With stories like ‘The Girl on the Fridge’ and ‘Shoes’ – that smack of rebellion and political incorrectness – it is no wonder that “his books are the most stolen volumes from Israeli bookstores, and he’s the most widely read writer in prisons” (Tikkun Magazine). Yet, by the very same stroke of genius, he is also integrated into the Israeli curriculum in many schools because of stories like ‘Sirens’, which deals with Remembrance Day and the burden of memory in modernity. This rather schizophrenic reception of his work is indeed its very force.