photo by Larissa O’Duffy

by C.D. Rose

As soon as you see a picture, you know he’ll be good.

His head looks like a sculpture, as spare and intense as a granite block, with a massive forehead, a nose like a weapon and unfathomable eyes. Even in the grainy black-and-white shot on the back of the books, the face is that of a man who would make you laugh even as he told you how he plotted to murder children. It is a face much like the stories he wrote.

He was born Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev, in St Petersburg in 1905. Around the time the city itself changed its name, so did Daniil. Not a man to be pinned down by one identity, he variously signed himself DanDan, Shardam, Khorms, Charms and Kharms-Shardam, but Kharms is the name that appears on the books that have come out, long after his death. No one knows quite why he settled on this name, but his love of Sherlock Holmes (the Russian pronunciation of ‘Holmes’ being similar to ‘Kharms’) is a clue, as is the word’s near-homophony with the English ‘charm,’ or ‘harm.’

He was born Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev, in St Petersburg in 1905. Around the time the city itself changed its name, so did Daniil. Not a man to be pinned down by one identity, he variously signed himself DanDan, Shardam, Khorms, Charms and Kharms-Shardam, but Kharms is the name that appears on the books that have come out, long after his death. No one knows quite why he settled on this name, but his love of Sherlock Holmes (the Russian pronunciation of ‘Holmes’ being similar to ‘Kharms’) is a clue, as is the word’s near-homophony with the English ‘charm,’ or ‘harm.’

Kharms is as Russian as you like, and a man of his era. In the early 1920s he cultivated a reputation for eccentric behaviour, parading up and down Nevsky Prospect wearing pyjamas or a velvet coat and smoking an outsize pipe. He knew the Dadaist zaum poets, but resisted joining any groups until he formed his own – the Oberiu collective, formed in 1928, and consisting solely of Kharms and his friend Alexander Vvedensky. While this group has earned a footnote in earnest discussions of futurism and formalism, the absurd and the surreal – and gave Kharms the chance to write that most thrilling of literary forms, the manifesto – the fact is that Oberiu actually stood for very little: while the name may have officially been an acronym for the ‘Union of Real Art,’ Kharms later claimed he had chosen it precisely because it meant nothing at all. Similarly, in his apartment, Kharms kept a contraption made of rusty springs, empty cigarette packets, a bicycle wheel and some jam jars – Kharms said it was ‘a machine’, and, when asked what kind, replied: ‘No kind. Just a machine.’ Both Oberiu and the obscure machine are typical Kharms manoeuvres: disingenuously offering, then withholding.

In Kharms’ world old ladies invite themselves into your flat to die, or develop a habit of falling out of windows, shattering into pieces as they hit the pavement. Pushkin is incapable of sitting on a chair, and eventually has his legs replaced with wheels. People drink kvass and vodka, and the acquisition of bread and cucumbers is of primary significance. There is violence, lots of it; punches, falls, broken noses, lopped off limbs. Men in black coats appear at the moment of erotic climax, people disappear without warning. Stories end abruptly, often with a slap in the face to the reader, or an assertion that the writer can’t be bothered anymore. ‘And that’s all,’ is a common ending, or sometimes ‘And that’s all there is to it,’ or ‘I would write more, but suddenly the ink pot has disappeared.’

His stories are grim jokes where every line is the punch line. Gogol starved to the bone, Dostoevsky rewritten by David Shrigley.

And though I use the word ‘stories’, it hardly seems to fit. Kharms called his pieces sluchai – a near-untranslatable word which could mean event, incident, opportunity, occasion, emergency, circumstance or chance – all words which might better describe the formal challenge of his work.

Kharms combined the folk story (‘There was once…’ is a common opening) with the nightmarish illogic of the surrealists, the subversive play of Dada and the fragmentary construction of west European modernists, or his native constructivists. Then he added hunger, cramped apartments, bad alcohol and random violence to make work that reeks of early Soviet Russia.

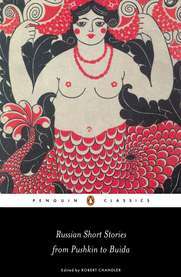

Not that these are museum pieces. In what we are often yawningly told is an age of brevity, Kharms gives us stories that could be sent by SMS, yet occupy a library. If you want the spare, lean, taut prose of the academy, there is none sparer, leaner and tauter than Kharms, who rarely spent more than a few dozen words on a story, and wasted none of them. The Old Woman, possibly his best story, is a veritable epic – Kharms’ War and Peace – extending to some twenty pages in the current Penguin Russian Short Stories. Yet there is nothing of the miniaturist in Kharms, he does not deal in flash fiction, he does not bother beautifully describing tiny epiphanies of everyday life.

Kharms plays games, but not our game. He doesn’t stick to the rules – telling a story and letting it develop in any of the possible ways we may expect. Sometimes it is hard to know what the rules of the game he is playing are – if, indeed, there are any at all – or if he is merely making them up or changing them at will as he goes on. The stories may stop at any moment (‘And that’s all’), leaving you breathless, frustrated and laughing at the same time. In these stories, Daniil charms, and Daniil harms.

Kharms plays games, but not our game. He doesn’t stick to the rules – telling a story and letting it develop in any of the possible ways we may expect. Sometimes it is hard to know what the rules of the game he is playing are – if, indeed, there are any at all – or if he is merely making them up or changing them at will as he goes on. The stories may stop at any moment (‘And that’s all’), leaving you breathless, frustrated and laughing at the same time. In these stories, Daniil charms, and Daniil harms.

You might, at this point, be thinking about the dread word whimsy – a pitfall for the small-scale fabulist – yet this is something Kharms avoids by miles. It’s not only the shocking, albeit cartoonish violence, nor those men in black coats who appear from time to time to make people disappear (giving us the uncomfortable shiver of a reminder that these stories were, after all, written under Stalin). Kharms avoids whimsy because his work, though funny in the blackest way, is so unremittingly grim. This is ‘Blue Notebook No. 10’:

There was once a red-haired man who had no eyes and no ears. Neither did he have any hair, so he was only theoretically red-haired.

He couldn’t speak, since he didn’t have a mouth. He didn’t have a nose either.

He didn’t even have any arms or legs. He had no stomach and he had no back and he had no spine and he had no innards whatsoever. He had nothing at all. We don’t even really know who we’re talking about.

In fact, we’d better not say any more about him.

And that’s it, as Kharms would say.

I know no story bleaker than this. It is a story which constantly refuses itself, minimal to the point of its own extinction. Antirational, nonlinear and illogical, his stories punch holes in the fabric of literature, they are tiny mysteries which refuse to tell their secret (that Holmes influence) and constantly deny exegesis. Beckett has something of Kharms – the slapstick violence, the mundane settings, the refusal – but Kharms is one of those rare writers whose work is so hermetically sealed it begets little else.

Reading this piece back, I see now how many negatives and ‘nots’ and don’ts’ there are in it. Kharms was a refusenik in every sense – half a century before the word was coined – refusing everything to find out what’s left, and discovering that there isn’t much, and laughing about it. These are stories (or events, chances, incidents) reduced to their nub, stories (emergencies, opportunities) which deal with the essential, being and non-being. And there is nothing more, or less, than that.

Eventually his writing and behaviour inevitably earned him the call in the middle of the night, the car outside, the men in black suits.

In prison, he claimed he didn’t suffer: “I was most happy when pen and paper were taken from me and I was forbidden from doing anything. I had no anxiety about doing nothing by my own fault, my conscience was clear.” And on his release he began to write darkly subversive stories for children, an activity which – other than write a manifesto – is the greatest thing a writer can do.

He spent most of the 1930s keeping his head down, filling notebooks, diaries and his desk drawer with ever smaller pieces, having ever less to do with other writers and the outside world, but somebody was reading, or watching.

The second time, there was no phone call. Just a knock on the door in the middle of the night and the big black car outside, waiting. He pretended to be mad to avoid the horror of the Gulag, and instead died of starvation in a mental institution in Leningrad. It was 1941 and the Nazis had come and laid siege to the city. Under such circumstances no one thought to feed the mad, apart from his wife, who arrived at the hospital with a food package only to be told her husband had died three days earlier.

The second time, there was no phone call. Just a knock on the door in the middle of the night and the big black car outside, waiting. He pretended to be mad to avoid the horror of the Gulag, and instead died of starvation in a mental institution in Leningrad. It was 1941 and the Nazis had come and laid siege to the city. Under such circumstances no one thought to feed the mad, apart from his wife, who arrived at the hospital with a food package only to be told her husband had died three days earlier.

And that was it. Like one of his own stories, Kharms had got smaller and smaller until he had almost, but not quite, disappeared.

Unlike his near-contemporary Bulgakov whose reputation has done nothing but grow, Kharms continues to fade in and out of view, and mostly out of it. On a recent trip to Russia I scoured bookshops and market stalls for his works, but found nothing, and on enquiring was met with nothing more than a shrug.

Having lived on little more than pickles, black bread, cheap vodka and his wits through one of the most brutal periods of the brutal twentieth century, and made great art nonetheless, Kharms was a man whose own life might be its own greatest story, but not one, you suspect, he would have wanted to tell.

Fascinating article CD. Do you find it surprising that the Russians aren’t celebrating the work of Kharms?