photo © William Creswell, 2010

by Rosemary Gemmell

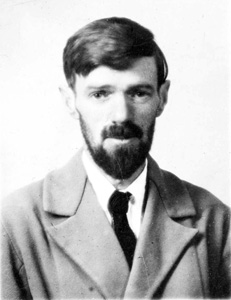

David Herbert Lawrence was born into a Victorian working class mining family in 1885, in Nottinghamshire, England. Like some of his fictional characters, Lawrence escaped from such humble beginnings by training as a teacher. His literary career began with writing poetry and stories, before his first novel, The White Peacock, was published in 1911. He continued to write until his death at the age of forty-four, in 1930.

Lawrence was a complex writer. Although famous for his novels, such as Sons and Lovers and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence also wrote and published essays, letters and poems. He was a prolific writer of short stories too, many of which convey similar themes to his novels – exploring relationships between men and women and the unique bond between mother and son. Most of the short stories first appeared in magazines before being published in collections, yet they have been largely overshadowed by his novels.

The Everyman publication of his Collected Stories, edited by Stephen Gill, contains fourteen of Lawrence’s stories, spanning the early part of the twentieth century. The first story in the collection, ‘The White Stocking’, was written in 1907, but was substantially reworked between 1913 and 1914. This short story runs the whole gamut of love, secrets, jealousy, violence and open-ended reconciliation between the main couple, Elsie and Ted Whiston. It opens when they are two years into their passionate and seemingly happy marriage, but the illusion is soon destroyed when a package arrives for Elsie on Valentine’s Day.

The Everyman publication of his Collected Stories, edited by Stephen Gill, contains fourteen of Lawrence’s stories, spanning the early part of the twentieth century. The first story in the collection, ‘The White Stocking’, was written in 1907, but was substantially reworked between 1913 and 1914. This short story runs the whole gamut of love, secrets, jealousy, violence and open-ended reconciliation between the main couple, Elsie and Ted Whiston. It opens when they are two years into their passionate and seemingly happy marriage, but the illusion is soon destroyed when a package arrives for Elsie on Valentine’s Day.

Elsie’s former employer and admirer, Sam Adams, has sent her a gift wrapped in a white stocking that once belonged to her. Attending a dance before her wedding, Elsie had accidentally taken the white stocking in her pocket, instead of a handkerchief. Allowing Adams to keep it, she appealed to Whiston not to confront him. But now the stocking becomes the means by which Adams sends jewellery to Elsie and she wears the pearl earrings he sends, almost as a testament to her own attractiveness in the eyes of another man.

Elsie knows she is provoking her husband to the limit and is fearful of what she might unleash, but she seems unable to prevent herself from taunting him to the point of violence:

She was rousing all his uncontrollable anger. He sat glowering. Every one of her sentences stirred him up like a red-hot iron. Soon it would be too much. And she was afraid herself; but she was neither conquered nor convinced.

One of the pleasures in reading Lawrence comes from his portrayal of male-female relationships. His depictions of these relationships are as relevant to twenty-first century readers as they were in his rapidly changing world. His changing views on this subject is evident in his varied work, but one of the most striking elements of Lawrence’s stories is that he knew enough about women to write about their emerging modernity and sexuality. The time and circumstances in which an author lives must influence him and, writing in the early years of the twentieth century, Lawrence was in a unique place to explore the changing perception of women in society and in literature.

Opinion has been long divided on whether his writing contained a strain of misogyny and chauvinism. Feminist critics, such as Simone de Beauvoir, writing in the 1940s, maintained that Lawrence portrayed women as subservient to men, while Seventies feminist Kate Millet is scathing about his attitude to women in Sons and Lovers. But each reader can bring their own experiences and attitudes to a text, and the reading can be influenced by the period in which the text is studied. By the 1980s, feminist critics began to recognise the sensitive portrayal of women in much of his writing. D.H. Lawrence himself suggested that man and woman are ‘separate and distinct identities until eternity’.

As a female reader, I recognise the duality and power struggles in many of the relationships portrayed in his work. He was able to empathise with female sexuality, independence and the need for any type of relationship to be built on respect and equality. It is perhaps not surprising that Lawrence writes with such understanding of the female psyche, as the women in his own life – his genteel mother, his deep female friendship with Jessie Chambers, and his eventual wife, the German aristocrat Frieda – had an overwhelming influence on the sensitive young man. His tempestuous marriage and sexual relationship with independent Frieda in particular gave Lawrence much of his raw material for the depiction of monogamy and infidelity in marriage, as well as the politics of male-female relationships.

Although many critics regarded much of his work as autobiographical, shifts in literary theory began to allow a more rounded analysis of Lawrence’s writing. Studies from feminist, Marxist and psychoanalytical approaches led to wider interpretation of his fiction. Lawrence himself seems to have been a complex and contradictory character, which makes it even more challenging to determine his aims in writing fiction. In his Collected Stories, Gill quotes the writer’s advice: ‘Never trust the artist, trust the tale.’ On the other hand, the  critic F.R. Leavis, in his 1955 publication D.H Lawrence: Novelist, states that ‘it is impossible to study the work and art without forming a vivid sense of the man, and touching on the facts of his history’. When exploring Lawrence’s work, I think it is important to give consideration to both the texts themselves and the experiences that the author brings to the tales from his own life.

critic F.R. Leavis, in his 1955 publication D.H Lawrence: Novelist, states that ‘it is impossible to study the work and art without forming a vivid sense of the man, and touching on the facts of his history’. When exploring Lawrence’s work, I think it is important to give consideration to both the texts themselves and the experiences that the author brings to the tales from his own life.

Sons and Lovers is regarded as one of Lawrence’s most autobiographical novels. Similarly, ‘The Odour of Chrysanthemums’ deals with a wife’s growing contempt for her miner husband, a contempt which the aspirational Mrs Frieda Lawrence evidently displayed towards Lawrence’s own father. Written in 1909, before being revised prior to publication in 1914, the story is a bleak yet profound picture of marriage, told mostly from the wife’s point of view. The main character, Elizabeth Bates, is a miner’s wife waiting for her husband to come home from work, knowing that he usually stops at the pub, returning late, the worse for drink. Lawrence engages the reader’s sympathy with the wife as she feeds her children in growing anger:

It is a scandalous thing as a man can’t even come home to his dinner! If it’s crozzled up to a cinder I don’t see why I should care. Past his very door he goes to get to a public-house, and here I sit with his dinner waiting for him.

The chrysanthemums of the title signify various events in the couple’s life together, from the hopeful beginning of marriage and the children’s birth, to the ailing relationship and the first time the husband is brought home drunk. They also emphasise the difference between the beauty of the natural world and the dark industry around them that can crush a man just as easily as flowers. The story takes a different turn in the second part when Elizabeth’s husband, Walter, is brought home dead from the pits and she must confront the fact that, before his death, their marriage had become a sham and her expectations towards her husband were unreasonable:

Life with its smoky burning gone from him, had left him apart and utterly alien to her. And she knew what a stranger he was to her. In her womb was ice of fear, because of this separate stranger with whom she had been living with one flesh. Was this what it all meant – utter intact separateness, obscured by heat of living? In dread she turned her face away.

Another aspect of Lawrence’s writing is the sensitive and sensual descriptive power of the language in his short stories, poetry and novels. In ‘Daughters of the Vicar’, from The Prussian Officer, we meet two sisters, Mary and Louisa, with very different approaches to marriage. Mary sacrifices herself and her body to marriage with a domineering and an unattractive clergyman to escape a genteel poverty, reminding me of Charlotte in Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Louisa falls in love with a local collier, Alfred. Although her mother and father hardly approve of such a choice, the reader knows that Louisa at least will be happy, wherever she and her husband live.

There is a touching passage, in the early days of Louisa and Alred’s relationship, when Louisa offers to go down and wash the dirt from the man’s back, in place of his dying mother, and she suddenly recognises this dirt-stained, working man’s worth:

His skin was beautifully white and unblemished, of an opaque, solid whiteness. Gradually Louisa saw it: this also was what he was. It fascinated her. Her feeling of separateness passed away: she ceased to draw back from contact with him and his mother. There was this living centre. Her heart ran hot.

D.H. Lawrence might still divide opinion, but his ability to set a scene, convey deep emotions and show us characters at play, love and war, infuse his short stories with a quality that transcends the time in which they were written. His fiction confronts issues around gender roles (such as the advancement of females in education, the supposed emasculation of the male, and the place of marriage in modern life) that are still relevant today, giving readers the opportunity to confront their own experiences. For a writer who was regarded with censure and frequent distaste in his own lifetime, D.H. Lawrence has left a profound legacy of stories that explore what it means to be human, fragile, and capable of great love and deep cruelty, whether male or female. Both the author and his work are contradictory and complicated and it rests with the reader to interpret each story themselves, while enjoying Lawrence’s exploration of changing human relationships.