('Boogie Man Nebula' © Kees Scherer, 2016)

*

‘WHAT HELD THE FLESH TOGETHER?’

ABJECT ADAPTATION IN THE THING

by CHRIS MACHELL

*

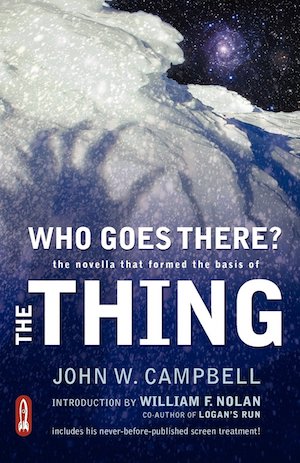

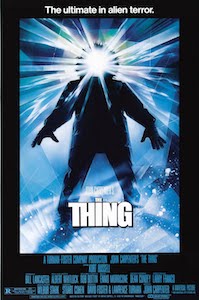

John W. Campbell’s 1938 short science-fiction story, ‘Who Goes There’, is one of the most influential works of its kind but is probably best known as the 1982 film, John Carpenter’s The Thing. Carpenter’s film is the second adaptation of Campbell’s story, the first being the 1951 The Thing From Another World. Both adaptations are excellent, but Carpenter’s film, in particular, is a masterclass in tension, paranoia and existential threat. The Thing was also remade in 2011, as a wretched pseudo-prequel notable only for its contempt for everything that made John Carpenter’s 1982 film such a triumph. More successful, however, was The Thing’s return to the literary form as Peter Watts’ short story adaptation, ‘The Things’, published in 2010. Here, the story is told from the alien’s perspective, depicting the extraterrestrial sympathetically as it tries to make sense of the strange world and beings around it.

~

Read Peter Watts’ short story

‘THE THINGS’

~

Although the various iterations of The Thing differ from each other, they all follow the same basic plot: scientists at a remote polar research station discover a crashed alien space craft with a lone, frozen occupant, apparently dead. The team bring the alien back to their station to study it, where it unexpectedly revives and kills them one by one. In all versions except The Thing From Another World, the alien is a shapeshifter, absorbing the bodies of the scientists to disguise itself as them, slowly spreading itself through the team. As one character succumbs after another, the survivors’ collective paranoia ramps up until no one can trust each other.

Although the various iterations of The Thing differ from each other, they all follow the same basic plot: scientists at a remote polar research station discover a crashed alien space craft with a lone, frozen occupant, apparently dead. The team bring the alien back to their station to study it, where it unexpectedly revives and kills them one by one. In all versions except The Thing From Another World, the alien is a shapeshifter, absorbing the bodies of the scientists to disguise itself as them, slowly spreading itself through the team. As one character succumbs after another, the survivors’ collective paranoia ramps up until no one can trust each other.

The Thing, in all its guises, is informed by a deep-seated anxiety around bodily transgression, being a manifestation of the fear that the body is not a fixed, distinct unit. The act of reproduction itself becomes abject, where bodies join together to transform and transgress liminal boundaries.

In the 1951 film, the action is relocated from Antarctica to the Arctic, and the alien no longer shape shifts. Although it is humanoid in appearance, the creature derives from plant life, picking off the characters to harvest their blood for food. It’s unclear why director Christian Nyby and producer Howard Hawks (rumoured to have been the film’s ghost director) deviate from Campbell’s original story, but the film retains both the paranoia of the novella while expanding on its latent crisis of masculinity.

Of the three major versions of the story, The Thing From Another World is the only one to feature a woman character, with Margaret Sheridan playing Nikki, a member of the team and very close friend to hero Captain Patrick Hendry (Kenneth Tobey). Their sexual tension is juxtaposed with the Thing’s asexual seed-pod reproduction, providing a counterpoint to the Carpenter and Campbell method of reproduction by assimilation. In addition, Dr. Carrington’s (Robert Cornthwaite) theory that the Thing’s intellectual and technological ‘development was not handicapped by emotional or sexual factors’ foreshadows the speech that Ash (Ian Holm) gives at the end of the 1979 film Alien:

You still don’t know what you’re dealing with, do you? The perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility […] I admire its purity. A survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.

The irony is that in Alien, the xenomorph that terrorises the crew is profoundly sexual. A cross-gendered manifestation of psychosexual anxiety, it is a biomechanical nightmare response to Nyby and Hawks’ asexual plant predator. Although not a direct adaptation of The Thing, the inspiration for Alien‘s claustrophobic isolation, its creature, and even its duplicitous science officer can be traced to The Thing in its 1938 and 1951 guises.

The irony is that in Alien, the xenomorph that terrorises the crew is profoundly sexual. A cross-gendered manifestation of psychosexual anxiety, it is a biomechanical nightmare response to Nyby and Hawks’ asexual plant predator. Although not a direct adaptation of The Thing, the inspiration for Alien‘s claustrophobic isolation, its creature, and even its duplicitous science officer can be traced to The Thing in its 1938 and 1951 guises.

Where the xenomorph attacks the crew by symbolically raping them, Campbell’s alien attacks its victims by destabilising their masculinity, transforming their solid bodies into shapeshifting jelly. Campbell describes the heroic McReady – without too much subtlety – as a monument to masculinity:

McReady was a figure of some forgotten myth, a looming bronze statue that held life […] the cold of the frozen continent leaked in, and gave meaning to the harshness of the man. And he was bronze – his great red-bronze beard, the heavy hair that matched it. The gnarled, corded hands gripping, relaxing, gripping and relaxing on the table planks were bronze. Even the deep-sunken eyes beneath heavy brows were bronzed.

In contrast, the Thing is formless and mutable, shifting from one shape to another according to need. As biologist Blair explains,

…every living thing is made up of jelly […] This thing was just a modification of that same world-wide plan of Nature; cells made up of protoplasm […] Only in this creature, the cell nuclei can control those cells at will.

The Thing’s cellular adaptability threatens the crew’s masculine autonomy not by devouring its victims, or even by using them as hosts for its spawn, as the xenomorph does in Alien, but by becoming them from the inside out. Assimilation is a well-worn trope of science fiction, from the pod people of Invasion of the Body Snatchers to the Borg of Star Trek: The Next Generation, but The Thing depicts a special kind of assimilation – the horror of bodily corruption and transgression.

Peter Watts’ short story inverts this sense of abjection by retelling Carpenter’s film from the perspective of the shapeshifting creature. As an entity for whom individuality itself is alien, it is shocked that the men, describing them as ‘offshoots’, attack it when it offers ‘communion’ by assimilating them. To the Thing, it is the compartmentalisation of individuality that is abject. As the Thing’s cells gradually take control of the host bodies, it searches in vain for the ‘soul’ controlling the machine, interpreting the brain as a cancerous growth:

I wore these skins as I’ve worn countless others, took the controls and left the assimilation of individual cells to follow at its own pace […] But I could only wear the body. I could find no memories to absorb, no experiences, no comprehension […] I threaded further into limbs and viscera with each passing moment, alert for signs of the original owner.

Instead, it finds entities utterly unlike anything it has previously encountered, fixed into one shape, singular and alone. To the thing, each individual human is wretchedly adrift in an abyss of immutable solitude, with ‘no plasticity, no way to adapt; every structure is frozen in place’. Watts characterises Campbell’s hyper masculinity of bronze and steel as a segregating prison that reduces the communicative potential of ‘communion’ to the crude ‘grunts and tokens’ of verbal language. To the creature, human intellect is no more than a Chinese room processing meaningless gestures and symbols.

Instead, it finds entities utterly unlike anything it has previously encountered, fixed into one shape, singular and alone. To the thing, each individual human is wretchedly adrift in an abyss of immutable solitude, with ‘no plasticity, no way to adapt; every structure is frozen in place’. Watts characterises Campbell’s hyper masculinity of bronze and steel as a segregating prison that reduces the communicative potential of ‘communion’ to the crude ‘grunts and tokens’ of verbal language. To the creature, human intellect is no more than a Chinese room processing meaningless gestures and symbols.

Watts’ Thing sees itself as a cosmic consciousness spreading knowledge and wisdom throughout the universe, expanding its sentient dominion through bodily assimilation. It is not the B-Movie monster of Nyby and Hawks’ film, nor is it the malevolent predator of Carpenter and Campbell’s iterations. Instead, it is, variously:

…an explorer, an ambassador, a missionary. I spread across the cosmos, met countless worlds, took communion: the fit reshaped the unfit and the whole universe bootstrapped upwards in joyful, infinitesimal increments. I was a soldier, at war with entropy itself. I was the very hand by which Creation perfects itself.

As an assimilator of countless worlds, saving them from their own forsaken solitude, ‘reshaping the unfit’, taking ‘communion’, the Thing is a religious fundamentalist. When the Thing confronts humans whose consciousness is spread not throughout our bodies but confined to the overgrown, segregated ‘thinking cancer’ in our skulls, it is nothing short of an existential crisis for the alien. In a distorted echo of the gospel song ‘Amazing Grace’, the creature resolves to save humanity from itself, realising that ‘I was so blind, so quick to blame. But the violence I’ve suffered at the hands of these things reflects no great evil … How could I leave them like this?’

As the Thing learns the crew’s language, its understanding is set in an increasingly human framework. When penultimate survivor Childs is assimilated, his dying conscious says to the alien, “you motherfucker. You soul-stealing, shit-eating rapist”. His fading utterance gives the alien a human context for assimilation, a loaded term for native speakers, but as alien to the creature as the concept of fixed bodies: sexuality is surely meaningless when individuality doesn’t exist. The Thing’s forced bodily communion is a symbolic sexual assault made literal by its horrifying final vow to ‘rape [humanity’s] salvation into them’.

Each version of The Thing builds upon the last, reshaping itself with each new adaptation. The masculine crisis of ‘Who Goes There’ is complicated by the sexual tension in The Thing From Another World, which is subsequently rendered into the body horror of Carpenter’s gruesome 1982 film. Watts then inverts the creature’s asesxuality with Childs’ parting words, giving the alien a perversely sexualised context in which to understand itself. Threading itself through film and literature as well as the bodies of its victims, The Thing renders culture itself as an abject body, absorbing, adapting and transforming.

~

Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner, and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue. He has a particular interest in genre and trash cinema. Chris has also written features for Little White Lies magazine and occasionally writes about video games. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack. Chris’ favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is Shenmue, a glorious exercise in hubris that hardly anyone played.

Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner, and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue. He has a particular interest in genre and trash cinema. Chris has also written features for Little White Lies magazine and occasionally writes about video games. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack. Chris’ favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is Shenmue, a glorious exercise in hubris that hardly anyone played.

One thought on “Abject Adaptation in The Thing”

Comments are closed.