photo by Skunkworks Photographic

by Morgan Omotoye

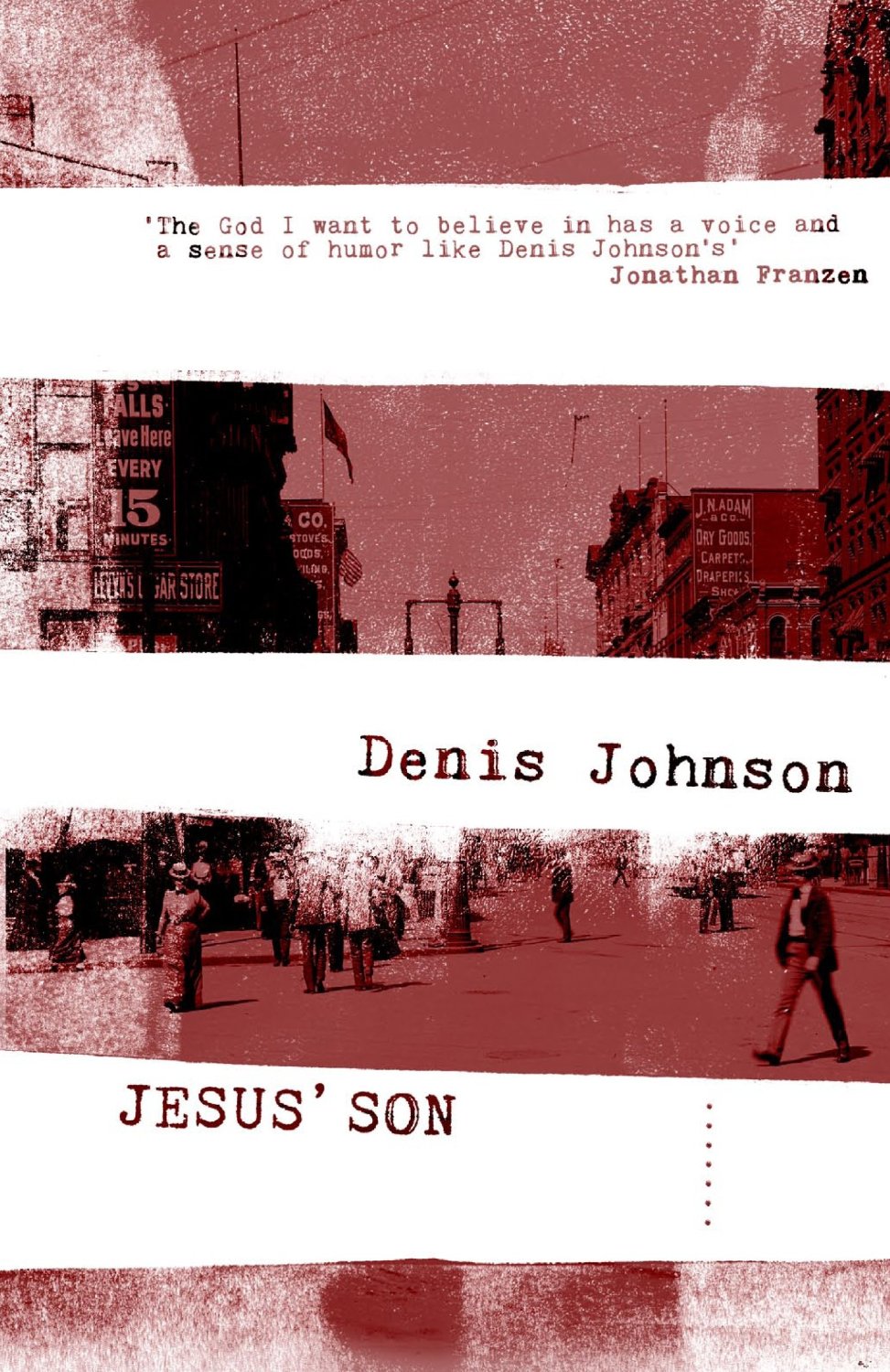

In Denis Johnson’s 1992 collection of interconnected short stories, Jesus’ Son, the main character is called Fuckhead. My favourite story in the collection is ‘Two Men’, in which our narrator is trying to return home from a dance at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Hall.

He has been at the dance with two friends he ‘hates’, maintaining that their friendship is a ‘false coalition’ based on ‘something erroneous, some basic misunderstanding that had yet come to light’. In fact, at the beginning of the story, he has forgotten his two friends are with him, such is his utter contempt for them. At the dance, Fuckhead kissed and put his hands down the pants of the ex-wife of an acquaintance, and he is now paranoid her new boyfriend, Caplan, ‘a mean, skinny intelligent man I happened to feel inferior to’, will hurt him.

I wondered, every second, if he would come back with some friends and make something painful and degrading happen. I was carrying a gun but it wasn’t as if I would actually have used it. It was so cheap, I was sure it would explode in my hands if I ever pulled the trigger.

As readers, we are invited to feel Fuckhead’s apprehension, to worry for him and, due to the narrative unfolding in the first person, Fuckhead’s subjectivity is ostensibly our own.

We learn Fuckhead and his two erstwhile companions will burgle a pharmacy and later abandon one of their number, leaving him bleeding at the back of a hospital. However, despite this knowledge, we still sympathise with Fuckhead because he believes he’s in danger; through Caplan’s character, Johnson has presented Fuckhead’s vulnerability.

Fuckhead and his friends leave the dance and head towards his car. It is here that they meet a stranger who guides the rest of the story forward. ‘My two friends and I went to get into my little green Volkswagen and we discovered [… a] man, sleeping deeply in the back seat.’ The three companions quickly discover this inebriated individual cannot hear or speak. He uses sign language to communicate. Fuckhead and his friends decide to be helpful and compassionate, offering the stranger a lift home. Their journey takes place along dark deserted streets in which ‘the buds were forcing themselves out of the tips of the branches and the seeds were moaning in the garden’. Not exactly Eden, but something paradisaical transmogrified, over-ripe and spilling with subterranean threat.

The stranger in the back seat of Fuckhead’s car is described in purely animal terms – ‘bulky as a ape’, ‘something of a hulk’, dangling ‘his hands as if he might suddenly go down and start walking on his knuckles’ – and he directs our companions to three different locations.

The stranger in the back seat of Fuckhead’s car is described in purely animal terms – ‘bulky as a ape’, ‘something of a hulk’, dangling ‘his hands as if he might suddenly go down and start walking on his knuckles’ – and he directs our companions to three different locations.

In the first house, a woman is glimpsed through an upper window: ‘All of her was invisible except the shadow of her hand on the curtain’s border.’ Fuckhead is so ‘flooded with yearning I thought it would drown me’, even as she declares, “If you don’t take him off our street I’m calling the police,” when she spots their bulky passenger.

At the second house no one is home and Fuckhead, peering through a window, notes, ‘I thought I could make out designs all over the floor like the chalk outlines of victims or markings for strange rituals’.

The third and final house is filled with ‘jocks’. Fuckhead and his friends feel like ‘stupid failures’ amongst ‘ghost-complected women’, and our main character is confronted with a woman who ‘hurt me. She looked so soft and perfect like a mannequin made of flesh, flesh all the way through’.

By this point, the stranger they’ve been trying to take home has ‘voiced plenty of desires but hadn’t said a single word. More and more he began to seem like somebody’s dog.’ This man has begun to grate on Fuckhead’s last nerve, so much so that Fuckhead and his companions try to ‘ditch him’ at the third house.

Part of what makes ‘Two Men’ so compelling is the heightened hallucinatory quality with which the story unfolds, powered by the effortless gadgetry of a nightmare. We as readers, like the stranger, are carried along, through a world in which ‘shacks with dim lights inside them sunk to the bottom of all this darkness’.

All the men in Fuckhead’s car are strangers in a fallen, sunken paradise, failing to communicate, to connect in any real way, unmoored by that ‘false coalition’. This is, perhaps, why all the women Fuckhead encounters fill him with romantic longing. They inhabit or speak of a world he cannot access, they touch and ignite something in him. They are otherworldly, invisible, ‘ghost-complected’ and ethereal, and in this way they are very unlike his wife, who ‘was different than she used to be’, presumably because they had ‘a six-month-old baby I was afraid of, a little son’. By abandoning familial responsibility, Fuckhead has found himself marooned, exiled, in a hard drinking masculine world of shifting loyalties and sudden violence. And through his subjective first person viewpoint, somewhat fatally, we sympathise and identify with him.

Eventually, our companions manage to rid themselves of their passenger in a comedic but violent way. The stranger, managing to grip on to the door, runs alongside the car until Fuckhead, driving faster, yanks the stranger into a STOP sign. Luckily for the stranger, the sign is rotten and breaks and he is unharmed, though he looks like ‘someone who was trying to fit his head back on his neck’.

From the story’s opening, there has always been violence lurking at the periphery, like the many tentacled horrors of a story by Lovecraft. Johnson presents us with foliage that is ‘moaning’. A gun is so cheap it is likely to explode when fired. We are forewarned that one of Fuckhead’s companions will be left bleeding at the back of a hospital. And Fuckhead is petrified Caplan will find him and shoot off his legs. Grim auguries all.

From the story’s opening, there has always been violence lurking at the periphery, like the many tentacled horrors of a story by Lovecraft. Johnson presents us with foliage that is ‘moaning’. A gun is so cheap it is likely to explode when fired. We are forewarned that one of Fuckhead’s companions will be left bleeding at the back of a hospital. And Fuckhead is petrified Caplan will find him and shoot off his legs. Grim auguries all.

At the story’s end, Fuckhead breaks into the home of a man who sold him bad drugs. It is an old slight, but energised by his fear of Caplan, frustrated by his stymied efforts to help the stranger, and perhaps angered by the fact that he has not been punished for his own misdeeds, Fuckhead decides to settle the score.

He discovers a woman at the house with two sleeping children. Unlike the previous women Fuckhead has encountered, she is not psychically remote – not looking down from a high window, or an almost ethereal being – she is right there in the room with him, afraid. This woman and her children have been abandoned by Fuckhead’s prey, just as Fuckhead has abandoned his own wife and child, which possibly adds fuel to Fuckhead’s distemper. But it’s the remoteness of the women in the rest of the story that really strikes me here – his distant wife, even the woman at the start of the story, who Fuckhead shared the closest physical intimacy with, abandoned him. So what will he do now that he is finally close to a woman?

The woman tearfully explains Fuckhead’s quarry is not home. She is so terrified, ‘her eyeballs were positively shaking in her head’. Fuckhead forces her to the floor. Places the gun against her head. He says, “I don’t care. You are going to be sorry.” And these are the final words of the story.

My copy of Jesus’ Son is a German imprint, and so for German readers there are footnotes, translating the more complicated words of each short story. There is, however, no aid for the reader on this ending.

‘Two Men’ is not resolved; the stranger does not get home, Caplan does not show up, the gun introduced at the start of the story does not go off. We don’t even meet the second man of the title. It’s not so much the slight frustration felt with the story’s lack of closure that matters, but the fact we, as readers, have been carried along, like in a nightmare to an awful, terrifying place and left alone there. Abandoned.

Years after I read ‘Two Men’ its ending continues to reverberate and I’d like to think the reason it does is that it challenges me to be a better human being. In his introduction to the magnificent collection of short stories Tenth of December, Joel Lovel writes of George Saunders’ fictions, ‘It makes you wiser, better, more disciplined in your openness to the experience of other people’. This certainly applies to Jesus’ Son. Make no mistake, Fuckhead is a nasty piece of work. Yet throughout ‘Two Men’ I sympathise with him. For me, the genius of the story lies here and it makes the ending even more powerful, as we, as readers, are ultimately left with the machinations of our own imaginations.