photo by Mike Gabelmann

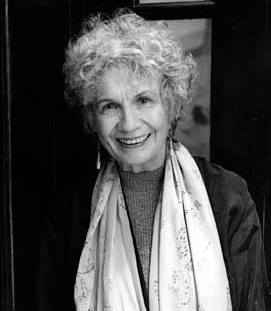

In her essay, shortlisted for the 2014 THRESHOLDS International Short Fiction Feature Writing Competition, Claire Thurlow profiles the life and writing of Alice Munro.

*

Comments from the judging panel:

‘A full and thoughtful overview of the Nobel Prize winning author and her work’; ‘clearly and carefully covers both Munro’s life and writing’.

*

by Claire Thurlow

Some critics claim that Canadian author Alice Munro is a miniaturist in the manner of Jane Austen, that she takes a small corner of the world and dissects its social mores with precision. For some, Munro’s focus on the minutiae of the everyday lives of ordinary people offers insufficient literary fireworks. Salman Rushdie, however, tweeted that Alice Munro is ‘a true master’ of the short story form, when she received the Nobel Prize for literature in 2013.

The Swedish Academy also lauded Alice Munro as a ‘master of the contemporary short story’ and as a ‘fantastic portrayer of human beings’. Compared to Chekhov for her flair with the genre, Munro reveals essential truths about ourselves in an unsentimental, yet deeply humane way. Having produced thirteen short story collections, Munro values her Nobel Prize as validation of the short story form; it isn’t ‘just something you played around with until you’d got a novel written’.

Born in rural Ontario in 1931, Munro returns repeatedly in her work to the landscape of her childhood, capturing the isolation of remote communities and the narrowness of small town life. Her childhood was difficult. Her father ran a struggling mink and fox farm, and with her mother suffering from Parkinson’s Disease, young Alice took over household chores and care of her younger siblings. Her upbringing was strict, in the Scottish Presbyterian tradition, centred on obligation and hard work. Yet, despite the hardships, reading was encouraged and Munro enjoyed making up stories on her long walk to school.

Marrying young, she moved to Vancouver and produced four daughters, one of whom died shortly after birth. The sadness that pervades much of her work may emanate from this painful memory. She began to write short stories while her babies napped, believing that writing a novel was unmanageable between housework and childcare. Yet even when her children were grown and she had more time to write, Munro saw no reason to abandon the short story form.

Her first collection, Dance of the Happy Shades, was published in 1968. The titular story centres on a children’s recital hosted by the elderly piano teacher Miss Marsalles. Munro pokes fun at the awkwardness of the invited mothers who struggle to find socially acceptable excuses for not attending this annual embarrassment. As a young mother in the suburbs of 1950s Vancouver, Munro would have heard all the excuses and been familiar with this sense of ‘doing the right thing’, and it plays a recurrent role in her writing. Her criticism may be sharply accurate, but it is not unkind. Munro’s personal experience, as well as that of her own unhappy mother, resonates in her perceptive portraits of vaguely discontented women.

Her first collection, Dance of the Happy Shades, was published in 1968. The titular story centres on a children’s recital hosted by the elderly piano teacher Miss Marsalles. Munro pokes fun at the awkwardness of the invited mothers who struggle to find socially acceptable excuses for not attending this annual embarrassment. As a young mother in the suburbs of 1950s Vancouver, Munro would have heard all the excuses and been familiar with this sense of ‘doing the right thing’, and it plays a recurrent role in her writing. Her criticism may be sharply accurate, but it is not unkind. Munro’s personal experience, as well as that of her own unhappy mother, resonates in her perceptive portraits of vaguely discontented women.

In ‘Dance of the Happy Shades’ we are presented with just these characters:

…women who have moved to the suburbs and are plagued sometimes by a feeling that they have fallen behind, that their instincts for doing the right thing have become confused.

They are aware of the gradual decline of Miss Marsalles into genteel poverty, yet they still feel duty-bound to accept the unwanted gifts and hospitality the old woman can ill afford to give. Munro gently mocks the superiority assumed by the young mothers over the ‘spinster’s sentimentality’ of Miss Marsalles, whose ‘idealistic view of children, her tender- or simple-mindedness in that regard, made her almost useless as a teacher’. Not a word is wasted in Munro’s austere, yet eloquent evocation of how this ‘ceremony’ must be endured with dignity.

Munro enjoys experimenting with the gothic. Miss Marsalles, who, year after year, wears the same archaic brocade gown and outmoded hairstyle, could be Miss Havisham’s kinder sister. The gothic atmosphere intensifies with the description of the fly-covered buffet that awaits the guests. While the food decays in the heat downstairs, Miss Marsalles’ ‘larger, grimmer’ sister is bedridden and dying upstairs. Like characters in a fairytale, the elderly sisters are grotesque, with ‘enormous noses’ and ‘long, gravel coloured’ faces; yet they are ‘sweet-tempered’ and ‘kindly’. In her description of them as naïve oddities, innocently happy in their own world, Munro foreshadows the arrival of the mentally disabled children who have also been invited to the party.

Munro has said that she admires writers of the American South, such as Eudora Welty and Carson McCullers. In ‘Dance of the Happy Shades’, she creates her own brand of sweltering discomfort and repressed emotions. The mothers become lethargic, assuming a dream-like state to disguise their irritation and boredom. Munro tells us with amusement of their ‘absurd nostalgia which would carry them through any lengthy family ritual’. They are roused from their polite torpor and transported into ‘some freakish inescapable dream’ with the arrival of the ‘little idiots’ from Greenhill School. The mothers are ‘repelled’; unsure whether it is appropriate to look at such children. But Munro does not flinch in looking at the children’s features in detail, giving us an unsentimental yet deeply touching picture of their ‘infantile openness and calm’.

When the last ‘special’ child sits down to play, Munro writes with black humour that ‘it cannot be said that anyone expected music’. But the girl unsettles the room with the simple, affecting joy of her performance.

The mothers sit, caught with a look of protest on their faces, a more profound anxiety than before, as if reminded of something they had forgotten they had forgotten.

Margaret Atwood once said that ‘Dance of the Happy Shades’ made her cry “because it was so good”. It is typical of Munro’s ability to recreate the mundanities of ordinary lives, but also to gently peel away the layers and reveal the raw emotions submerged beneath. There is great poignancy in her description of individuals who don’t fit in and obvious pleasure in her revelations of their small triumphs.

In 1972, Munro divorced her first husband and returned to her native Ontario, where she still lives today. From then on, she truly embraced her creativity, inspired by the landscape and small towns of her childhood. Munro argues that any human life can be  interesting if we only bother to look. With an archaeologist’s skill, she chips away at layers of human behaviour until she unearths the psychological conflicts that lie beneath. She is fascinated by time, and how its passage tints our memories of life, love and relationships.

interesting if we only bother to look. With an archaeologist’s skill, she chips away at layers of human behaviour until she unearths the psychological conflicts that lie beneath. She is fascinated by time, and how its passage tints our memories of life, love and relationships.

Julian Barnes states that Munro’s short stories ‘have the density and reach of other people’s novels’. Some of her stories are unusually long for the genre, for example, ‘Train’ from her 2012 collection, Dear Life. By taking twenty pages to unravel the unspoken sadness of her protagonist, Jackson, Munro allows herself the space to follow him forward through two decades of his life, circling back twenty-five years to finally disclose his secret.

Jackson is a young man returning home from war, who abruptly throws himself from a moving train and starts walking in the opposite direction. Munro shows us that Jackson is troubled, but does not tell us why. He talks of murdering a snake; his head is full of questions: ‘What are you doing here? Where are you going? A sense of being watched by things you didn’t know about.’ As he approaches Belle’s tumbledown farm, we are disturbed by his presence, and puzzled.

As years pass, Munro is cryptic about the nature of their relationship:

She was – he had found this out – sixteen years older than he was. To mention it, even as a joke, would spoil everything. She was a certain kind of woman, he a certain kind of man.

Seventeen years later, when Jackson takes Belle to Toronto for an operation, a nurse asks him to sign the paperwork. After some hesitation, he writes ‘friend’, but immediately abandons her in the hospital, fearful that he may be obliged to kiss Belle on the cheek.

As in many of Munro’s stories, the characters are more complex than they initially appear. Gradually, the layers are peeled away and we learn that Jackson’s inability to love and commit stems from the humiliation of childhood abuse. Munro has said that she likes to provide surprises, small intense shocks that might not work as effectively in a novel.

‘Train’ is one of the few stories where Munro chooses a male protagonist. Although not positioning herself as a feminist, she reasons that, as a woman, she is naturally interested in the details of women’s lives. In ‘To Reach Japan’, Munro gives a view of feminism through her narrator, Greta, a young mother and poet.

Feminism was not even a word people used … having any serious idea, let alone ambition, or maybe even reading a real book, could be seen as suspect.

Munro, when talking of her upbringing, has said that a woman ‘showing off’ or being too clever was frowned upon. As Greta says, ‘It was a woman’s shooting her mouth off that did it.’

In her 1971 collection, The Lives of Girls and Women, she links a series of short stories into a female bildungsroman. Her own uneasy relationship with her disabled mother provides material for ‘Friend of My Youth’, where painful events of the past are re-examined with the benefit of time. Yet the pain lies close to the surface, as seen in the bitterness of the narrator:

I felt a great fog of pieties and platitudes lurking, an incontestable crippled-mother power, which could capture and choke me. There would be no end to it. I had to keep myself sharp-tongued and cynical, arguing and deflating. Eventually I gave up even that recognition and opposed her in silence.

As shown in ‘Train’, Munro expertly analyses those sudden, irreparable choices in life that lead us away from our original track. The metaphor of train is repeated in ‘To Reach Japan’, where Greta’s sudden impetuous sexual liaison with another traveller leads to the disappearance of her young daughter. She is travelling to Toronto to house-sit for a friend and is due to return to the comfortable tedium of her marriage. Yet, another impulsive gesture – the sending of a letter to a man she barely knows – may take Greta away from the familiar tracks of her life.

As shown in ‘Train’, Munro expertly analyses those sudden, irreparable choices in life that lead us away from our original track. The metaphor of train is repeated in ‘To Reach Japan’, where Greta’s sudden impetuous sexual liaison with another traveller leads to the disappearance of her young daughter. She is travelling to Toronto to house-sit for a friend and is due to return to the comfortable tedium of her marriage. Yet, another impulsive gesture – the sending of a letter to a man she barely knows – may take Greta away from the familiar tracks of her life.

Munro’s interest in love and the often hidden intricacies of marriage recur in many of her stories. ‘Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage’, which was adapted as the 2006 film Away from Her, details the changing relationship between a man and his wife when she is suffering from Alzheimer’s. Such complications and cruelties of age and time are themes that Munro re-visits in stories such as ‘In Sight of the Lake’.

If Munro is a miniaturist, then she is an expert in the genre; the clarity of her prose is enhanced by the unique character of rural Ontario which she brings to her writing. In ‘Walker Brothers Cowboy’, she captures the humiliating poverty of the Depression era – Tuppertown in a ‘defeated jumble of sheds, the sidewalk gives up’ and even the weeds are ‘nameless, humble’. A young daughter accompanies her father, a struggling salesman – his wife calls him ‘a pedlar’ – on his rounds through a landscape that is ‘flat, scorched, empty’. The bleakness of land matches the harshness of life in these isolated communities. There is desperation in the line ‘Bush lots at the back of the farms, hold shade, black pine shade like pools nobody can ever get to’. Munro says that she wants her stories ‘to move people’, and it is hard not to be affected by her portrayal of this desolate landscape inhabited by characters stoically resigned to their fate.

Despite her admission that she still feels doubts that she can successfully translate an idea in her head to a story on the page, Alice Munro is surely one of the masters of the short story. Her ability to engage us in the emotional and moral dilemmas of ordinary people reveals not only essential truths about her characters, but also about ourselves.

One thought on “A True Master of the Form”

Comments are closed.