photo by Airwolfhound

by Jennie Ryan

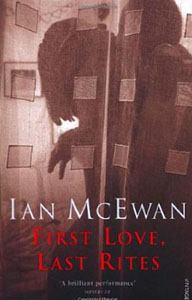

Now known more for his novels, Ian McEwan’s first published work was a collection of short stories, First Love, Last Rites, in 1975. This slim volume of eight stories foreshadowed many of the motifs that would populate his later works; the uncomfortable dichotomy of sexual awakening, incestuous lust, the claustrophobia and torment of obsessive love, and the ennui and despair experienced by those who have lost too many times.

I first read First Love, Last Rites when l was fifteen, only three years after its publication. I was testing the new waters of the tempting offerings sitting on the bookshelves of older friends. I immersed myself in an unfamiliar world, so stark, so bleakly sexual that l found it hard to navigate my way through on the first reading. The imagery of the stories brought to mind an environment crowded with the litter of innocence betrayed and perverted by desire and longing. Emotions and cravings that usually sit well below the surface are brought up for close and uncomfortable examination. I found I couldn’t look away. I still can’t, and l keep returning every few years for another view of McEwan’s cold take on troubled love.

In particular, I am often drawn back to the tale of an unnamed protagonist in ‘Butterflies’, in which McEwan powerfully evokes both the desolation of the urban landscape of London in the early 1970s and its equally emotionally desolate inhabitants.

The story tells of the narrator’s ultimately fatal encounter with his young neighbour, a little girl named Jane. Written in the first person, the story is recounted in a circular flashback, as the narrator is preparing himself for a meeting with the girl’s parents. It is revealed, quite early on, that he was the last person to see the girl alive. A slow unfolding of events draws the reader into the world of the narrator, an awkward, friendless social isolate whose role in the death of Jane is initially unclear.

McEwan writes his narration in short sharp sentences. This easily suggests the stunted, bleak emotional world of the narrator. The physical environment in McEwan’s story is also bleak; a grey, concrete sharp-edged world, devoid of life: ‘There are no parks in this part of London, only car parks’. The image of the canal sits heavily on the page and dominates the narrative, acting as an additional dark protagonist: ‘The brown canal which goes between factories and past a scrap heap, the canal little Jane drowned in.’ The canal is a place of empty broken factories, abandoned life and discarded humanity.

McEwan writes his narration in short sharp sentences. This easily suggests the stunted, bleak emotional world of the narrator. The physical environment in McEwan’s story is also bleak; a grey, concrete sharp-edged world, devoid of life: ‘There are no parks in this part of London, only car parks’. The image of the canal sits heavily on the page and dominates the narrative, acting as an additional dark protagonist: ‘The brown canal which goes between factories and past a scrap heap, the canal little Jane drowned in.’ The canal is a place of empty broken factories, abandoned life and discarded humanity.

When he is shown the corpse of the little girl who drowned in the canal, the narrator remains detached and uninvolved as he reflects on his past experiences with death. A dog’s death: ‘I saw the wheel go over its neck and its eyeballs burst. It meant nothing to me at the time.’ His mother’s death: ‘And when my mother died I stayed away, from indifference, mainly.’ He dispassionately describes the mundane surrounds of the mortuary, the finer details of the little girl on the table. He wants to touch her but feels the police sergeant and mortuary assistant are watching him, suspicious of him.

A meeting with the girl’s parents is suggested by the police sergeant who takes his statement: “You’re almost next door to them, aren’t you?” Although the narrator feels he is under suspicion, he looks forward to the meeting: ‘Still it was something, a meeting, an event to make sense of the day.’

Getting ready for the meeting the narrator’s memory is triggered by the smell of his bath soap. ‘I used the same soap on Thursday, and that was the first thing the little girl said to me, “You smell like flowers.”‘ The story then unravels to reveal his direct involvement with her death.

He first notices her as he walks past her garden. She follows him, asking him repeatedly where he is going. Initially annoyed, he finally looks at her closely, ‘She had a long delicate face and large mournful eyes. She was beautiful in a strange almost sinister way, like a girl in a Modigliani painting.’ He is happy to have someone to talk to, as the only other people he speaks to are Charlie, his neighbour, and Mr Watson who owns the local grocery shop. When she walks alongside him and hangs onto his arm his reaction is sharply visceral, ‘I felt a cold thrill in my stomach and l was unsteady on my legs’. His response alludes to the ultimately fatal connection he makes with her. He convinces her to walk to the canal with him.

She is hesitant, telling him she is not allowed near the canal. Her hesitation frustrates him so he tempts her with a promise of butterflies. Red and yellow butterflies he knows would never actually survive by the canal, because ‘the stench would dissolve them’. Their walk takes them over numerous bridges and through murky dank tunnels. While expressing her fear she stays with him and they travel further down beside the canal together. They move past the scrap yard and witness a group of young boys roasting a cat alive. With no real plan, he keeps moving her forward, keeping her close, fearful she will run home. At the entrance of another tunnel she finally says, “There aren’t any butterflies, are there?” Now he drags her into the tunnel, crying and screaming.

She is hesitant, telling him she is not allowed near the canal. Her hesitation frustrates him so he tempts her with a promise of butterflies. Red and yellow butterflies he knows would never actually survive by the canal, because ‘the stench would dissolve them’. Their walk takes them over numerous bridges and through murky dank tunnels. While expressing her fear she stays with him and they travel further down beside the canal together. They move past the scrap yard and witness a group of young boys roasting a cat alive. With no real plan, he keeps moving her forward, keeping her close, fearful she will run home. At the entrance of another tunnel she finally says, “There aren’t any butterflies, are there?” Now he drags her into the tunnel, crying and screaming.

The assault is brief. “Touch it, touch it”. He describes his solitary orgasm, ‘All the time I spent by myself came pumping out, all the hours walking alone and all the thoughts I had had, it all came out into my hand.’ In his relaxed aftermath, dealing with the cleaning of his hands in the canal, the little girl runs off. He chases after her, knowing the consequences for him should she tell of their carnal encounter. As they run she falls at the side of the canal and knocks herself out. His reaction is appropriately coarse: ‘I no longer wanted to touch her, that was all pumped out of me now, into the canal.’ He pushes her unconscious body into the canal, ‘”Silly girl,” I said, “no butterflies”‘. This is the last mention of the girl, who has become a used up, easily discarded agent for his pleasure, for his momentary release from a life of suffocating loneliness.

On his way to the meeting the narrator has a brief interaction with some boys playing soccer on the street. He ignores their ball, which has rolled near his feet. On walking away from them they throw a stone at him, which he traps neatly with his feet. The boys laugh and cheer him and momentarily he imagines going back and joining in their game. For him this was a rare opportunity to make a human connection. He describes himself as ‘elated’ at the thought of joining the group. He later sits on the library steps, waiting for his meeting and goes over this encounter, replaying an outcome where he does join the group: ‘I would be with them, one of them, in a team.’ He knows, however, that ‘opportunities are rare, like butterflies’. The narrator walks off to an unknown reception from the parents of Jane, no further thought of her, just regret for his own lost opportunities.

In ‘Butterflies’, the narrator’s extreme disengagement is a perfect example of someone experiencing, in one catastrophic event, both his first love and last rites. Many of the eight stories in the collection possess such misaligned, mostly young, protagonists. Generally damaged by abandonment, death, abuse these characters seek to gain love and affection in the most deviant and devastating ways. Some, for no known reason, are just unable (or unwilling) to follow their moral compass.

In ‘Homemade’, a young teenage narrator, urged on by his seemingly more experienced friend to have sex, violates his younger sister one night while his parents are out. Once the deed is done, he, like the narrator of ‘Butterflies’, treats his eleven-year-old unwitting ‘partner’ with disdain: ‘‘‘You’ve wet inside me” and she began to cry. Hardly noticing, I got up and started to get dressed.’ Again, echoing the dismal connection in ‘Butterflies’, the narrator here recognises that ‘this may have been one of the most desolate couplings known to copulating mankind, involving lies, deceit, humiliation, incest […] but I was pleased with it’.

The tale of another social and emotional outcast, ‘Conversation With a Cupboard Man’, is just that: the narrator, who lives in a cupboard, telling his life story to a social worker. His account reveals his mother’s obsessive love that infantilized him and kept him trapped in infancy until he was seventeen, when she met a man and abandoned him: ‘Overnight she just swapped obsessions and all the sex she’d missed out on caught up with her’. His life destroyed, he is then forced to ‘grow up’ and live in an adult world he is ill-equipped to function in. ‘How did I become an adult? I’ll tell you, I never did learn. I have to pretend.’ Adult life so confuses him that he constantly seeks ways to go back to the ‘safety’ of his early life. ‘I suppose I could have spent the whole of my life living my first two years over and over again and still not think I was unhappy.’ Time in jail and an experience being locked inside a heated oven evoke the feeling of safety he had when his mother was ‘trying to push me back up her womb…’ So he now lives in a cupboard: ‘I hate going outside. I prefer it in my cupboard. I don’t want to be free.’ He has found a way to remain the adult infant his mother loved but ultimately discarded.

In all of its short narratives, First Love, Last Rites throws a dark shadow across the society that shaped these emotionally barren individuals. And the reader is left to reflect on their own place in McEwan’s austere world.