('Lost' © ??1989, 2013)

A STORY YOU MUST READ AT LEAST TWICE: ‘FATHER, SON, HOLY RABBIT’

by KATHLEEN H. STORY

Stephen Graham Jones’ short story ‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit’ is a highly recommended read, and I will guarantee that you cannot read it just the once. By the end of the first reading you will ask yourself, Wait, did I get that right? and you will have to read it again. And if you are not yet a parent and later become one, you will want to read it at least a third time – although it might scare you to do so. By then you will realise how powerful your love is for your child, which will make you consider just how far you are willing to go to save its life.

Parents often say they would give their left arm or even their life to save their children. That they could kill anyone who tries to harm them. But would they really? This story will force you to question yourself.

The story will haunt you with vivid mental pictures, snow white and blood red in colour, and it will pull you in directions you won’t want to go. And if you have a weak stomach, it could well make you nauseous. For it involves eating a great deal of red raw meat – and vomiting it up again.

In the story, father and son are lost in the snowy woods without food. The father is anxious to find sustenance to keep the young boy alive when he resorts to feeding his son raw rabbit meat. Here, the boy wakes to see the bloody mess he has vomited on the ground:

[the boy] turned to his see if his father had seen what he’d done, how he’d betrayed him. His father was sleeping. The boy lay back down, forced the rabbit back into his mouth then angled his arm over his lips, so he wouldn’t lose his food again.

After several such feasts, the father needs two sticks to get around and has to sit with his legs out straight. You must read for yourself. I merely hint at the shocking ending.

Where should this story be placed on the short story menu: is it a moral lesson, a twist ending tale, a scary story, a cliffhanger, or fantasy? Nearly all stories encompass a problem and a solution of some kind. Twist endings seem most entertaining, with readers looking for clues to determine where the story is taking them. With this story, though, it will be startlingly impressive if you correctly envision the path it takes. At less than 2,600 words in length, your reading pace will quicken as you sprint through their ordeal to discover the characters’ fates.

The writer’s language is crisp and energy-filled, despite there being little dialogue between the two main characters and the descriptive action with a rabbit which the boy names Slaney. At times you will question what is factual and what is fanciful for a certain amount of delirium is expected in a story focusing on cold and half-starved humans. At one point the boy sleeping by his father wakes to voices he hears on a scratchy radio. He looks out and sees Slaney’s rabbit skin in the snow:

The boy crawled out to it, studied it, wasn’t sure how Slaney could be out there already, reforming, all its muscle growing back, and be here too. But maybe it only worked if you didn’t watch. The boy scooped snow onto the blood-matted coat, curled up by his father again.

The father carves his and his son’s initials into the tree harbouring them, followed by the boy’s mother’s name, and finally a picture of the rabbit, Slaney. It is an act whose twin messages seems portentous, a creation by a hopeless man who anticipates imminent death. He is acutely concerned for both his son’s state of mind and the effect of their disappearance on his wife. Firstly, the picture of Slaney is the father’s attempt to amuse, occupy, and encourage his son, drawing the boy’s attention away from his fears and reinforcing the conviction that the magical rabbit is aiding them. The boy, however, is left waiting by a tree while his father seeks food. One time, when his father doesn’t return ‘for nearly a day’, he climbs up into a tree, ‘then higher, as high as he could, until the wind could reach him’, and there he falls asleep. When his father finally returns, he ‘reached up with his stick, tapped him awake. Like a football in the crook of his arm was the rabbit. It was bloody and wonderful, already cut open.’

Secondly, the father carves and then repeatedly circles his wife’s name to reassure her that, if they do not survive, their last thoughts were of her. Her carved name also enshrouds father and son with their love for her during this life-and-death nightmare. The boy runs his fingertips over the carving and brings the taste to his mouth, gathering his mother to himself like a security blanket. With mother beside them, their family complete, everything will be okay.

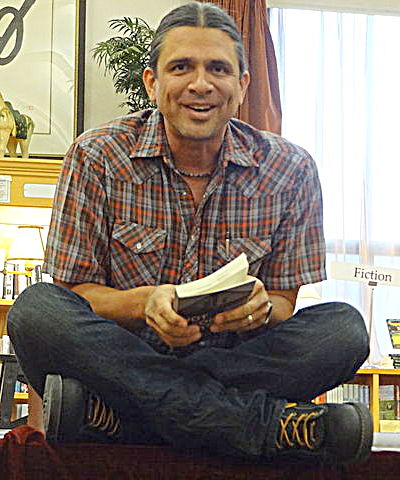

When asked what makes good writing Jones has said that a story comes alive when the reader identifies with a character who seems real and who acts as the reader’s ‘prose avatar’, encouraging him to ask What would I do? Jones also says that for him, writing fiction is like acting on a page instead of a stage: “It’s creating this made-up place and stepping into it, believing it, and that’s how the characters become real – they’re all you.”

So, did this story happen in Jones’ own life? ‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit’, he says, is the result of his reliance on a digital compass for which he hadn’t read the instructions. He and his Blackfoot father were hunting on an Indian reservation when they became separated and he got lost. He describes how he kept coming back to the same tree, surrounded by bear tracks, until night approached and he began getting very cold. Jones describes how a white rabbit ‘followed’ him until he shot it in the head and tied it to his belt. Now he’s walking around with a bloody rabbit and sees grizzly bear scat on the ground. When his walkie-talkie finally begins working, he is able to contact his dad who shoots his rifle to signal his location. Stephen hears the shots but within minutes he loses his radio. He ends up at a wolf’s den and it is a couple hours later when he lucks onto a logging road which takes him downhill to his father’s truck’s headlights. Though half-frozen, Jones not only survives but he retains his rabbit and the ingredients for ‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit’ which he wrote a couple months later.

So, did this story happen in Jones’ own life? ‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit’, he says, is the result of his reliance on a digital compass for which he hadn’t read the instructions. He and his Blackfoot father were hunting on an Indian reservation when they became separated and he got lost. He describes how he kept coming back to the same tree, surrounded by bear tracks, until night approached and he began getting very cold. Jones describes how a white rabbit ‘followed’ him until he shot it in the head and tied it to his belt. Now he’s walking around with a bloody rabbit and sees grizzly bear scat on the ground. When his walkie-talkie finally begins working, he is able to contact his dad who shoots his rifle to signal his location. Stephen hears the shots but within minutes he loses his radio. He ends up at a wolf’s den and it is a couple hours later when he lucks onto a logging road which takes him downhill to his father’s truck’s headlights. Though half-frozen, Jones not only survives but he retains his rabbit and the ingredients for ‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit’ which he wrote a couple months later.

Jones states that he writes stories that matter to him, and that he crafts them like art, going over them until they are cleaned and sculpted “toward a very specific purpose.” He aims, he says, for blind-leap endings, hoping there’s a ledge in the dark space. Just wait until you hit that ledge at the end of the dark space in ‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit.’

Although a relatively new writer, Jones has published hundreds of short stories and eleven novels. He has won many awards, and is an English professor on the MFA programme at the University of Colorado Boulder and UCR–Palm Desert, and lives in Boulder, Colorado with his wife, son, and daughter.

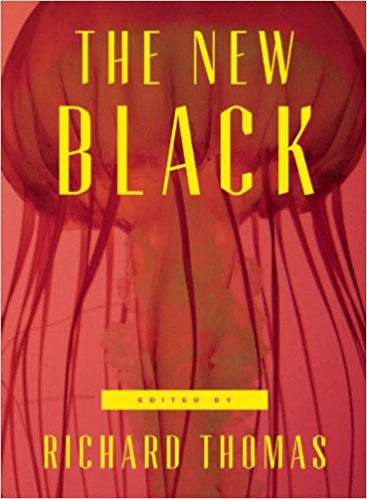

‘Father, Son, Holy Rabbit’ is included in the anthology The New Black, a collection of thirteen ‘neo-noir’ short stories, published by Dark House Press. Read more about this talented, prolific dark author on his website, http://www.demontheory.net/, on Twitter at https://twitter.com/SGJ72, and on Facebook at stephengrahamjones.

~

Kathleen Herrick Story won her first writing contest at age 14. Since then, she has written over a thousand non-fiction articles for the Internet Examiner. Her poems and shorts stories have also been published in places including 404Words and Poetry Nation. She is currently doing research on autism and is completing her first novel. She has degrees in education and computer science, but her lifelong passions have been language, books, and films, and storytelling of truth and fiction. Like one of her favorite writers, Stephen Graham Jones, much of her fictional writing is based on a multitude of life experiences.

Kathleen Herrick Story won her first writing contest at age 14. Since then, she has written over a thousand non-fiction articles for the Internet Examiner. Her poems and shorts stories have also been published in places including 404Words and Poetry Nation. She is currently doing research on autism and is completing her first novel. She has degrees in education and computer science, but her lifelong passions have been language, books, and films, and storytelling of truth and fiction. Like one of her favorite writers, Stephen Graham Jones, much of her fictional writing is based on a multitude of life experiences.

2 thoughts on “A Story You Must Read At Least Twice”

Comments are closed.