photo by Samantha Marx

by Kathryn Hall

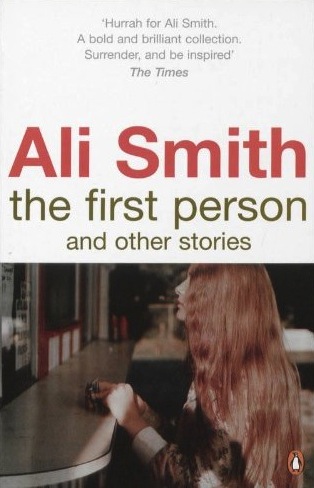

Unremarkable settings, familiar to contemporary, suburban British life, are synonymous with Ali Smith’s writing. The locations within her 2008 collection, The First Person and Other Stories, are entirely ordinary: a supermarket (Waitrose, to be precise), a café, the staircase of a family home. The focal points, too, are based in the minute and tedious miscellany of that life – the Yellow Pages, history homework, unwanted mail. Yet these things grow outwards, quite often fantastically, sweeping off at unexpected tangents.

It is the ideas of perspective that are the central point of departure in The First Person. Experimentation with perspective has proven fruitful ground for Ali Smith in her past work; in the novels Hotel World and The Accidental, respectively, tales of a young hotel worker’s untimely death, and of an unknown woman entering a family home and influencing the lives within, are woven together by accounts from and about a number of personalities, of a number of different ages and backgrounds. In this short story collection, though, experimentation with perspective really comes to the fore, as we can rightly infer from its title. In fact, the perspectives play as important a role as the narratives themselves, often becoming even more fundamental to our reading.

In ‘The History of History’, Smith plays with our expectations of language and the conventions that usually communicate certain types of people. Her teenage, first-person narrator – gender unspecified – has history homework to be getting on with, specifically ‘a newspaper report of the death of Mary Queen of Scots’. Aside from routine homework, this teen’s other main concern is what’s for tea. Homework and tea. Pretty much the extent of concern for any average teenager on returning home after a day’s schooling. On top of that, though, this teenager is dealing with the sense that their ‘mother’s gone mad’.

In ‘The History of History’, Smith plays with our expectations of language and the conventions that usually communicate certain types of people. Her teenage, first-person narrator – gender unspecified – has history homework to be getting on with, specifically ‘a newspaper report of the death of Mary Queen of Scots’. Aside from routine homework, this teen’s other main concern is what’s for tea. Homework and tea. Pretty much the extent of concern for any average teenager on returning home after a day’s schooling. On top of that, though, this teenager is dealing with the sense that their ‘mother’s gone mad’.

What are the signs of this maternal madness? Firstly, and perhaps most monumentally, mother has neglected to have tea on the table for her husband and daughter/son when they arrive home. Add to this the scene that greets the teen when arriving at the house. To begin, their mother is sitting on the stairs, with the dog, reading a Georgette Heyer book, only to then throw the book off in disdain and vow never again to read anything else so ‘full of shit’. And then, it’s the mother’s recourse to swearwords, her assertion of her identity as that of Margaret – not ‘mother’, nor ‘wife’ – and her decision to cut down the hedge at the bottom of the garden in order to ‘see so much further’. Here we have one unhinged mother. According to the narrator, at least.

What’s interesting here is that this could all be entirely unquestionable, ‘normal’ behaviour, if it weren’t that of a parent as perceived by their child. Tossing aside a dated and trite historical romance, reclaiming a sense of self and refusing to uphold a social convention, which puts women reluctantly in the kitchen in order to please their husbands and children, all seem reasonable to me. What’s more, most mouths have uttered the odd obscenity here and there. The image of a woman labelled ‘mad’ for her deviation from societal norms calls to mind the Victorian diagnosis of hysteria – placed on a woman who deviated from domesticity. Here, it brings the teenager’s perception of madness to the foreground, prioritising it over the true psychological state of the mother

As well as chiding their mother and reporting passive-aggressively on her behaviour over the phone to their father, ‘loud enough for her to hear’, the narrator passes comments of superior scorn in a language unlike that which we’d expect to hear from a modern teenager. ‘I very much disapproved’, they think, in relation to the swearing. There’s an amusing reversal of conventional roles at play here: the teenager playing the responsible grown-up at a loss, attending to the priorities (homework and tea), whilst the adult answers back and voices their angst. Even the manner in which the narrator talks about their mother to their best friend, Sandra, has the sense of more mature conversation; both stake their claim to being lumbered with the maddest mother. Their wearied and mystified dialogue comes across like that of parents analysing their troublesome teens at the school gates.

At the centre of the story is the piece of history homework. Smith takes inspiration from something so seemingly uninspiring as a child’s piece of homework and turns it into a story. The report on Mary Queen of Scots becomes analogous to the narrator’s reports on  her/his mother’s sanity, or perceived lack thereof. Just as the narrator pieces together an image of the mother as ‘mad’, so they compile their class notes on Mary Queen of Scots into a report on her execution.

her/his mother’s sanity, or perceived lack thereof. Just as the narrator pieces together an image of the mother as ‘mad’, so they compile their class notes on Mary Queen of Scots into a report on her execution.

In the case of Mary Queen of Scots, the narrator’s chief concern is for the external: the queen’s fashion taste, the embarrassment she must have felt in taking her clothes off to reveal bright red underwear, and the shock to onlookers that what they’d thought was her beautiful hair was in fact a wig, covering a grey beyond. Once more, the thoughts of appearance in the eyes of others takes precedence over the subject’s internal mental state. Perhaps this emphasis on appearance is one thing that is telling of an adolescent’s point of view. Both of the mother’s and Mary Queen of Scots’ stories are told in a detached tone and using unemotional language. So, if we’re to refer back to the title, is this to be read as the narrator’s attempt to write according to the conventions of a history text?

In other works, Smith has excelled in creating astoundingly believable adolescent voices. Astrid in The Accidental, though written in third-person narration, is entirely convincing in her twelve-year-old whims and fervours. In ‘The History of History’, the representation of adolescence is more complex, but just as alluring. This is an adolescence that shields itself behind carefully chosen and learned words of maturity, one that uses matter-of-fact and distanced language to deny itself and to act the grown-up. If other British teenagers today refer to their mothers as ‘Mother’, they’re a rarity; ‘Mum’ tends to meet the requirements. Whether or not the mother, Margaret, is going through a period of anxiety, or even madness, the changes in her outward behaviour perplex the young narrator. Embarrassment at the hands of eccentric parents is a concern that ranks up there with homework and tea, and this gives the narrator reason to react by assuming a position of superiority and treating their mother in their history-homework tone of voice.

In the end, though, in spite of all the teenager’s airs of superiority and expressions of maturity, it is revealed that the narrator doesn’t know how to operate a washing machine. This reminder, at the close of the story, shows us the character behind the narrative voice – a powerless child. It really impresses on us Smith’s capacity for clever manipulation of the styles and conventions of language, even if she keeps us on unremarkable ground.

I enjoyed this write-up so much! Thank you!