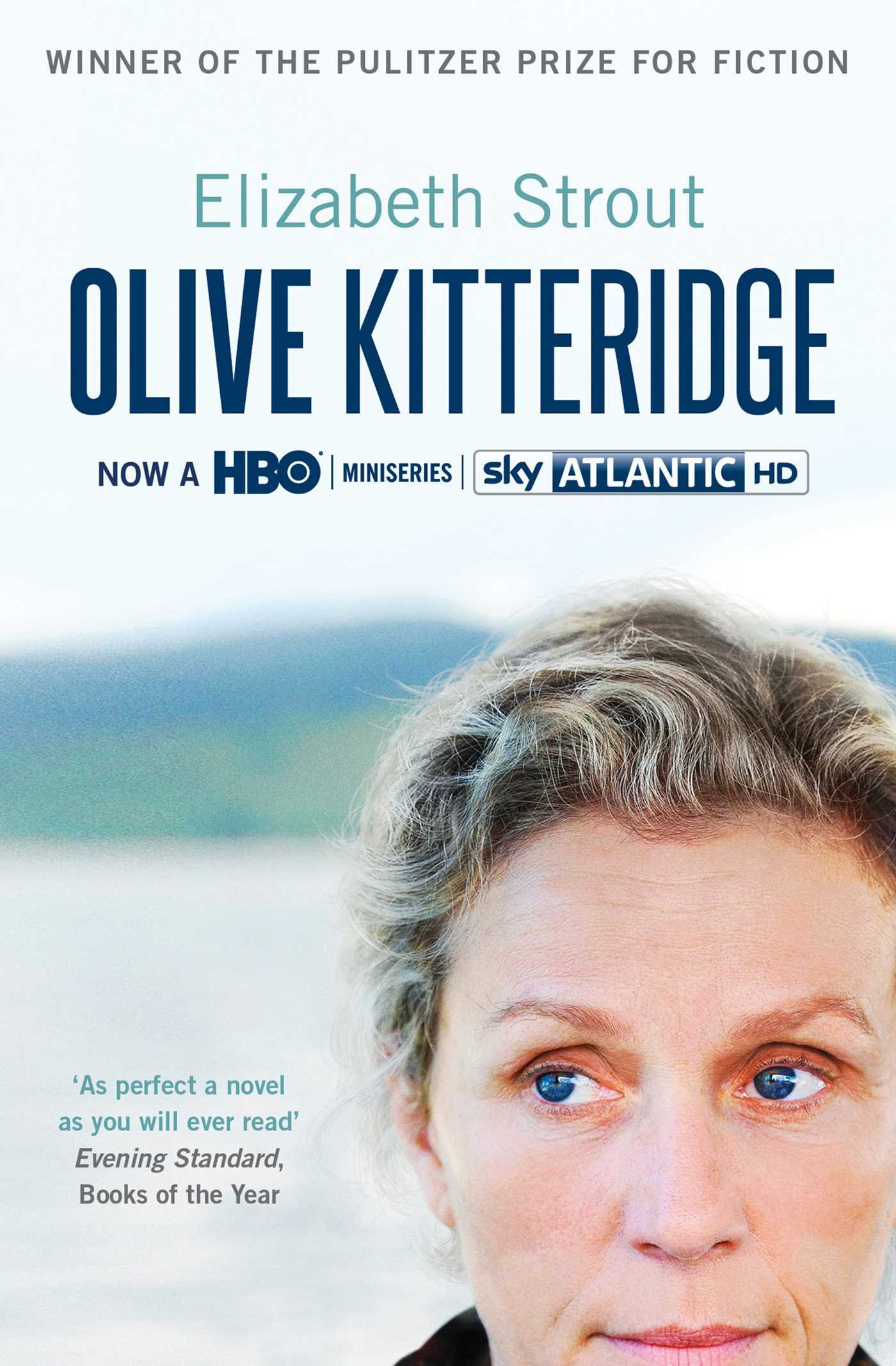

photo © Lena Vasiljeva, 2013

by Erinna Mettler

Olive Kitteridge is a monster. That’s what you’d think from her first appearance in Elizabeth Strout’s 2009 Pulitzer Prize-winning Olive Kitteridge: A Novel in Stories. But Olive is a character of real substance, the heart of the stories, and the reason why this book is particularly loved by writers – many of my colleagues put it in their all time top ten reads.

We know Olive is a monster from the moment she is introduced to us in Chapter One – ‘Pharmacy’ – dismissing other characters with snap judgements, berating her husband and son, and subjecting her guests to the most grudging dinner party possible. Then, when her mild-mannered husband, Henry, asks her if she will come to church, she really lets rip and the result is both funny and terrifying:

“Yes it most certainly too goddamn much to ask!” Olive had almost spit, her fury’s door flung open. “You have no idea how tired I am, teaching all day, going to foolish meetings where the goddamn principle is a moron! Shopping. Cooking. Ironing. Laundry. Doing Christopher’s homework with him! And you –. You. Mr. Head Deacon Claptrap Nice Guy, expect me to give up my Sunday mornings and go sit with a bunch of snot-wots!”

The chapter is narrated by Henry, and, despite her rant about church and her being the titular character, Olive barely gets a look in. This opening story is about Henry’s unrequited love for mousy co-worker Denise Thibodeau. In fact, the story is as much about Denise as it is Henry. What it isn’t about is Olive. She serves only as motivation for others actions. Strout gives a very negative impression of Olive: tetchy, dissatisfied, an overweight bully who terrorises her husband and son. We want Henry to leave her, to live happily ever after with Denise. But our desires are thwarted.

In the second story/chapter, ‘Incoming Tide’, Strout places Olive more in the foreground, though this story isn’t really about her either. Her former pupil, Kevin, sits in a hire car on the quay watching the comings and goings as he prepares his troubled soul for the suicide he has come home to commit. Olive bustles her way into his car and his plans. He imagines her as an elephant in a dress, as she unselfconsciously blows her nose and assails him with questions and knowledge. In this story, Olive first comes across as a gossip, further proof of the questionable character established in the first chapter.

“Jesus,” Kevin said quietly. “Does everybody know everything?”

“Oh, sure,” she said. “What else is there to do?”

As their conversation progresses, however, we begin to see Olive in a different light. Kevin liked her as a teacher and she sets about talking him out of killing himself in a  subtle and careful manner. She knows not to spook him; she is very much aware of what is at stake.

subtle and careful manner. She knows not to spook him; she is very much aware of what is at stake.

Suicide permeates the book, starting with Olive’s father and Kevin’s mother. The conversation Olive and Kevin have here, about their respective parents, is without doubt one of the reasons Kevin rediscovers the will to live. We learn later that, just before her father died, Olive said to him, “Oh Father, everyone gets a little blue.” The wrong thing to say, as it turns out.

When we read these words towards the end of the book, we remember Olive’s conversation with Kevin and how she had it in mind to rescue him. Kevin doesn’t kill himself, instead, egged on by Olive, he saves a woman from drowning and in so doing is himself saved.

‘Incoming Tide’, like ‘Pharmacy’ before it, is self-contained. You could read it in a journal and not guess it was part of a novel in stories. But when you combine the two tales, and the judgements you made about Olive in the first story, each story becomes something bigger than itself. The Olive who inhabited ‘Pharmacy’ would have said: ‘If he wants to kill himself let him and good riddance!’ But the Olive of ‘Incoming Tide’ has compassion and a troubled past. We begin to wonder if our original judgement was justified, if perhaps there is more to her than meets the eye. This interplay is what separates Olive Kitteridge from other collections.

The book progresses in much the same way: each conclusion we come to is challenged by the following chapter. Olive becomes less monstrous and then more so, then less so again. She cries about a teenage girl with anorexia who she barely knows and then, in a truly jaw-dropping incident, she steals her new daughter-in-law’s shoe and vandalises her clothing because of something she overhears at the wedding party. Her character rises and falls like the tide on the shores of Strout’s fictional seaside town. We experience empathy, disgust, laughter, shock and pity, depending on Olive’s actions and words, just like we do in our real life relationships.

Sometimes Olive is only mentioned in a story in passing and, for me, these stories are not as engaging as those in which she is fully present. But, in a way, her absence makes the stories more realistic – she is still in our minds, becoming present in her absence, and we are left to guess at what she is up to.

The stories follow chronologically, but they also have a passage of time within them that can last from hours to decades. They contain memories and hopes; they veer off suddenly on tangents into other places and other people’s lives. You could argue that the natural way of experiencing the world is akin to the short story form – none of our experience comes to us in a long, narrative flow as it does in most novels. Life itself is a series of short bursts, some of which are deeply connected and some only connected by the individual living through them. We accumulate knowledge and experience as we live, which changes the way we perceive our past. Perhaps this is what Elizabeth Strout hoped to draw our attention to through the seemingly disparate stories in the life of one ordinary individual. She has, quite possibly, deliberately chosen to create her novel from short stories because that structure is closest to actual human experience. When I wrote  my own long form fiction, I chose to do so using this structure. It came naturally to me, almost unconsciously, because that is the way life comes at you – not in a single chain of events but in a cyclone of information and impression.

my own long form fiction, I chose to do so using this structure. It came naturally to me, almost unconsciously, because that is the way life comes at you – not in a single chain of events but in a cyclone of information and impression.

On the other hand, maybe Olive Kitteridge was marketed as a novel in stories because many contemporary publishers seem to be worried of short story collections under performing. Perhaps the ‘novel in stories’ genre – seen in Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad, David Mittchel’s Cloud Atlas, Junot Diaz’s This Is How You Lose Her – offers a more viable way through to the novel-reading audience.

If you want to know what Olive Kitteridge would be like if it had been written as a traditional novel, you need look no further than the HBO mini-series. The adaptation dispensed with non-linearity and the stories more concerned with other characters. Instead, it gives us Olive’s life in chronological order and she is present in almost every scene. It is well acted, but it isn’t as satisfying as the book because it spoon feeds us the story, leaving nothing to our imaginations. The beauty of the novel in stories format is that involves a reader as much as they wish. Each story can be read as a single entity, or connections can be made between characters as you move through the book, or you can actively search out connections, join the dots yourself.

Strout makes it that the book mirrors the reader’s experience, as Olive interacts with other characters. Both she and the reader come to conclusions about the inhabitants of the pages through assumption, connection and guess work. So, when Olive and her son discuss a potential date, we recognise our own preconceptions:

“Daddy knew him?” Chris said. “You never told me that.”

“Not knew him knew him,” Olive retorted. “Just knew him from afar. Enough to know he was a nitwit.”

Strout’s readers have almost as much to do with the creation of these stories as she does: they are, in a sense, her co-conspirators. What is left out is as important as what is said, as this is what fires our imagination. The novel in stories format leaves more out than any other literary form and that, for me, is what makes it so compelling.

~

photo of Elizabeth Strout © Leonard-Cendamo