photo by JasonLangheine

by Patricia Duffaud

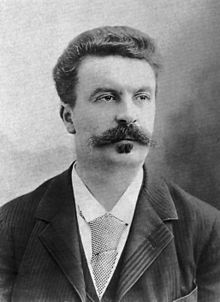

Guy de Maupassant was of course a master of the short story form, and each one of his stories shines still, a finely crafted jewel. ‘Boule de Suif’ is his most famous story and probably my favourite. But one Maupassant story I have never been able to forget is ‘A Mother of Monsters’. It is very nearly a horror story; I was twelve when I first read it and, at that age, it was the most shocking thing I’d come across.

The story is told by a man walking along the seafront. Something causes him to remember a visit, years before, to a friend in the countryside. Maupassant’s narrators often have such friends: a welcoming, provincial man, say, who invites the narrator for a pleasant stay. They might have a copious, uneventful lunch. But at the end of that lunch, when they’re smoking their pipes, the good friend will tell an incredible, shocking, or unearthly anecdote.

In ‘A Mother of Monsters’, the friend goes to a lot of trouble to entertain his visitor, pointing out each one of the village’s attractions. He is genuinely concerned when he runs out of sights to show him; he would so like his guest to have a wonderful time.

Luckily, he remembers ‘the mother of monsters’. This woman is a local curiosity – the villagers call her a devil. She gives birth to deformed babies and sells them to travelling freak shows.

The narrator and his friend walk to the woman’s house. She is a large-boned, healthy creature, who is ‘half-animal, and half woman’. Later, when his friend explains that she gives birth to deformed children on purpose by wearing constrictive corsets during pregnancy, she becomes a ‘brute’.

The narrator and his friend walk to the woman’s house. She is a large-boned, healthy creature, who is ‘half-animal, and half woman’. Later, when his friend explains that she gives birth to deformed children on purpose by wearing constrictive corsets during pregnancy, she becomes a ‘brute’.

The perceived cunning of the peasantry often comes up in Maupassant. His peasants know the value of things and they bargain hard; the women will do anything for money – young girls let men touch them in exchange of a free ride to the market, and their mothers approve. In ‘A Mother of Monsters’, the woman has haggled so well with the travelling showmen that they pay her a yearly rental fee for each one of her eleven children.

There is a concise quality to Maupassant’s writing that propels his stories forward. His use of short sentences, as the two men visit the mother of monsters, propels us into the scene:

He took me into one of the suburbs. The woman lived in a pretty little house by the side of the road. It was attractive and well kept. The garden was filled with fragrant flowers. One might have supposed it to be the residence of a retired lawyer.

This description of the woman’s pretty house makes her story all the more shocking. We can clearly see that she has become so rich from selling her deformed children that her lifestyle is similar to that of a bourgeois.

Later, in a similarly concise manner, Maupassant doesn’t show us the monstrous children – but we hear one of them ‘mew’. The inhuman sound coming from behind a door is enough to chill the reader.

His limpid style and its lack of embellishment was an early stylistic influence on my own writing. Maupassant shows how every word of a short story counts; there is little space for verbal clutter, no matter how beautiful the words might be. Also, many of his tales are written in the first person. His narrators come from comfortable backgrounds but something causes them to internalise the sadness and  horrors they come across. They are not just relating an anecdote; their tale is far more personal. They are recounting a moment that has affected their life in some way, or brought about a realisation that has made them pessimistic, or has confirmed their disenchantment with the world.

horrors they come across. They are not just relating an anecdote; their tale is far more personal. They are recounting a moment that has affected their life in some way, or brought about a realisation that has made them pessimistic, or has confirmed their disenchantment with the world.

In ‘A Mother of Monsters’, the narrator’s friends are far more relaxed than he is. The host takes the narrator to gape at the mother of monsters. For the host, this woman is an afterthought, an oddity that will entertain his visitor, but the narrator is more affected. He feels a ‘profound disgust’, a ‘feeling of rage, of regret, to think that I had not strangled this brute when I had the opportunity’.

The ending goes further and turns this exquisitely crafted tale into an enduring one… Years later, we find the narrator walking on the beach of a fashionable resort with a friend – a physician, this time. They nod at a Parisian woman, a fine, charming beauty surrounded by admiring men. The friends walk on, arm in arm. Further along they come across a nanny watching over three crippled, ‘hideous’ children. The physician explains that these children belong to the beautiful lady they have just passed. The narrator is full of pity. The physician says:

“Do not pity her, my friend. Pity the poor children […] This is the consequence of preserving a slender figure up to the last. These little deformities were made by the corset. She knows very well that she is risking her life at that game. But what does she care, as long as she can be beautiful and have admirers!”

Here we see something of the nuance of Maupassant. Where the peasant woman craved money, the dainty lady was driven by vanity. Just like that, the writer erases the differences between the robust ‘animal’ and the ‘elegant woman’.

The narrator sees through to the truth of it, and in his recounting we feel that he will be left with the burden of the twin stories. His friends will go on as before, oblivious. But the narrator is wiser.

Like his narrators, Maupassant wanted to experience life, and to set himself apart from the rich and the privileged. His narrators are often both brave and reckless in their search for the truth – for that clear-eyed understanding of what lies behind life’s closed doors and facades.