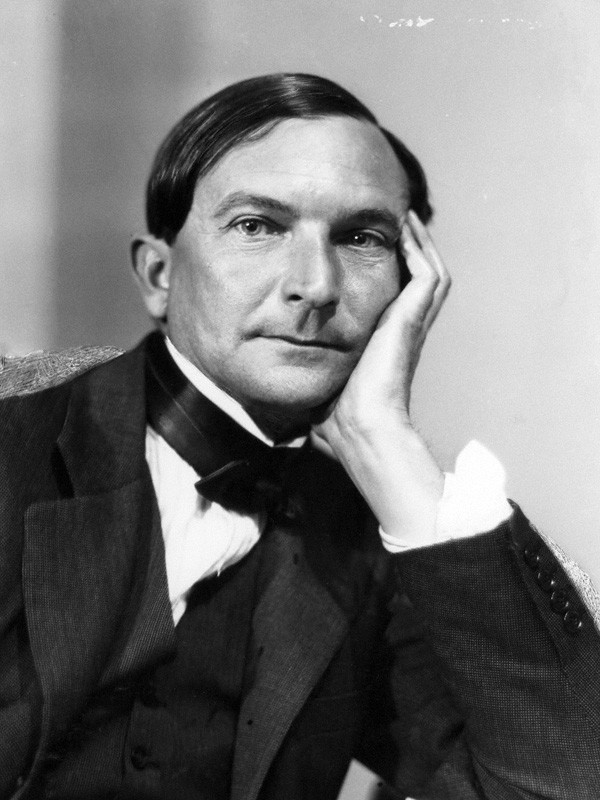

photo © Callum Baker, 2011

by Mike Smith

I recognise something going on in Aumonier’s short stories: in the couple of dozen I’ve read, there seems often to be an attempt to solve a problem of ‘telling’. In particular, I saw it in ‘A Man of Letters’. This is what might be called an epistolary story: one constructed out of letters. It’s a form associated with the novel, and can produce a very tedious story if not handled well.

Aumonier’s handling, though, is deft. He sets himself a difficult task, because his eponymous hero is a working class chap with atrocious spelling and a weak grasp on language. The conundrum is: how to present this hero without sending him up? Aumonier is a comic writer, but our laughter must be sympathetic. We are not to laugh at Alf Codling, but at his situation. ‘When you was on sentry go in the dessert at night it was so quiet and missterius.’

Intentional misspellings in English literature go back a long way – consider Mrs Malaprop, who bequeathed her name to what has become a literary technique – as do depictions of uneducated people butchering language. Shakespeare could give us a laugh at characters like the drunk door-keeper in Macbeth, or the rustic thespians in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but he also put profound thoughts into their, and our, seemingly shallow heads.

Alf’s first letter opens with some poor English, but, piquing the difference between form and content – something that should interest us as writers of fiction – what the words are about eclipses how they are used: ‘My Dear Annie, I got into an awful funny mood lately.’ He tells her that she’ll think him ‘barmy’, but will we? ‘It started I think when I was in Egypt. Nearly all us chaps who was out there felt it a bit.’

The chaps who had been ‘out there’ – in World War One – will have been among Aumonier’s readers, I suspect, and even those of us who were not might have an inkling of what he is recalling. A few missing commas, a verb-subject mismatch and a questionable pronoun do not a moron make.

Aumonier is not seeking to ridicule his character, but to show him writing conversationally, and therefore as a normal, rather than a formal, person. He is also showing his character’s struggle with his own awareness, of himself and of the world around him: uneducated he might be, but self-educating he most certainly is. ‘I want to be good for you and I want to know all about things and that.’

If ‘things and that’ is shorthand for all that we do not yet have the words for, then here is a serious aspiration, comically expressed, and look at his motivation. He wishes to better himself, not for simple self-improvement, but for ‘you’.

The opening line of the second letter, addressed to James Weeks, who runs the local literary society, offers another opportunity for comedy. It is a comedy that could satirise either reader or writer, and, in fact, satirises both: ‘Someone tells me you are a littery society.’ How Weeks  responds to this will reveal him as clearly as Alf’s letter has revealedits author. The story has a short cadenza here, for Weeks is away, and the letter must be passed on – as Alf is informed in a rather pompous note from Week’s secretary. This serves to raise our expectation of how his query will be treated, but before that we must get a reply from Annie.

responds to this will reveal him as clearly as Alf’s letter has revealedits author. The story has a short cadenza here, for Weeks is away, and the letter must be passed on – as Alf is informed in a rather pompous note from Week’s secretary. This serves to raise our expectation of how his query will be treated, but before that we must get a reply from Annie.

That the story is about Alf and his attempts to educate himself, and to deal with his desert experiences, should not distract us from the fact that it is also a story about the relationship between Alf and Annie. After all, it is ‘to be good for you’ that he wants to become more fully himself.

Annie’s letter gives us the context for his aspiration. She is no upwardly mobile snob seeking to aspirate his haitches and to eradicate his accent. ‘My Dear Alf, You are a dear old funny old bean … I can lend you some books. Cook is a great reader.’ Her English is no better than his, but her thoughts are simpler, and more accepting, but then she has not been alone in the desert, and at war. She wants to help, yet her grasp of what he is looking for is weak.

She mentions a couple of (presumably) light novelists – Ethell M Dell and Charles Garvice – which go in stark contrast to the list that Weeks hits Alf with a little later in the tale: Jevons’ Primer of Logic, Welton’s Manual of Logic, Brackenbury’s Primer of Psychology, and the list goes on… By the time we get to Weeks’ list, however, we are fairly sure that Weeks, far from ridiculing Alf by the suggestion, is genuinely trying to help him: ‘Do not be discouraged!’ he writes.

In fact, Weeks is an important character in this story. He represents not only the ‘littery society’ in particular, but that wider literary society that those of us who read – and write – belong to. His reaction to Alf is critical to what sort of story this is, and who and what it is about.

His first response to Alf is as formal as his secretary’s has been, asking for ‘qualifications’, which, by this part of the story, we are sure that Alf does not have. Aumonier is testing our prejudices here, and perhaps our character too. We have the chance to laugh maliciously, if we wish.

Weeks receives a reply that reveals Alf more fully to him: ‘I am not what you might call a littery or eddicated man at all.’ But in the same letter, Alf reveals what he has already told to Annie and he makes a suggestion to Weeks: ‘Perhaps sir you have to have been throw it if you know what I mean.’

And Weeks, perhaps does know, for he writes inviting Alf to join, and then goes about finding a seconder for the proposed membership. Here is the first opportunity for Aumonier to show us Weeks from another angle, that which he shows to his friend Samuel Childers: ‘He sounds the kind of person who would make a splendid foil to old Baldwin with his tortuous metaphysics.’

This equivocal reply raises the story from a level at which it might have operated: there is an ambiguity here about just how sincere Weeks is in his acceptance. To what extent has he understood and respected Alf? To what extent does he see him as an amusing goad to a pompous fellow member? The ambiguity allows Weeks too, to be taken on a journey of self-discovery and perhaps of self-improvement. Depending on our perceptions and our points of view, it is a journey on which we might accompany him.

Childers, in his written reply thinks Weeks means ‘it as a joke’. Weeks, we shall discover, is better than that, though.

Annie, however, is nearer to Childers. She thinks that Alf does not need to change, fearing perhaps that he will move away from her if he does. ‘I shouldn’t think the littery society much cop myself.’

The letters pass between Annie and Alf, and between Alf and the organiser of the Society, and between the organiser and various members. There are so many possible stereotypical ambushes here, but Aumonier avoids them all, for it is not merely a matter of him bashing one class of person or another (with one possible exception that I shall note later). He is creating individuals in a feasible situation, who have ‘expected’ attitudes, but who do not become caricatures.

Weeks’ letter to Childers has been unambiguous: ‘We must certainly get Alfred Codling into our society.’ He is no fool. He knows that Alf is uneducated and inarticulate, and he does have an agenda, but it is not to make a fool of him. Alf goes along, hopelessly out of his depth. Weeks lends him books, and the evening comes when Baldwin delivers a paper. Alf cannot contain himself when Baldwin begins ‘droning forth platitudes and half-baked sophistrie’, and he exclaims: “talk, talk, that’s all it is. There’s nothing in it at all.” Having ‘insulted’ Baldwin, Alf leaves the meeting, as we see in a letter from Weeks to Childers: ‘To my amazement my ex-lance-corporal rose heavily to his feet. His face was brick red and his eyes glowed with anger.’

The Society disintegrates in the aftermath of this event, as letters pass between the insulted, the outraged and Weeks and his ally. And all this is expressed in the letters!

A letter from Childers’ daughter to a friend allows an oblique look at the situation, and at Alf: ‘I have been to two of the meetings especially to observe the mechanic with the soul. He is really quite a dear.’ That her comic quip – ‘the mechanic with the soul’ – is, on another level, an exact description of Alf, and not at all comic, should not be lost on us: comic irony with serious intent.

One letter in particular is crucial, both to the story and to our acceptance of the story, and that is the one in which Alf explains to Weeks why he was so rude. I think it’s rather a masterpiece of writing, because within it, using Alf’s still inarticulate and uneducated voice, Aumonier manages to explain Alf’s epiphany in the desert:

You think of the other fellow over there whose thinkin like you are perhaps and he all alone to lookin up the blinkin stars and it comes over you that its only love that holds us all together love and nothing else at all.

Weeks, whom it would have been so easy to pass off as a bigoted abuser of Alf, is presented as a man of understanding and true education. His resignation precipitates the disintegration of the group, but he resigns in support of Alf’s action and continues to support his protégé in other ways.

Aumonier is a comic writer, and one with a light touch. None of these characters are stereotypes, except perhaps for the villain Baldwin. His letter to Weeks, complaining about the acceptance of Alf into the group, puts forward some arguments about literature and what it means to us as individuals and in the wider society:

…he may be a very good young man in his place. But why join a literary society? Surely we want to raise the intellectual standard of the society, not lower it?

The club secretary, writing to Baldwin, supports these opinions: ‘We might as well admit agricultural labourers, burglars, grooms and barmaids, and the derelicts of the town.’

Baldwin, in his letter of resignation late in the story, includes an OBE in his signature. This is something that Aumonier, we must remember, has awarded him, and in so doing he has also awarded that medal – and the establishment it implies – a character like Baldwin. But the key to this story is that the ‘intellectual standard’ is raised not by Baldwin’s glib articulation of ‘tortuous metaphysics’, but by Alf, as he strives to articulate his epiphany in the desert.

Alf’s journey leads to Annie returning her engagement ring – by letter, of course – with the comment that ‘a book lowse is worse than no good’. This, in turn, leads to a tearful meeting between the two, in which they reunite. This meeting is witnessed by Weeks and he writes a brief account of it in his letter to Childers. When Alf resigns from the society, Weeks does not sever their connection, but develops it further. He sends Alf fifty pounds – a considerable amount in those days – to help furnish his and Annie’s new marital home, and encourages him to continue to borrow books: ‘I was to go on readin the books he says I shall find good things in them…’

It is a thoughtful story, but its main achievement, from a writing perspective, is the way in which Aumonier expresses a profound experience within the straightjacket of a limited vocabulary, using poor articulation without reducing the protagonist to a pastiche or caricature of himself. What Alf and Annie and Weeks, and all the others, write to each other is what Aumonier is writing to us. Aumonier, I suspect, is one of those writers who recognises that it is worthwhile to remind us that we are, and can be, better than we think. If the few accounts of him I have found are to be believed, this might be the reason for how well this writer was loved as an individual.

~

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions (Unbound Press, 2010), the novella A Penny Spitfire (Pewter Rose 2011), and, in 2012, Talking To Owls (Pewter Rose), a collection of short stories, monologues and flash fictions. In 2009, he received the degree of MLitt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator. He is keen on the ‘told’ story, and some of his tellings can be found at BHDandMe on Vimeo. He has a collection of essays on short story form due out from Pewter Rose Press, and a collection of short stories from Sentinel Publications. He is a founder/presenter of LitCaff, a monthly evening of fiction (with added poetry) in Carlisle, England. His most recent collection of short stories is The Man Who Found A Barrel Full of Beer, written as Brindley Hallam Dennis. His collection of essays on A. E. Coppard, English of the English, features responses to the tales of A. E. Coppard.

Mike Smith writes across a range of genres, including poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Under the name Brindley Hallam Dennis he has published That’s What Ya Get! Kowalski’s Assertions (Unbound Press, 2010), the novella A Penny Spitfire (Pewter Rose 2011), and, in 2012, Talking To Owls (Pewter Rose), a collection of short stories, monologues and flash fictions. In 2009, he received the degree of MLitt from Glasgow University. He currently teaches Creative Writing at Cumbria University. His writing has been published, broadcast and performed, and has won prizes and awards in Scotland and England. He is particularly interested in the structure of short stories, and in the relationship between the story and the narrator. He is keen on the ‘told’ story, and some of his tellings can be found at BHDandMe on Vimeo. He has a collection of essays on short story form due out from Pewter Rose Press, and a collection of short stories from Sentinel Publications. He is a founder/presenter of LitCaff, a monthly evening of fiction (with added poetry) in Carlisle, England. His most recent collection of short stories is The Man Who Found A Barrel Full of Beer, written as Brindley Hallam Dennis. His collection of essays on A. E. Coppard, English of the English, features responses to the tales of A. E. Coppard.