('Lights on the Tree' © Ashley P, 2007)

*

‘A LIGHT FRINGE OF SNOW’:

MELANCHOLY REFLECTION IN ‘THE DEAD’

by DR. CHRIS MACHELL

*

The final piece in James Joyce’s Dubliners, ‘The Dead’, has been described as one of the finest short stories ever written. Set in 1904 Dublin, the story follows Gabriel Conroy as he attends a Christmas party with his wife, Gretta. Juxtaposing the public personas of his characters with their private lives, Joyce depicts life as an accumulation of experience, the depths of which we rarely access. The story’s brilliance lies in the economy of Joyce’s prose – Freddy Malins, for example, is depicted as a harmless old soak, but the obvious embarrassment he causes to his mother speaks of a man worn down and written off by those who tolerate but hardly relish his presence.

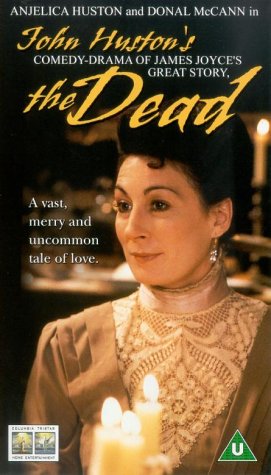

‘The Dead’ was adapted into a feature film by legendary director John Huston in 1987. It was to be Huston’s last film: he was unwell while shooting The Dead and died before it was released. The film has subsequently been overshadowed by his earlier Hollywood pictures, such as The Maltese Falcon, Prizzi’s Honor, and The Treasure of the Sierre Madre. Nevertheless, as both a faithful adaptation of Joyce’s story and a meditation on mortality, The Dead is a fitting coda to a superlative directorial career. Despite receiving critical plaudits at the time of its release, The Dead is little discussed and difficult to track down on DVD (and not even available on Blu-ray), though there is a poignant irony to the way a film about the fading of experience and vitality has itself faded from our collective memory.

‘The Dead’ was adapted into a feature film by legendary director John Huston in 1987. It was to be Huston’s last film: he was unwell while shooting The Dead and died before it was released. The film has subsequently been overshadowed by his earlier Hollywood pictures, such as The Maltese Falcon, Prizzi’s Honor, and The Treasure of the Sierre Madre. Nevertheless, as both a faithful adaptation of Joyce’s story and a meditation on mortality, The Dead is a fitting coda to a superlative directorial career. Despite receiving critical plaudits at the time of its release, The Dead is little discussed and difficult to track down on DVD (and not even available on Blu-ray), though there is a poignant irony to the way a film about the fading of experience and vitality has itself faded from our collective memory.

Gabriel, played by Donal McCann in the film, is due to make a dedication to his hosts, Aunt Julia and Aunt Kate, but worries that his literary allusions will go over the heads of his guests. Meanwhile, his old friend Molly Ivors teases him as a ‘West Briton’ – a slur for Irishmen who admire England too greatly – for writing for the British tabloid the Daily Express. Gabriel maintains his affability yet is clearly uncomfortable, humouring his elderly hosts while taking Molly’s teasing far too personally, and responding irritably when Gretta (Angelica Huston, the director’s daughter and regular collaborator) says she’d like to return to Galway for a holiday.

Gabriel spends the majority of the story wrapped up in himself, completely missing the significance of his wife’s desire to visit Galway. Angelica Huston’s understated performance is one of her best – investing Gretta with a distant melancholy that beautifully brings Joyce’s character to life, made all the more poignant in the near-certainty that this would be the last time she would work with her father.

When Gabriel spots Gretta listening to their friend Bartell D’Arcy singing ‘The Lass of Aughrim’, Joyce describes Gabriel’s arresting vision of his wife:

There was grace and mystery in her attitude as if she were a symbol of something. He asked himself what is a woman standing on the stairs in the shadow, listening to distant music, a symbol of. If he were a painter he would paint her in that attitude. Her blue felt hat would show off the bronze of her hair against the darkness and the dark panels of her skirt would show off the light ones. Distant Music he would call the picture if he were a painter.

Gabriel is struck by his wife’s beauty, and for the first time since the start of the party, is brought out of himself. However, despite Joyce’s beautiful prose, in idealistically imagining how he would paint Gretta, Gabriel fails to connect her attitude to her earlier desire to visit Galway. Later, as they travel to their hotel, he doesn’t understand why she is upset. It is only when Gretta tells him about her love affair with Michael Furey that he is humbled into seeing her as an entire person with an internal life. Gabriel is shaken by the story of Michael Furey’s intense passion for her, not least because he had no idea of that chapter of her life:

So she had had that romance in her life: a man had died for her sake. It hardly pained him now to think how poor a part he, her husband, had played in her life […] Generous tears filled Gabriel’s eyes. He had never felt like that himself towards any woman, but he knew that such a feeling must be love.

The power of Gretta’s story is not in its intensity, but that, by the time she tells Gabriel that Michael’s passion has all but faded to a shade, it is eroded by time. Huston directing his daughter in the film version of this scene is rich in subtext, and the line ‘It hardly pained him now to think how poor a part he … had played in her life’ works metatextually as a bittersweet description of the diminishing roles parents play in their children’s lives.

The power of Gretta’s story is not in its intensity, but that, by the time she tells Gabriel that Michael’s passion has all but faded to a shade, it is eroded by time. Huston directing his daughter in the film version of this scene is rich in subtext, and the line ‘It hardly pained him now to think how poor a part he … had played in her life’ works metatextually as a bittersweet description of the diminishing roles parents play in their children’s lives.

The fluidity of Huston’s camera as it observes the party’s conversations reflects the vitality of the party and its guests. However, as it settles on Gretta she quietly reminisces about Galway. The camera is no longer a passive observer of the party but rather a participant in Gretta’s wistful sadness. Indeed, perhaps the most significant change in the transition of ‘The Dead’ from page to screen is the subtle shift in perspective from Gabriel to Gretta. Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ is told very much as Gabriel’s story, but Huston’s privileging of Gretta’s perspective is subtle yet important. The text remains the same, but the film’s earlier emphasis on Gretta’s sadness surely invites interpretations of Huston’s relationship both with his daughter, and as a reflection of the end of his own career. Joyce’s final words are repeated almost verbatim in the film:

[Gabriel] watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dark, falling obliquely against the lamplight. […] It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. […] His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

Although he was American, Huston had Irish citizenship and famously loved the country. It is surely apt, then, that the words of his final film should have come from one of Ireland’s most renowned writers, but more than that, that those words are a reflection on the inevitable falling of vitality into mortality. One might argue that The Dead has fallen into obscurity for a reason, and certainly Huston’s earlier films have a vigour that his final work lacks. Nevertheless, The Dead works as a tribute to one of Joyce’s most celebrated works, a moving depiction of life’s obscured melancholy, and most powerfully, a final, personal signature marking the end of Huston’s life and career.

~

You can read James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ here on THRESHOLDS.

~

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.

What struck me about the film was the way that Huston couldn’t do any better, or indeed different, than replicate Joyce’s words at the end of the story, especially considering that ‘voice over’ is said to be the death of the visual medium. I thought your point about the shift of emphasis was interesting, bringing home the way the shown story transfers to Huston, who is after all re-telling it, compared with the told one, that was Joyce’s telling, and perhaps related to his fears about Nora B’s past. Thought provoking article.