photo © Micagoto 2011

by K.S. Dearsley

We are the narrators of our own stories. The tales we tell ourselves about who we are construct our identity, they are how we make sense of the world. No wonder that narrators often intrude into novels and stories, inviting readers to see things from their perspective. That’s why would-be writers are inevitably told to show, not tell. Get it right and the narrator recedes into the background, so that there’s nothing to come between the reader and the story. But it isn’t as easy as it sounds.

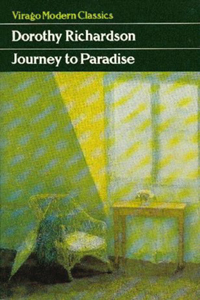

Dorothy Richardson was a pioneer in the use of stream-of-consciousness. The technique is now a convention, but at the time Richardson wrote, this was a radical departure from traditional form. During the heyday of Modernism in the early years of the twentieth century, Richardson was considered one of its leading writers. Virginia Woolf credited Richardson with writing ‘the psychological sentence of the feminine gender’. Her stories ‘Garden’, ‘Visitor’, ‘Visit’, ‘Ordeal’ and ‘Death’ chart inner life from a toddler to old age. They can all be found in the collection Journey to Paradise: Short Stories and Autobiographical Sketches.

The stories weren’t conceived as a series – they appeared between 1919 and 1949 while Richardson was also writing her epic sequence of thirteen novels, Pilgrimage. Although they weren’t written in the age order of the protagonists, they form a birth to death cycle that demonstrates different stages in the struggle each of us undergoes to make sense of the world, and how the split between our inner and outer lives develops.

The stories weren’t conceived as a series – they appeared between 1919 and 1949 while Richardson was also writing her epic sequence of thirteen novels, Pilgrimage. Although they weren’t written in the age order of the protagonists, they form a birth to death cycle that demonstrates different stages in the struggle each of us undergoes to make sense of the world, and how the split between our inner and outer lives develops.

‘Garden’ shows a girl, barely more than a toddler, experiencing the garden of the title. Most authors would probably view the girl from outside, and although they would show us what she did and how she reacted, we would not know how it actually felt to be her. Richardson, however, takes the reader inside the child’s mind. What does go on in toddlers’ heads? They don’t have the language to tell anyone, and by the time they do, they don’t remember. I have no clear recollection of things I felt or experienced as a small child. I recall only that things often seemed simply to happen, or that they were familiar to me. I don’t remember that I didn’t like baked beans, I only know that I didn’t. How hard it must be to write as if you’re a child that age, yet somehow Richardson accomplishes it.

Everything in the little girl’s world is sentient. The flowers ‘were here all the time, happy and good when no one was here’. She doesn’t yet know how to separate the animate from the inanimate, any more than she can separate her senses, so she experiences a kind of synaesthesia, seeing ‘the different smells going up into the sunshine. The sunshine smelt of the flowers’. For her, everything is possible.

A series of unconnected images – ‘raindrops outside the window falling down in front of the dark pointed trees. The snowman alone on the lawn’, ‘shiny apples on the trees’, ‘the slippery swing seat’ – must be memories, but Richardson doesn’t tell us so. Instead, she allows the reader to experience them as fragments flashing through the child’s mind. In the child’s world, there is little cause and effect. She doesn’t relate what she does to what happens, but assigns the agency to external forces: ‘The gravel stopped making its noise when she stood still.’

Details, such as ‘the bent-over body of Minter. The little thrown marrow had hit him. He had not minded’, allow the reader to infer what type of garden it is, the season and the family’s social standing without being told, but none of this information is important. What matters is how it is to be a small child. Without the mediation of an external narrator, I felt an immediate connection with her, and experienced afresh things that I now take for granted.

In ‘Visitor’, the little girl, who may or may not be the same one as in ‘Garden’, is older, but not by much. She is more self-aware, but she still feels ‘the plants and ferns don’t notice her’, and hears ‘loud voices in the hall, sending away the lovely smell from her fingers that had just pinched a leaf of scented geranium’. She knows more about how she’s expected to behave, but hasn’t become so used to convention that she’s stopped using her intuition. When her mother greets their visitor, she hears ‘Mother’s voice like when you are ill, forgetting the garden and telling Aunt Bertha she is a cripple’. She knows, what her mother appears not to, that perception creates reality:

Stupid, stupid Mother. She only knows Aunt Bertha is a cripple. Why can’t she see her, up there, in the text, on the wall? She is spoiling the text, because she can’t see.

By the time the events of ‘Visitor” take place, the little girl is old enough to journey on a train with her little sister, but she still feels that their destination is coming towards them, rather than they travelling towards it. She has learned enough of the world to start judging others. When her sister makes an embarrassing remark she pretends not to hear, and then says, ‘Sh… and feels like Miss Web. Pug is quiet at once. She knows it is rude to make remarks’. As the protagonist grows from ‘Visitor’ to ‘Visit’, the point of view switches more frequently to an external narrator, echoing the girl’s increasing consciousness of the outside world. The division between her inner ‘natural’ self and her outer ‘social’ self is already becoming established, but the flow from internal to external is so subtle that the reader is hardly more aware of it than the little girl.

By the time the events of ‘Visitor” take place, the little girl is old enough to journey on a train with her little sister, but she still feels that their destination is coming towards them, rather than they travelling towards it. She has learned enough of the world to start judging others. When her sister makes an embarrassing remark she pretends not to hear, and then says, ‘Sh… and feels like Miss Web. Pug is quiet at once. She knows it is rude to make remarks’. As the protagonist grows from ‘Visitor’ to ‘Visit’, the point of view switches more frequently to an external narrator, echoing the girl’s increasing consciousness of the outside world. The division between her inner ‘natural’ self and her outer ‘social’ self is already becoming established, but the flow from internal to external is so subtle that the reader is hardly more aware of it than the little girl.

In ‘Ordeal’, the protagonist is an adult woman facing an operation, and the point of view is increasingly external, but the division between her inner and outer world is still blurred. As with ‘Garden’ there is a sense of things happening to the protagonist, Fan, over which she has no control. A narrator tells us how she feels:

Her known self, arrested thus, was making all its statements at once. The most welcome was its cheerfulness, inexplicable and as little expected as the wise-seeming state of composure.

As Fan tries to analyse her feelings, the sentences become more complex. She now uses conventions and etiquette as a defence against her fear. The division between the self she has constructed throughout her life and her infant self breaks down as the anaesthetic takes effect.

Fresh and powerful came the volatile essences, playing in the air before her nostrils like a fountain. Her heart answered, her blood answered; but not herself. Desperately and quite independently her threatened heart fought against this power that was bearing her down. She raised her hands to still it.

“Clasp your hands.”

All of herself was in her clasped hands, beating, throbbing. Less, and less, and… less…

The narrative in ‘Death’, where an elderly woman faces her final hours, is not so much stream-of-consciousness as interior monologue. Unlike the child in ‘Garden’, she can judge her position in the world in relation to others, and can think in language rather than simply feeling things, but her thoughts, as she tries to make sense of life, become increasingly fragmented. ‘See no more. Work no more. Worry no more.’ She observes how she feels, but at last she returns to the beginning of simply being.

Back and back into her own young body, alone. In front of the darkness came the garden, the old garden in April, the crab-apple blossom, all as it was before she began, but brighter…

By the time Richardson was in her eighties and living in a nursing home, her fame had fallen so far that the staff thought she was delusional when she told them about her career. I don’t know how accurately she portrayed the experience of death, any more than I can now recall how it really felt to be a baby or toddler. However, to treat her stories as a cold exercise in style is to miss the delight of seeing the world with fresh eyes that her style makes possible. I think it’s high time Dorothy Richardson was recognised once more as the great story writer that she was.

~

K. S. Dearsley has an MA in Linguistics and Literature, and her stories, flash fiction and poetry have been published on both sides of the Atlantic. Her work is available from Smashwords and Amazon.