photo © Lars Hammar, 2008

by Geoffrey Heptonstall

Jorge Luis Borges may be described sympathetically as a creator of worlds. But his are not the fantasy kingdoms of popular romances. A Borges world is one of paradox and irony. In a few paragraphs, he is able to suggest possibilities that open doors into the infinite. It is a process that has to be experienced in reading. The text is its own world. How can one describe a whole world without recreating that world as an exact replica of the original?

Perhaps the most Borgesian, and most approachable of Borges’ fictions, is ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’. Written in the factual tone of an essay, the story is of a modern writer, Menard, who writes Don Quixote for a modern readership. He does not re-write it: every word is identical to Cervantes. Yet it reads differently because we are not late Renaissance humanists reflecting on the ideals of chivalry that have passed not too long ago. Our conception of history and of truth are grounded in the existential dilemmas generated by scientific rationalism. Words have changed their meaning because we think differently. To write the Quixote now is to write a different book.

He did not want to compose another Quixote – which is easy – but the Quixote itself. Needless to say, he never contemplated a mechanical transcription of the original; he did not propose to copy it. His admirable intention was to produce a few pages which would coincide – word for word and line for line – with those of Miguel de Cervantes.

If, to you, this is merely a clever conceit, an intellectual jeu d’esprit, then Borges is probably not for you. But if the idea intrigues you, and you are charmed by the lightness of touch with which Borges expresses his idea, then you will appreciate his stories. The challenge is both to the intellect and to the sensibility of the reader. The mystery is a reasoned irrationality, if such a concept were possible. In this world it is. A Borges story resembles an essay. A Borges essay is a challenge to the imagination as well as the intellect.

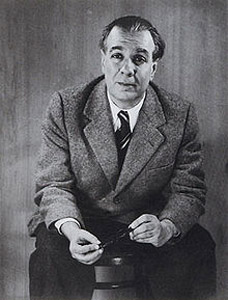

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires in 1899. His death in 1986 meant the passing of the last great writer born in the Nineteenth Century. This is important to our understanding of the man. He was, as we would say, a Victorian. His outlook was old-world, one of courtesy and reticence and this was reflected in his bearing and manner. When acknowledging a television audience’s appreciation, hands on his stick, he turned and gave a gracious bow.

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires in 1899. His death in 1986 meant the passing of the last great writer born in the Nineteenth Century. This is important to our understanding of the man. He was, as we would say, a Victorian. His outlook was old-world, one of courtesy and reticence and this was reflected in his bearing and manner. When acknowledging a television audience’s appreciation, hands on his stick, he turned and gave a gracious bow.

The point is not trivial. Borges’ aesthetic, although Modernist, has a late Victorian sensibility, grounded in the scientific romances of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, and, especially, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh Gothic. Culturally, Borges was multi-lingual and international, although the base was Latin American, which is to say post-colonial Hispanic and New World. Borges met the revolutionary poet Pablo Neruda just once. On most things their outlook differed, but on one thing they did agree: Spanish was less amenable to poetry than English or French. Both men had considered not writing in Spanish, and each, independently, had concluded that, whatever its drawbacks, it was his language, his culture.

With no sympathy for Marxism, however it is articulated, Borges was distanced from many Latin American writers. He gained respect, though, both for his literary achievement and for his staunch resistance to Fascism (and anti-Semitism) in general, and to the dictator Juan Peron in particular. Borges believed in political stability as the founding principle of a modern society; his essential Conservatism generally allied him to democratic principles.

Such lapses are mere shadows of an incandescent vision. In his essay ‘The Argentine Writer and Tradition’, Borges explains his aesthetic. In early stories, later disowned, the young writer tried to evoke the life of Buenos Aires. The response always seemed conventional and inadequate. Then he wrote ‘Death and the Compass’ in 1942, a detective story in which there is also mystery in the metaphysical sense. The clues follow a Kabbalistic pattern – the narrative method plays with time so that a network of illusion and reality confuses the sceptical reader or enchants the sympathetic – a typical Borgesian device. The point was that, in devising a fictive world, Borges found that he had evoked Buenos Aires more effectively than in objective description. He had discovered the use of allusion and irony.

It was only in his later years that Borges acquired a global reputation. When he shared the Prix International literary award with Samuel Beckett in 1961, it was a remarkable breakthrough. Thereafter, he found a responsive audience to his hallucinatory enchantments in the counter-cultural years of the Sixties. Other honours quickly followed, but the process of translating his work was to take time. There was so much. He had been publishing for decades – stories, essays, poetry – gaining a reputation in Latin America but not beyond.

It was only in his later years that Borges acquired a global reputation. When he shared the Prix International literary award with Samuel Beckett in 1961, it was a remarkable breakthrough. Thereafter, he found a responsive audience to his hallucinatory enchantments in the counter-cultural years of the Sixties. Other honours quickly followed, but the process of translating his work was to take time. There was so much. He had been publishing for decades – stories, essays, poetry – gaining a reputation in Latin America but not beyond.

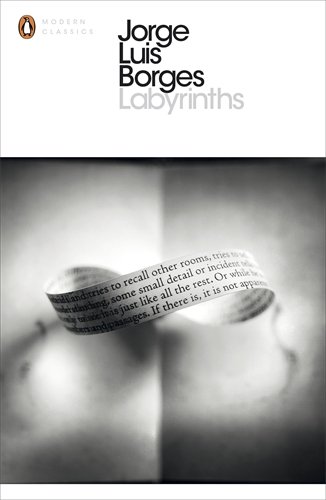

As far as I know, the very first English translation of his work did not appear until 1948, in, of all places, the Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine. It was an ironic beginning for a writer often considered cerebral and remote, an unworldly dreamer. Shortly after the Prix International two important Borges collections, Fictions and Labyrinths, were published in English. Borges had arrived internationally. There followed lecture tours, further publications and honours. The Book of Imaginary Beings, translated to English in 1967, is a bestiary of mythological creatures records, as if making factual the imagined. There is sufficient known truth in A Universal History of Infamy, translated to English in 1972] – Billy the Kid, for example – to fool the reader into accepting all the villains cited as having existed. In the Borges world, imagination and reality are two surfaces of the same canvas.

Much of Borges’ work translated in the Sixties was originally published many years before. It took the world a long time to catch up. The public image of the ethereal dreamer, remote in mind and place, took a jolt from ‘Doctor Brodie’s Report’, published in 1970 and simultaneously translated. These were fictions of Argentine low-life, the knife-fight in the alley, the backstreet bordello, and the erotic violence of the tango. The world received a timely reminder that the cosmopolitan dreamer Borges was very much a writer of a particular culture far removed from Paris or Manhattan.

The tango is perhaps the most Borgesian of dances, stylised, strange, dangerous, just as the labyrinth is the most Borgesian of constructs. Blindness struck Borges at the very time he was becoming a writer who must be read. His own reading became hearing. His writing became speaking. His vision was within. The ironies form a satisfactory conclusion to a consideration of Borges. He is not an easy read, but he is, if appreciated, extraordinarily compelling.

~

Geoffrey Heptonstall writes regularly for The London Magazine and Open Democracy. He has been an adjunct lecturer in Writing at Anglia Ruskin University. Essays and reviews have appeared in publications including Cerise Press, TLS, Wasafiri. Recent publications include three plays: Providence (Lampeter Review for Lampeter University Writing Centre 2013) A Dream of Shangdu (Gold Dust, 2014) and 1915 (Stand Up Tragedy, Edinburgh Festival blog 2015). Recent poetry has appeared in Agenda, The American Aesthetic, International Literary Quarterly, London Progressive Journal and Meniscus. Recent fiction includes performed stories for A Word in Your Ear, Liars’ League and White Rabbit.

Geoffrey Heptonstall writes regularly for The London Magazine and Open Democracy. He has been an adjunct lecturer in Writing at Anglia Ruskin University. Essays and reviews have appeared in publications including Cerise Press, TLS, Wasafiri. Recent publications include three plays: Providence (Lampeter Review for Lampeter University Writing Centre 2013) A Dream of Shangdu (Gold Dust, 2014) and 1915 (Stand Up Tragedy, Edinburgh Festival blog 2015). Recent poetry has appeared in Agenda, The American Aesthetic, International Literary Quarterly, London Progressive Journal and Meniscus. Recent fiction includes performed stories for A Word in Your Ear, Liars’ League and White Rabbit.