photo by Erica Watson

We are delighted to announce that the winner of the

THRESHOLDS International Feature Writing Competition is

Geoff Holder

Comments from the judging panel: ‘an instantly engaging essay’; ‘sharp, rigorous but highly readable’; ‘exquisitely polished’; ‘rich in its use of language’; ‘wonderfully wry and stylish’; ‘expert, nuanced, energetic’; ‘I’ve never been particularly interested in Lovecraft but I certainly am now’.

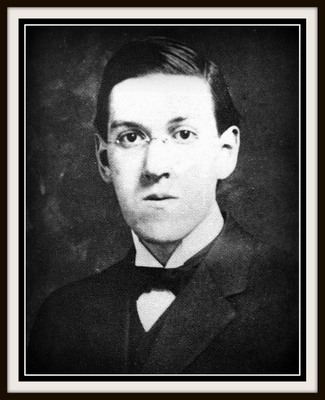

We Recommend: H.P. Lovecraft

by Geoff Holder

To begin with a warning: if you are over 21, it is probably already too late for you.

The delirious imagination of H.P. Lovecraft is best encountered in adolescence, before restrictive notions of good taste and good writing have taken hold. This is not to suggest that Lovecraft is a ‘so bad he’s good writer’ of the ‘outsider art’ genre; that is certainly not the case. But his characters, especially the frowsy narrators in which he specialises, rarely escape two-dimensionality (in contrast to his monsters, which are at home in at least five dimensions); his prose style can seem laboured and gauche; adjectives such as ‘eldritch’ and ‘squamous’ are vigorously spanked to the point of abuse; female characters are largely notable by their absence; and there is an overwhelming sense of closeted, frustrated disgust at the world that may, for some readers, be all too reminiscent of pimple cream and unfettered hormonal urges.

The delirious imagination of H.P. Lovecraft is best encountered in adolescence, before restrictive notions of good taste and good writing have taken hold. This is not to suggest that Lovecraft is a ‘so bad he’s good writer’ of the ‘outsider art’ genre; that is certainly not the case. But his characters, especially the frowsy narrators in which he specialises, rarely escape two-dimensionality (in contrast to his monsters, which are at home in at least five dimensions); his prose style can seem laboured and gauche; adjectives such as ‘eldritch’ and ‘squamous’ are vigorously spanked to the point of abuse; female characters are largely notable by their absence; and there is an overwhelming sense of closeted, frustrated disgust at the world that may, for some readers, be all too reminiscent of pimple cream and unfettered hormonal urges.

Yet despite all this, Howard Philips Lovecraft, the horror-meister of the Jazz Age, retains a hold on the fantastique so tenacious that many readers, once introduced to his peculiar world, never want to leave. Stephen King, T.E.D. Klein, Ramsay Campbell, Neil Gaiman and Clive Barker are frequent visitors to Lovecraft’s realm; there is a long-running Lovecraft joke threaded through the multiple volumes of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series; and Alan Moore – with J.G. Ballard no longer with us, a contender for the title of Greatest Living Englishman – is so obsessed with H.P.L. that his Black Dossier graphic novel contains a pitch-perfect Lovecraft pastiche written in the voice of a Jeeves and Wooster comic adventure.

The reason why Lovecraft’s work transcends its limitations and continues to ping-pong around the collective cerebellum lies in his creation of an alternative mythology that steps aside from the usual dualistic religious preoccupations of the horror genre. Demons, angels, Heaven and Hell – even Christianity itself – are virtually absent in Lovecraft’s otherwise contemporary America. Here, evil is not combated by the flourishing of crosses or the utterance of holy words. Instead, we are introduced to a world in which blinkered humanity is revealed as a bit-player on our own planet, with monstrous, ancient extraterrestrial entities constantly seeking to break through from elsewhere and return to their previous over-lordship as masters of the universe. Lovecraft’s Great Old Ones, with their consonant-heavy names such as Azathoth, Cthulhu, Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep and Shub-Niggurath, are beyond conventional narratives of Good and Evil; they are cosmically indifferent to us. Except, perhaps, when they’re hungry.

Lovecraft died in 1937, in his beloved Providence, Rhode Island. Beset by nightmares, crabbed by genteel poverty and over-sensitive to rejection, he never realised his full potential as a writer. With one minor exception, he was not published in book form during his lifetime. His numerous short stories saw a brief light of day in pulp magazines such as Weird Tales, and would have vanished altogether had not his friend and collaborator August Derleth founded Arkham House in 1939 with a mission statement of publishing Lovecraft in hardcover.

Derleth went on to author many stories based around scribbled fragmentary ideas in Lovecraft’s Commonplace Book, and also codified what he described as the ‘Cthulhu Mythos’ – the alien mythology that acted as an umbrella concept in many of Lovecraft’s tales. Lovecraft himself seems not to have had a coherent take on his own creation, and his stories often contradict each other. Derleth recognised the inherent ‘hook’ of the Mythos as an organising concept – the way its implied existence made readers want to know more about how this universe operated, and to winkle out the complex relationships between the Great Old Ones, the crypto-history of humanity, and the many magical books mentioned in the form of casual throwaway lines. Indeed, when Lovecraft’s infelicitous prose and cardboard characters are long forgotten, it is the mordant tapestry of alien gods striving to come through that lingers in the mind.

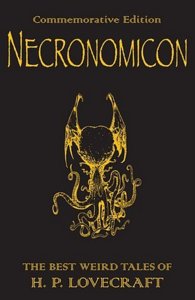

The classic route for this alien infiltration is via the pages of The Necronomicon. The ‘Book of Dead Names’ is supposedly an ancient grimoire, its pages infused with pre-human incantations designed to bring the Great Old Ones through. Lovecraft’s characters are frequently to be found reading aloud from the forbidden volume, thus willingly or inadvertently opening the portal to distressingly voracious entities in full interstellar overdrive. Lovecraft often discussed the book in the context of other, genuine grimoires, and threaded mentions of it through the stories he ghost-wrote or ghost-edited for other writers of weird fiction in his circle. As a result The Necronomicon became first an object of interest, and then an object of desire. Lovecraft was soon fielding the first of many enquirers keen to know where they could acquire a copy.

The Necronomicon was an entirely fictitious book. Nonetheless, I own three different versions of it, all claiming to be the genuine article. Even stranger, some occultists have claimed to have made use of The Necronomicon to perform rituals, and even to have successfully made magical contact with the Great Old Ones. Quite why anyone would want to add to their social network a set of cosmic chaos creatures dedicated to the eradication of humanity is beyond me. This might be the barmiest testimony to the enduring power of Lovecraft’s fiction – many writers’ characters become ‘real’ for their readers, but not usually in the form of destructive extraterrestrial entities made physically manifest.

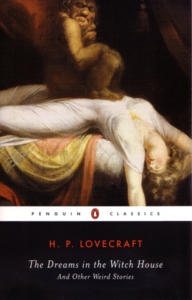

Lovecraft’s stories and short novels have been collected, re-collected, dismembered and put back together in different arrangements so many times that there is no one definitive anthology, although the trio of volumes edited for Penguin by the premier Lovecraft scholar S.T. Joshi in 2002 are the best place to start: The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories, and The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories. There are too many other published variants to list.

Once you plunge in, you will swiftly discover that not all of Lovecraft’s stories feature his famous alien/monster cosmology. Lovecraft himself was ambivalent about the value of his Great Old Ones project – the work that actually makes him original – and so his style swept across the gamut of supernatural and fantasy literature as it existed up until the 1930s. You will find tales aping the florid whimsicalities of Lord Dunsany (‘The White Ship’), or under the influence of Poe, M.R. James or Ambrose Bierce (‘Facts Concerning the Late Arthur Jermyn and His Family’, ‘The Tomb’, ‘The Rats in the Walls’). There are communications from the dead, visitations from witches’ familiars, and grim deeds in shuttered rooms: Gothic fancies filtered through a distorted New England lens. Their quality varies extravagantly, and although the very best have the oneiric atmosphere of a morbid hallucination, they are not what makes Lovecraft special.

For that, we have to turn to works such as ‘The Call of Cthulhu’. The opening paragraph could also act as an introduction to the Mythos:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant what we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, has hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Cthulhu has become the poster-monster for Lovecraft’s wide-screen cosmic theme – the Lovecraft ‘brand name’, if you will. (A cartoon widely available on the internet shows Cthulhu as an American Presidential candidate. The slogan reads: ‘Vote Cthulhu. Why choose the lesser evil?’) A god-like entity originating from the stars or another dimension, Cthulhu is trapped, its life extinguished, deep beneath the ocean, but subject to the enigmatic prophecy: ‘That is not dead which can eternal lie. And with strange aeons even death may die’. The monstrosity announces its return from death by projecting dreams into the minds of humans, especially ‘genetically degenerate’ people whose ancestors either used to worship the beast, or mated with Cthulhu’s hideous oceanic offspring. Told you issues of good taste would arise.

The narrative employs a structure that would later be used to powerful effect in films of the fantastique such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Weird things happen around the world – in this case, dream-driven sculptors and painters produce bizarre works, an Eskimo cult worship a bloodthirsty deity, and a sailor in the Pacific is driven mad by something he witnesses. Slowly, the narrator realizes that all these are signs and wonders: something is coming. And that something is a titanic dragonesque thanatophile with a head made of tentacles. Eldritch and squamous, indeed.

By the end of the tale Cthulhu has been banished once more to its underwater city of R’lyeh, and the apocalypse narrowly averted. This is a fairly typical result: the Great Old Ones are occasionally stymied in their quest for dimensional lebensraum; but they are rarely totally defeated, meaning they are always out there, waiting for the next opportunity to break through.

To anyone familiar with the genre, the themes may even seem over-familiar – but that is only because horror and fantasy works have been feeding off Lovecraft for decades. His work has influenced filmmakers and writers who have never even read him.

‘The Call of Cthulhu’, written in 1926, some nine years into what might tenuously be termed  Lovecraft’s writing ‘career’, was the first of his stories to feature what posterity has regarded as his signature theme. Strangely enough, only around fifteen per cent of Lovecraft’s total output falls under the ‘Cthulhu Mythos’ rubric. The telling titles include ‘The Dunwich Horror’, ‘The Shadow Out Of Time’, ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’, ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’, ‘At the Mountains of Madness’, and ‘Haunter of the Dark’. They circulate around fictional New England towns – Dunwich, evoked by the real-life English village in Norfolk that has been eroded by the sea; Innsmouth, home to a hybrid human race with a distinctly fishy look; and Arkham, after which August Derleth’s Arkham House was named. A copy of The Necronomicon can be found in a restricted room in Arkham’s Miskatonic University, and in ‘The Dunwich Horror’ it is directly responsible for a human woman giving birth to monstrous (and even transdimensional) offspring fathered by Yog-Sothoth.

Lovecraft’s writing ‘career’, was the first of his stories to feature what posterity has regarded as his signature theme. Strangely enough, only around fifteen per cent of Lovecraft’s total output falls under the ‘Cthulhu Mythos’ rubric. The telling titles include ‘The Dunwich Horror’, ‘The Shadow Out Of Time’, ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’, ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’, ‘At the Mountains of Madness’, and ‘Haunter of the Dark’. They circulate around fictional New England towns – Dunwich, evoked by the real-life English village in Norfolk that has been eroded by the sea; Innsmouth, home to a hybrid human race with a distinctly fishy look; and Arkham, after which August Derleth’s Arkham House was named. A copy of The Necronomicon can be found in a restricted room in Arkham’s Miskatonic University, and in ‘The Dunwich Horror’ it is directly responsible for a human woman giving birth to monstrous (and even transdimensional) offspring fathered by Yog-Sothoth.

If all this strikes you as slightly preposterous, well, it is. That is often the nature of genre fiction, even in the hands of a canonical writer, which is what the lantern-jawed sage of Providence has become. Preposterousness is part of the point. And when I sit at my desk, with its six-inch-high (1:1000 scale) model of Cthulhu, and put The H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society’s jokily perverse Christmas carol album on the CD player (‘The Great Old Ones are Coming to Town’, ‘It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Fish-Men’, ‘I Saw Mommy Kissing Yog-Sothoth’), and re-read the stories that enthralled my perfervid teenage imagination – well, the potency is still tangible. These are tales, often inspired by nightmares, which will continue to work through your dreams long after you have finished reading. Encountering Lovecraft for the first time may smell like teen spirit; but the odour can last a lifetime.

~

Geoff Holder is the author of 24 non-fiction books on the strange and the supernatural and the Gothic and the gruesome. The latest of these is Paranormal Cumbria (The History Press, 2012). He lives in Scotland and manifests mysteriously at www.geoffholder.com.

Geoff Holder is the author of 24 non-fiction books on the strange and the supernatural and the Gothic and the gruesome. The latest of these is Paranormal Cumbria (The History Press, 2012). He lives in Scotland and manifests mysteriously at www.geoffholder.com.

Brilliant piece! Congratulations on winning the contest. I have to confess that I’ve never read his works — at least I don’t think so — but will have to investigate further. I think I saw the “Dunwich Horror” on TV if I’m not mistaken. I do love Edgar Allen Poe but Poe’s characters were never like this:

“Great Old Ones, with their consonant-heavy names such as Azathoth, Cthulhu, Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep and Shub-Niggurath, are beyond conventional narratives of Good and Evil; they are cosmically indifferent to us. Except, perhaps, when they’re hungry. ”

Best,

Dora

Bugger. Being well over 21, I now realise why a brief attempt to read Lovecraft in my 30s resulted in yawnsomeness. But this piece of writing makes me want to go back and give him another go. Cheers GH.