photo by Mathieu Degrotte

The Value of Dead End Jobs in

Raymond Carver’s ‘They’re Not Your Husband’

The struggle to find a balance between writing and earning a living is one which most writers have experienced at some time or another. Starving in a garret sounds picturesque until you try it; most writers have a mortgage or rent to pay. But few have written more vividly about the burden and humiliation of work than Raymond Carver.

The struggle to find a balance between writing and earning a living is one which most writers have experienced at some time or another. Starving in a garret sounds picturesque until you try it; most writers have a mortgage or rent to pay. But few have written more vividly about the burden and humiliation of work than Raymond Carver.

He certainly knew the territory. From a poor working class background in Oregon, he married at nineteen, had two children by the time he was twenty, and had to work in a series of dead-end jobs to survive. And boozing was for Carver as serious and time-consuming an occupation as fatherhood and his ‘crap jobs’.

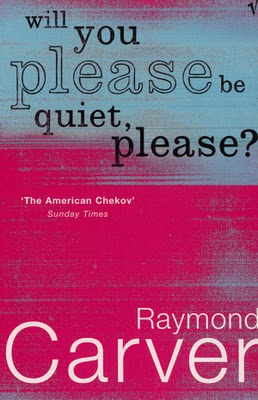

Given the demands on his time and his morale, it’s astonishing that he wrote anything at all. And yet write he did. His first collection of twenty-one stories: Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (McGraw Hill, 1976) was written, ‘by the seat of my pants’ as Carver put it.

‘They’re Not Your Husband’, a terse tragedy of non-communication, is the fourth story in the collection. Whether the gaps in the story are the result of Carver’s artistry or the intervention of his enthusiastic editor, Gordon Lish, the story glows against the white space, and the brief scenes are as bleak and atmospheric as the paintings of Edward Hopper.

The first sentence sets the scene and the story’s central theme: the oppression and humiliation of the ‘crap jobs’ that Carver hated so much:

‘Earl Ober was between jobs as a salesman but Doreen, his wife, had gone to work nights as a waitress at a twenty four hour coffee shop at the edge of town.’

Both Earl and Doreen are trapped, and both are defined by what they do. His role in society is in suspension: he is ‘between jobs’ so his status as ‘salesman’ is suspended too. Doreen is not defined by her waitressing role in the same way: she is defined by the term ‘wife’, and her freedom is restricted accordingly. The coffee shop ‘at the edge of town’ is in a No Man’s Land that recalls the wasteland in the Great Gatsby (and in T.S Eliot’s eponymous poem) as well as those bleak Hopper images of solitary men in bright windows.

Earl is further humiliated when he hears two men talking about Doreen and suggesting she is overweight. Rather than getting angry, or feeling protective towards her, he asserts his authority as ‘husband’, the only social role he has left and insists that she eats less. The account the story gives of her ritual weighing is hard to read: Earl has reduced his wife to a measurable, animal commodity. He has corrupted the intimacy that existed between them, treating her as a sub-standard possession.

Her enforced weight loss exhausts her and threatens her health, but she stoically continues with her work. On a subsequent visit to the coffee shop, Earl encourages another male customer to admire Doreen’s thinner body, but he is uninterested. Earl only succeeds in losing what little dignity he had left.

At the end of the story, just as it appears that Earl can sink no lower, Doreen makes a statement that both reclaims him and traps him in their claustrophobic co-dependency. After Earl makes weirdly lecherous remarks about her appearance, the other waitress in the coffee shop asks: ‘Who is this joker, anyway?’ Doreen replies: ‘He’s a salesman. He’s my husband.’ (The irony here is that he is not a salesman. As the opening line makes clear, he is unemployed. Doreen is actually exaggerating his status. It is left to the reader to decide whether this is an indication of her dogged loyalty or her desperate need to lie to save face.)

The struggle to write became easier for Carver in the end. In 1977 he gave up drink, met the poet Tess Gallagher and moved in with her. In the years that followed, he found literary success and happiness, becoming as he put it ‘beloved on this earth’. In 1987 after a diagnosis of terminal cancer, Carver wrote the poem ‘Gravy’ in which he gave thanks for the extra years of life he had been blessed with.

It’s true that the last phase of Carver’s life were the most productive: during that time he produced three collections of stories and several volumes of poetry, as well as teaching and working as a reviewer. But the earlier, more difficult period of his life was still the primary source of material for his work, and he continued to address the themes of poverty, oppression, soulless work and addiction. To me, this paradox, that he resented work but drew inspiration from it, is inspiring in itself. Writing lives are messy, like first drafts. Inspiration is unpredictable. Too much time can maroon a talent, just as too little can suffocate it.

How has this influenced me? In two ways: firstly because I have too much to do. I have always feared that my writing would be fatally side-lined by all the other demands on my time: being a mother, having a job, studying, running a house. I’m not an alcoholic, but I was never able to take a monastic approach to writing fiction. I like socialising, eating out, going to the cinema, new clothes. And I always felt guilty about this (Why would I not? I feel guilty about everything.) Carver’s struggle to find time to write inspired me and goaded me into action.

And secondly, the famous Carver style. Whether or not he intended his early stories to be so elliptical and whether Gordon Lish was too free with his blue pencil is still a matter of debate. But for me, a story like ‘They’re Not Your Husband’ is close to perfection as it stands. There is a natural synergy between the plain language and the bleak scenes. The gaps and omissions in the dialogue suggest gaps and omissions in the relationships between the characters. The rare descriptive passages stand out against the starkness of the story.

Style and subject matter working together – this is what I found most intriguing. In my own writing, I have developed different registers for different purposes. The cliché about Carver is that his style is pared down to the bone, even though this is less true of his later stories. But what I find most striking is the way that form and subject work together. Reading his stories has helped me develop an ear for dialogue and for the depth of emotion that is hidden in the briefest of exchanges. And it has made me think about ways of describing ‘ordinary’ scenes and ‘ordinary’ people.

All writers have to find a balance between writing and the rest of their lives. Most writers feel that the writing is threatened by their ‘day jobs’ and daily things. Carver made a virtue of this conflict: he made it his subject. Without the grinding, low paid jobs, without the despair and desperation, there would have been no Raymond Carver. There would have been no Earl Ober, no soulless coffee shop. This story would have been impossible to write.

*

Sally O’Reilly is the author of two novels published by Penguin books and a non-fiction guide: How to be a Writer: the definitive guide to getting published and making a living from writing (Piatkus, 2011)

Thanks Sally. Having now had time to read your post (just finished a bathroom remodeling and still cleaning up from it), I can relate to the ‘struggle to find balance in writing’. I always say that if I didn’t have a full-time job how much more time I would have to write but I know how untrue this statement really is. The sad reality is that there are many such days that I waste on nonsense. As much as I would like to say otherwise, having a full-time job has allowed me to be more selective in the free time I do have and sometimes I’m amazed at how much I can accomplish. Of course, life does suffer. How many social invitations have I declined because I’m busy trying to finish my work! I am seeing some fruit of my labor lately and just the fact that I can actually express myself and like what I write, is a gift in of itself. As with anything, being committed to the craft and being disciplined is a must. Without it not much writing will happen.

Wahibe it’s a very brave thing you did to give up a job you hated and write full-time – I’m sure it will pay off. I am sorry to say I really haven’t read much of Raymond Carver and the one story that I did read, underwhelmed me. I am a firm believer that you cannot be forced to like one author over another; either they speak to you or they don’t. As a writer, you do have to explore and study the latest writing styles, etc.,. Once I have time to read more, perhaps I can offer an intelligent comment and appreciate Carver’s style. If he had chosen other subjects to write about, perhaps he wouldn’t have been as successful and famous. Fame and success is so fickle. Sometimes it’s just a question of being at the right place and time. Take Richard Yates who just recently found fame, years after he passed away. Good luck with your own stories and thanks for posting!

Dear Sally thanks for this article, it’s so easy to feel alone juggling time and money, while you’re trying to retain some faith in yourself. It always helps to know others had and continue to have the same struggle. I’ve recently gone through a major shift and chosen to make writing my main occupation. This has been the most important turn in my life, it’s frightening but I wouldn’t go back. Having said that, Raymond Carver was a very astute man in choosing his canvas. The workplace is a fantastic pool of human habit and interaction. In my position, though I hated it profoundly, I was able to read the story of the workplace that no-one else could see, and it has brought me a lot of insight into human behaviour, which finds its way into my writing. My main source however is and will probably always be my family; I have studied us from every turn and continue to watch our stories unfold as individuals and as a family unit. You ended your article by stating that without his early working experience there would have been no Raymond Carver, but I disagree heartily with this. Although his subjects were so insightfully written, Raymond Carver was a brilliant observer of the world inhabited and he was able to portray it in a style and structure all his own, that is the mastery of the writer. There may not have been an Earl Ober, but I promise you there will have been a Raymond Carver. He may have observed and inhabited a different world, but he will have found his way to the pen and paper and put his observations down in his own pared back style, for us to linger over.

Really enjoyed this piece. As a full time father, part-time teacher and ‘struggling’ writer I to find Carver an inspiration. His essay ‘Fires’ is one of the most powerful descriptions I have read of the stresses caused by trying to balance a writing life with a real one.

Great piece, thank you, Sally. I love the idea that too much time can ‘maroon’ talent. I shall comfort myself with this thought rather than moan about life being too busy!