photo by Ariel da Silva Parreira

Discovering Patterned Text vs. Exploring Amplified Context

In his biography of Alice Munro, Robert Thacker quotes New Yorker fiction editor Deborah Treisman on her discovery of the intricacy of Munro’s stories when she came to the magazine in 1997. Reading a Munro story, Treisman says, ‘something from page three will come and hit you on page thirty, but you had not registered the matter when you first read page three.’ This is, of course, an important characteristic of the short story established by Edgar Allan Poe almost two hundred years ago when he defined the word ‘plot’ as ‘pattern’ and ‘design,’ not simply the temporal progression of events. Poe insists that only when the reader has an awareness of the ‘end’ of the work and perceives its overall pattern will seemingly trivial elements become relevant and therefore meaningful.

In ‘The Philosophy of Composition’, his famous essay on how he wrote his poem ‘The Raven’, Poe asserts the importance of considering the work backwards, that is, beginning with its end. Obviously, the possibility of beginning with the end is what distinguishes fiction from reality, what transforms reality into narrative discourse. A narrative, by its very nature, cannot be told until the events that it takes as its subject matter have already occurred. Therefore the ‘end’ of the events, both in terms of their actual termination and in terms of the purpose to which the narrator binds them, is the beginning of the discourse.

It is hardly necessary to say that the only narrative which the reader ever gets is that which is already discourse, already ended as an event, so that there is nothing left for it but to move toward its end in an aesthetic, eventless way, i.e., via tone, metaphor, and all the other purely artificial conventions of fictional discourse. Consequently, it is inevitable that events in the narrative will be motivated or determined by demands of the discourse, demands that do not necessarily have anything to do with psychological or phenomenological motivation of the narrated events in the actual world.

Unfortunately, it is just this attention to pattern and design, this fully integrated sense of interrelated wholeness in which ‘something from page three will come and hit you on page thirty’ that makes good, literary short stories read so infrequently. Not many readers have the time, patience, attention, and dedication to read a story the way an editor such as Treisman reads a story, or as Francine Prose urged in her book Reading Like a Writer a few years ago, the way a writer reads a story.

…a good short story communicates by a delicate and tightly organized pattern of language…

Moreover, the fact that a good short story communicates by a delicate and tightly organized pattern of language – not by argument, direct statement, temporal plot, or moral cliché – means that what the short story strives to communicate is too subtle, too ambiguous, too complex, too inchoate, to be communicated by those rhetorical means by which nonfiction and long fiction often communicate. A good short story cannot be skimmed, read quickly, or adequately summarized. Consequently, when one reads a short story once through, one is often apt to be vaguely dissatisfied or unfulfilled, and therefore less apt to read the next short story he or she encounters – as infrequently as that encounter has become.

Of the two kinds of readers in the world today – those who make a living reading stories and then reviewing them, teaching them, and analyzing them and those who read them for pleasure and engagement – both have found ways of avoiding the frustration of dealing with the story’s linguistically patterned complexity and human mystery and ambiguity. Instead of rereading the story, becoming deeply enmeshed in the sophistication of its linguistic patterned and thematic mystery, readers spring themselves out of the story to seek out its context, i.e. its social influences, political ramifications, biographical revelations, historical frameworks, etc. Unwilling or unable to deal with the story’s linguistic intricacy and thematic ambiguity, the academics do research on these various backgrounds, while the popular readers Google the author and the story for the work’s context, ignoring as much as possible the text of the work.

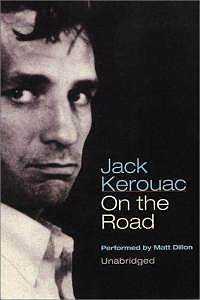

Academic journals that once published engaged encounters with the literary work now publish background context articles that explore historical, political, social, cultural, and biographical frameworks. And for the popular reader, there is Google and now iPad apps. Recently, Penguin published a new iPad app on Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which quickly became a big seller. Although the app indeed features the full text of the iconic book, what has made it so popular is not the text, but the ‘enrichments’ that accompany it – commentary, maps, audio recordings, photos. Editor-in-chief at Penguin, Stephen Morrison, said they decided to bring out On the Road in this format because they were looking for a book with ‘enough resonance,’ by which he means enough supplemental material. Morrison says, ‘We’re at a moment where everyone wants context; we’re constantly Googling this and that.’

background context articles that explore historical, political, social, cultural, and biographical frameworks. And for the popular reader, there is Google and now iPad apps. Recently, Penguin published a new iPad app on Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, which quickly became a big seller. Although the app indeed features the full text of the iconic book, what has made it so popular is not the text, but the ‘enrichments’ that accompany it – commentary, maps, audio recordings, photos. Editor-in-chief at Penguin, Stephen Morrison, said they decided to bring out On the Road in this format because they were looking for a book with ‘enough resonance,’ by which he means enough supplemental material. Morrison says, ‘We’re at a moment where everyone wants context; we’re constantly Googling this and that.’

In early June, after having read recent biographies of Flannery O’Connor, J. D. Salinger, Raymond Carver, and Alice Munro, I posted a blog entry on whether author biographies were helpful for reading short stories. One of my readers, who has her own blog – Reader’s Quest, on which she discusses her experience of one year of reading short stories – commented that her knowledge of the biographical background of stories by the Russian writer Lermontov and Pushkin made the stories remain alive to her, adding to their meaning, noting, ‘I prefer to have some context – the author’s biography and letters (when available), a working knowledge of the culture and period of history in which the author was writing.’

I agree that knowledge of a story’s biographical context (the actual events on which it was based), its publishing context (where and when it was published and for what kind of audience), its historical/cultural context (the social milieu and historical events surrounding its content) are all interesting and worthwhile to the reader. As I watched the demo of the Penguin iPad app for T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland’, with all the video commentary by artists and critics, the dramatization by a wonderful actress, the various readings, including the one by Eliot himself, the annotations of the many esoteric classical and twentieth century references, I was delighted, even tempted to put in my order for one of those expensive iPads myself just so I could use the Wasteland app. And for a poem like ‘The Wasteland’, for which Eliot provided footnotes, these ‘enrichments’ are helpful. For a counterculture classic like On the Road, they are just plain fun. But I am not so convinced yet that background context can help someone understand how and what short stories mean.

I agree that knowledge of a story’s biographical context (the actual events on which it was based), its publishing context (where and when it was published and for what kind of audience), its historical/cultural context (the social milieu and historical events surrounding its content) are all interesting and worthwhile to the reader. As I watched the demo of the Penguin iPad app for T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Wasteland’, with all the video commentary by artists and critics, the dramatization by a wonderful actress, the various readings, including the one by Eliot himself, the annotations of the many esoteric classical and twentieth century references, I was delighted, even tempted to put in my order for one of those expensive iPads myself just so I could use the Wasteland app. And for a poem like ‘The Wasteland’, for which Eliot provided footnotes, these ‘enrichments’ are helpful. For a counterculture classic like On the Road, they are just plain fun. But I am not so convinced yet that background context can help someone understand how and what short stories mean.

Back in 1993, I published a textbook anthology of short stories for D. C. Heath entitled Fiction’s Many Worlds, including a software program entitled HyperStory, which I devised and created to work on both the Macintosh and what was then known as the IBM platform. I spent hundreds of hours programming the software in the Mac HyperCard format and for the IBM in the Toolbook format. Although I did indeed provide as much background information about the stories as I could find, attaching icons to the text on which the students could click to make such information appear, these devices were little more than electronic annotations, providing interesting information, but not really ‘teaching’ the students how to read short stories.

…students learned by practice that reading a story was a process of discovery that took time, attention, and engagement.

The most helpful elements of HyperStory, at least according to my students who used it, were the hidden connections leading students to discover how various elements in the story were related to each other by repetition, thematic similarity, juxtaposition, etc. These interactive icons attempted, as Deborah Treisman said of Alice Munro’s stories, to lead students to discover how something on page three would come and hit you on page thirty. This process slowed the reading down, necessitated rereading, and forced students to discover and respond to the increasing complexity of the story’s linguistic pattern and thematic significance. By reading many stories in the HyperStory format, students learned by practice that reading a story was a process of discovery that took time, attention, and engagement.

I recently posted an entry on my own blog on American writer and teacher Ron Carlson’s examination of his creation of one of his short stories by a process of discovery that took time, attention, and engagement. In my opinion, readers should engage in a similar process of discovery, with no less time, attention, and involvement. I am posting a blog entry later this week that explores Alice Munro’s most recent story in The New Yorker, ‘Gravel,’ to try to shed some light on the kind of attentive engagement necessary for reading a good literary short story.

I think it is easier for ‘new historicist’ academics to unearth historical background material, for cultural critics to generalize about social/political issues, and for all readers to click on icons that pop up contexts than it is to actively and passionately engage in reading a complex short story that explores the ambiguous reality of being an individual human being in a mysterious world. I am all for pursuing the information that contextualizes a short story in its cultural/historical background. I just do not believe that such information should be a substitute for, or a refuge from, the density of the literary work and its complex exploration of mysterious and ambiguous human reality.

I couldn’t agree more, Professor May. It’s so rarely articulated but yes, to my mind too, everything begins with sound, rhythm, tone and hum and charge – almost before any of the sense of the story can emerge on the page. (Coincidentally, I’m writing a piece about this at the moment, in relation to fiction writing in general, so I’m delighted to know of those comments from Amy Hempel and Deborah Eisenberg. Thank you – what serendipity.)

And yes, too: while the contextual detail can interest and even move us profoundly as readers, every writer works at full tilt so that the story and the story alone can ‘speak’ in a way no set of facts can. I love Flannery O’Connor on the stubborn power of a good short story: ‘A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story.’ Famous words now – but a pleasure to repeat here in any case.

Two issues arise for me from this interesting article. One is that of the context. Perhaps it may distract from the story we are reading, towards a speculation about the author’s motivations or state of mind: interesting perhaps, but not really a reaction to the story itself. The other is to do with the complexity issue, which leads me beyond what I can put down in a comment, but is something to do with stories detaching themselves from ‘meaningful reality’, and ending up as ‘meaningless fiction’! (A road not less travelled, it might be argued, by poetry in recent years).

My thanks for Alison MacLeod and Miri Shacham for their kind comments on my article. Alison seems to agree with other fine short story writers like herself that one of the central delights of the short story is its ability to capture the reader with its rhythm, with the form the language creates. American Short story writer Amy Hempel says that when she starts a story, she often knows the beat, the rhythm of the first line or first paragraph, without knowing what the words are. “I’ll be doing the equivalent of humming a tune over and over again,” she says, “and then this tune will be translated into a sentence. I trust that. There’s something visceral about the musical quality of a sentence.” Her fellow short story writer, Deborah Eisenberg agrees, noting, in classic Flaubert fashion, that in her stories, “Sometimes there’s a kind of tonality that I want, almost as if I were writing a piece of music.”

And, yes, Mira, I agree that a knowledge of Raymond Carver’s domestic difficulties with his first wife is an interesting context for the story “Intimacy,” but I think that paying too much attention to the “reality” source of a story (unless it is to appreciate how different the story is from that reality) distracts one from the story. Maryann Carver said, “It takes a story like ‘Intimacy’ to say what the psychologists merely hint at.” I am less interested in what psychologists might say about the relationship between Carver and his wife than I am in how Carver explores the voice of the wife in the story to create a complex human experience. To read a story as if it were a transcription of an actual experience (as Maryann has suggested about some of Carver’s stories) is to trivialize the skill and sensitivity of the artist’s ability to transform mere meaningless reality into meaningful fiction. I don’t think even Kafka would say you have to know his letter to his father to understand his fiction.

I enjoyed reading your article very much but what about a short story like “Intimacy” written by Raymond Carver (from Elephant and others) – the biographical background is esssential for really understanding this story. It is quite obvious that authors use their own biographies as references, can’t the reader be a detective himself ( ” The Purloined Letter”) when he tries to decode the story he is reading? Can a reader refer to himself as a serious reader of Kafka if he hasn’t read Kafka’s letter to his father? Thanks again for writing this delightful article.

Thanks very much for this terrific piece, Professor May. I agree. The passionate engagement of the reader – his or her absorbed attention – is everything. It’s a willingness, isn’t it, to come under the spell of the story; to let its detail, rhythms and form seduce (and re-make) us.

Thanks again. I hope we can meet when you’re next in the UK.