(Relaxing middle aged couple, KeyWest © Bill Frazzetto 2003)

VENUS AND MARS ON A ‘WINTER BREAK’

by JO COLE

Men: Beer, Sex, footie, pub, man flu. That just about sums up the average male member of our species. What about women?

Women: Make-up, hair, friendship, gossip, shoes, multi-tasking.

Spot on? Depends who you ask. Ok, enough of clichés. What about science?

Science demonstrates that the differences between men and women are real. Women have 11% more neurons in the brain’s hearing areas than men so consequently can hear better. Women can verbally express emotions better than men and are less likely to die from accidents. Men are more likely than women to overestimate their abilities. Even male and female retinas are different, with female retinas being thicker.

While all this science may be true, and backed up by numerous studies and statistics, this type of science only offers generalisations about male and female psyches. Science and clichés tell us nothing about the human soul, and the individual human experience. This is where literature shines. Sigmund Freud, king of all psychoanalysts, once said, ‘Everywhere I go I find that a poet has been there before me’. And like poetry, a successful short story offers a porthole into the mind.

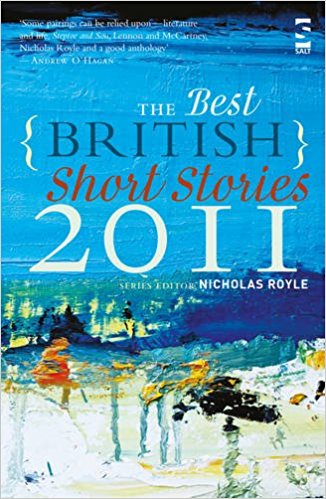

Hilary Mantel’s ‘Winter Break’ portrays the complex undercurrents of a drowning marriage and highlights how a middle-aged couple’s inability to communicate can lead to dangerous consequences. I first read ‘Winter Break’ back in 2011 in The Best British Short Stories 2011. I was a jet-setting newly wed, enjoying the thrill of living abroad, having recently moved to Germany from Angola. Before that, my country of residence had been El Salvador. I was carefree in the way only the young can be. And in love. And newly pregnant.

While researching my first novel, I asked my friends with children the following question: if you could save either your husband or your child from a plane about to crash, who would it be? They answered the child, of course. And yet, despite the new life growing inside me, I said my husband. I couldn’t imagine loving, or feeling closer to anyone more than I did towards my husband at that moment.

While researching my first novel, I asked my friends with children the following question: if you could save either your husband or your child from a plane about to crash, who would it be? They answered the child, of course. And yet, despite the new life growing inside me, I said my husband. I couldn’t imagine loving, or feeling closer to anyone more than I did towards my husband at that moment.

Nevertheless, despite its rather bleak portrayal of a marriage, ‘Winter Break’ spoke to me. I admired Mantel’s story craft, her clever use of ambiguity and her ability to weave a complex tapestry of human emotions.

Despite reading hundreds of short stories since, it is the one I can still remember, and the one whose emotional echo still resonates. It is the short story I wished I’d written, and the one I strive to write.

Seven years on, three children later and back in rainy, cold England, I am more jaded and burdened than I was in 2011. Gone are my newly-wed glasses, and if you ask me about the plane, child and husband again, I’d pick the child. Every time. And if you ask me on an off day, I’d willingly steer the plane and hubby to their fiery demise. Greater understanding of married life, and the struggle, many women face, communicating with husbands has led me to understand ‘Winter Break’ more clearly than before.

Compared with the Limousine of the novel, the short story is a Mini: both get you where you want to go, just in a different style. A novel can span a character’s entire life or can even depict several generations. A short story must be compact, but readers of ‘Winter Break’ don’t feel cheated by its brevity. The emotional connection with its characters is the same as if they’d known them for 200 pages rather than just seven.

Mantel has focused on a single incident in the marriage and has employed what Edgar Allan Poe called ‘the single effect’, a single emotional event that imparts a flash of understanding. In this case it is the couple’s reaction to their driver crashing into an object, assumed to be a goat kid. The story is told linearly and the time scale is brief, just as long as it takes the husband and wife to catch a taxi from the airport to their hotel. Our Venus, the nameless wife narrates the tale. It is set in a nameless country, only hinted at as Greece. The lack of names reinforce the idea that this scenario could happen to any of us, anywhere.

Paragraphs describing the turbulent journey with the grunting, laconic taxi driver are intersected with paragraphs revealing the woman’s lost hopes. So tight is the narration that even the description highlights the distance between the man and wife. For example, the dot on the ‘i’ in their surname on the driver’s placard at the airport is seen by the wife as having drifted away like an island.

The woman yearns for a child, but her husband dismissed her desire long ago. She is unable to move on. Mantel uses allegory in the line, ‘we dress for the weather we want, as if to bully it, even though we’ve seen the forecast’. The wife is not only referring to her flimsy, ill-chosen clothing for a winter holiday, but also to her marriage. Had she entered it hoping Phil, aka Mars, would eventually submit to having children, although she knew in her heart that he probably wouldn’t? Mantel utilises childish language to show the woman’s sorrow. ‘Whoops-a-daisy. There, there. No harm done’, are all things a mother would say to a child after a fall. Unfortunately, for the woman, harm has been done.

Back in 2011, when I was trying for my first child, I visited a male gynecologist who made derogatory remarks about my age, (thirty!) and the number of cysts on my ovaries. He informed me I’d have trouble conceiving. Luckily, he was wrong, but for a time my yearning for a baby engulfed me. It’s not surprising that Mantel manages to capture a childless woman’s preoccupation with babies; Endometriosis stole Mantel’s fertility, and in her late 20s, she underwent an operation that removed her ‘ovaries, womb, bits of bowel.’ Mantel describes a ‘powerful sense’ that she ‘had to draw a line under it.’

The narrator in ‘Winter Break’ hasn’t managed to do this. She says, ‘it was becoming academic now’ rather than it was academic, suggesting that despite her ‘knotted’ genetic strings she believed having a baby was still plausible. The wife believes she understands her husband, and years of marriage have rendered his actions predictable. She knew that Phil would say, ‘I think we made the right decision’, about their holiday choice. She can ‘feel Phil’s opinions banking up behind his teeth’. Yet, as the readers don’t hear Phil’s side, they aren’t privy to his thoughts on his wife, although his actions show little understanding of her.

The right decision he is talking about could easily mean the decision not to have children rather than choice of holiday. For Phil, taking a winter break is a luxury that couldn’t be had if they’d had children. He rejoices in the fact the hotel rates were lower’. For the wife, there is little pleasure in their sunless holiday. Phil treats his wife as a child. He tells the driver that ‘his wife is chilly’, and he ‘rubbed her arms for her, as if to give encouragement.’ He has saved her from pregnancy, childbirth and a life of ‘head lice’, ‘strewn plastic toys,’ and ‘inarticulate demands’ to ‘fix something’. What Phil says is true – he has saved his wife from all these things, only she didn’t want to be saved.

Perhaps readers shouldn’t judge Phil’s lack of understanding of his wife too unfairly. Freud, after all, also once said:

The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is “What does a woman want?”

All I can say to that is: perhaps he should have asked Hilary Mantel.

The troubles between the married couple come to a head when the taxi driver hits something on the road. Phil and his wife feel the impact, but see nothing. Phil declares it to be a ‘kid’, and the reader believes it is a child, until a few lines later the woman thinks of it as ‘tomorrow’s dinner’ and ‘seethed in onion and tomato sauce’. The reader recalls that several goat kids have already leapt across the car’s path.

Mantel’s skill is evident in her ability to do what all new writers tire of hearing about in their newly critiqued pieces: show not tell. But rather than a lengthy ‘show’, Mantel represents the killing of the kid in three words: ‘thud, thud, thud’.

Did you hear it? I did.

The wife is unable to communicate with her husband. They ‘did not look at each other’, and ‘she understood that, they wouldn’t, either of them mention this dire start to their winter break’. Phil tries to take her hand, but she ‘twitched it away’. The woman is left to interpret the scene without input from the others and convinces herself, and the reader for that matter, that what the driver did was humane and necessary to put a suffering animal out of its misery. This whole passage is a clever piece of subterfuge and the wife proves to be an unreliable narrator.

Arriving at the Royal Athena Sun, Phil and the wife jump to retrieve their bags from the boot before the porter discovers the kid next to their luggage. By not saying anything, they are, as the wife admits, complicit in the driver’s actions, although the wife still believes the driver did nothing wrong. She is shocked when the tarpaulin covering the kid is inadvertently pushed aside to reveal ‘not a cloven hoof, but the grubby hand of a human child’.

This staggering last line leaves the reader reeling with questions, but the main questions are: Did Phil know it was a child? Was this why he remained silent? Is he prepared to let the taxi driver get away with murder? And most importantly, did the wife really know her husband at all?

It is rather strange that Phil used the word ‘kid’ after the crash. You’d think the non-specific word, goat, would spring to mind more easily. The reader is left to fill in the blanks and ponder what the wife does next. Losing a child is often likened to losing one’s hand, and it is powerful that Mantel chose this body part to highlight. There is symmetry in the story with the death of the unknown child echoing the woman’s lost youth and fertility. But the fact, she did nothing, and said nothing would make the reader wonder whether she was suitable for parenthood, after all. Phil certainly wouldn’t be ‘suited’ to fatherhood, as the woman believes.

Great short stories waste not a single word, and this certainly is the case with ‘Winter Break’. What the reader is left with at the end of the story is a warning. We again see the irony in the woman’s words: ‘whoops-a-daisy. There, there. No harm done’. Harm will be done if communication between a husband and wife breaks down to such an extent that they are unable to act and unable to speak out. Would the child have lived if they’d questioned the taxi driver and stopped that awful ‘thud, thud, thud’?

Perhaps one thing Mantel and Freud can agree on is the importance of talking. Right, where’s my hubby? It’s time for date night, and a good old chat.

~

JO COLE writes when a gap in the chaos of raising three kids creates emerges. Jo has an MA in Creative Writing, and her debut novel was long-listed in Mslexia’s novel competition. She likes to have many projects on the go; currently, she is working on a dystopian novel and a children’s novel. She writes short stories for women’s magazines.