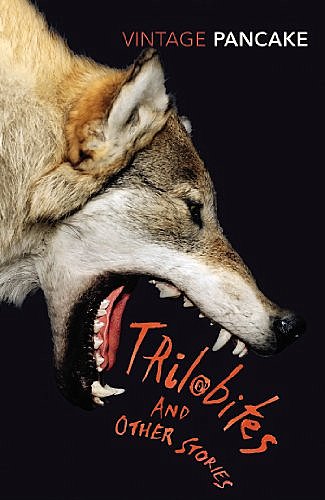

(Untitled © Burlan Marius, 2012)

MOONS BLACKENED WITH COAL DUST:

BREECE D’J PANCAKE’S ‘TRILOBITES AND OTHER STORIES’

by ALISON ARMSTRONG

~

The truth will set you free. But not until it is finished with you.

– David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest

~

I came across a copy of Breece D’J Pancake‘s collection Trilobites and Other Stories in a car boot sale. Fittingly enough, it was among tools: picks, shovels and spades. A find, waiting to be unearthed like so many objects in the stories. I wrestled with it for the next few days, feeling physically drained and excited by the visceral urgency of the language, the sheer bleakness of the stories.

The hard-hitting stories are set in rural West Virginia, where the characters labour to survive in a blighted landscape of failing farms, industrialised remnants of mines and nature struggling to reassert itself. They are defined by the futility of this struggle, tormented by impossible aspirations and the ever-present desire for escape.

Tim Heffernan, writing for the The Atlantic in April 2004, says of Pancake, ‘he wrote exclusively about the sons and daughters of the dissipated Appalachian world in which he was raised. They were the people he knew, and he seems to have felt honour-bound to give them a voice.’

The author’s language is idiomatic, heavy in dialect – turkles rather than turtles, Injuns instead of Indians, and ‘champion’ is rendered champeen. It adds an intricate local depth, a richness of texture to the reading of the stories.

All of the stories happen over hours or days, yet they are framed by ancient and glacial time, symbolised by the constant presence of arrowheads and fossils. The landscape has been worked on, even the mountains themselves; they govern the present and remind us that history is extant. Pancake’s characters are dwarfed by this past. Tim Heffernan writes that the ‘touchstones’ of Pancake’s failed south are ‘things much older: the land itself, with its isolating hollows and impoverished soil; the Indians who built immense burial mounds in honour of their dead; and the even more ancient seas from which the hills rose.’

All of the stories happen over hours or days, yet they are framed by ancient and glacial time, symbolised by the constant presence of arrowheads and fossils. The landscape has been worked on, even the mountains themselves; they govern the present and remind us that history is extant. Pancake’s characters are dwarfed by this past. Tim Heffernan writes that the ‘touchstones’ of Pancake’s failed south are ‘things much older: the land itself, with its isolating hollows and impoverished soil; the Indians who built immense burial mounds in honour of their dead; and the even more ancient seas from which the hills rose.’

In ‘The Mark,’ ancient rites hold sway. Reva’s possible pregnancy is tested by injecting her blood into a rabbit and then cutting it open to read the swelling. ‘They were going to kill the rabbit and look for her secret in its organs….[but] they would find no confessions in the rabbit’s ovaries.’ Towards the end of the story we are told that Reva was sorry the rabbit had died for nothing.

Pancake’s characters seem caught at a crossroads between past and future. Often they are wrestling with the past in order to understand the present, to find redemption. Yet redemption always eludes them. This is most apparent in the story ‘In the Dry’ which begins with Ottie’s return ‘home’. Gerlock, Ottie’s foster father suspects he is responsible for the injury that has left his real son, Bus, paralysed, and he wants to know what happened on the bridge. He keeps asking Ottie, even as others hold him back, what happened. But Ottie does not seem to remember. As in many of Pancake’s stories, there is a dark and pointless violence lurking here. Before Bus kills Ottie’s dog Bus says ‘I’m going to show you something, Ottie.’ It is an assertion that is repeated throughout the story, and seems to be linked to the accident on the bridge, for before that, too, Bus says his line: ‘Show you.’ The paragraph ends with a description of the hills where Ottie ‘waited out the night’ with the carcass of his dead dog. There is the overwhelming feeling throughout the stories that the real meaning is deeply buried beneath layers of history, and that no amount of excavating will ever bring it to light. Nevertheless they are bent constantly towards it, but the past will not leave them alone until it has chewed them up, spit them out.

Many of the stories are perfect constructions, concealing as much as they reveal. We delve into the layers, as the stories move and shift through suggestions of what is going on, what is coming to light. Always we are left wondering. As are the characters.

In ‘Trilobites’, after the death of his father, Colly is left stumbling around for meaning; everything he knows has collapsed around him. In ‘In the Dry’, Ottie’s return seems to seek atonement. Coming back after all those years, though, he can offer only pain as he fails to help old Gerlock: he cannot remember the accident; he cannot even draw any meaning for himself. In ‘Hollow’, Bud, abandoned by his lover, rouses himself from the pain of ‘trailer heat’ to go hunting one last time. He plans a strike against the mine that has destroyed his lungs. This bid for freedom might have held some cathartic power, but it comes too late and we cannot believe in it. In ‘The Mark’, Reva is trapped by her own unnatural longings for her brother, Clinton, who has left this place of their long dead parents, and for whose return she waits. She is in a state of limbo, listless and unable to commit to any desires for the future. Indeed, the future itself seems impossible. She is not pregnant. There is a suggestion that she cannot become pregnant because of her unnatural desires. In a sideshow tent, Carlene warns her as she watches spider monkeys rutting a female: ‘I knowed a woman mark her baby thataway….. [B]aby was born lookin’ just like a monkey.’

Minds are perpetually troubled by the past. Finding no solace in each other, or in anything they can bring from the past, objects take on a talismanic significance. They become symbolic, taking on weights of meaning, at once intimating and holding back secrets. Objects are constantly being unearthed and collected: fossils; coal; bones and skulls and arrowheads from Indian burial grounds; a perfect mouse skeleton, found in the hollow of a tree, which turns to dust as Ottie touches it. Photos fade and look back, unknowing, at the false son. In ‘The Mark’:

[Reva] stared at the sycamores and water maples along the riverbank. Secret totems hung there as gifts to the ghost trees of her parents: a necklace from Reva, a charmed dog-bone from Clinton, bits of glass on fishing line to make the trees glitter in the winter sun.

In ‘In the Dry’, Ottie has made a childhood habit of collecting stuff. When he returns it is still there:

As he tries to find the first thing to turn them all this way, the pieces of broken life fall into his mind, and they fall without the days and nights to mend them…Those things are still there: dried insects, Sheila’s mussel shells from Two-Mile Creek’s shoals, arrowheads, a plaster angel. All things he saved.

When Sheila asks whether he still collects things now ‘His smile falls away. “No, I quit saving stuff.”’

Their homes are all they know, and though they want something more, it is always beyond their grasp. They are cursed with a desire to leave but have no real plans for doing so. Even though ‘Trilobites’ ends with Cally intending to leave, you feel certain that he will never achieve his goal. The story is one of frustrated desires – which are so choked by the poisonous air that Cally cannot even recognise them for what they are. Like his desire for Ginny, which he abandons before it can offer salvation, and before it can be thwarted.

In ‘Trilobites’, Cally’s father ‘is a khaki cloud in the canebrakes, and Ginny is no more…than the bitter smell in the blackberry briers up on the ridge’. People become the landscape that ensnares him. In ‘Fox Hunters’, ‘insecurity crawfished through his blood’ – verb and animal have mutated into each other.

Throughout the collection, characters struggle in spiritual isolation. They suffer, and are in a continual state of frustrated need. Pancake’s characters may seek escape in each other, but none can find it. Nobody ever gets what they need, what they want. One of the few relationships that seems to provide some kind of comfort is found in ‘Fox Hunters’. It is characteristic of the harsh loneliness of Pancake’s world that, for Bo, that relationship should be with a waitress, a provider of sustenance/comfort to all transient passers-by. In other stories, human relationships are a burden. In the final story, ‘First Day of Winter’, a blind old man cries when his son tells him he is not wanted by his favoured other son. It is pitiful, ending with ‘the soft rasp of [the] father’s crying breath.’ In ‘In the Dry’, Sheila tells Ottie ‘I aint never been loved.’

Kurt Vonnegut called Breece D’J Pancake ‘the best writer, the most sincere writer I’ve ever read.’ The quote is from the blurb of the Vintage edition, and comes from a letter Vonnegut wrote to Pancake’s mentor, John Casey, after the news of the younger writer’s suicide. Pancake shot himself in the head in 1979, aged 26.

Kurt Vonnegut called Breece D’J Pancake ‘the best writer, the most sincere writer I’ve ever read.’ The quote is from the blurb of the Vintage edition, and comes from a letter Vonnegut wrote to Pancake’s mentor, John Casey, after the news of the younger writer’s suicide. Pancake shot himself in the head in 1979, aged 26.

Pancake’s characters endure hardships; suffer tragic deaths. Bo’s dad is described as having ‘sucked so much mine gas, they had to bury him closed coffin because he was blue as jeans.’ They die in wreckages; they are crushed in mines; metal is lodged in brains; coal dust chokes lungs; wrists are cut ‘down to the leaders.’ The stories lie on the margins, exploring the lows of the human condition – alcoholism, incest, murder, war, adultery, rural poverty. They are littered with dying farms, murdered dogs, cock fights, disease, suicide, underage prostitution, and dead fathers. And it is there, on the edges, where our humanity is questioned most, where it teeters and fails. What is it that makes us human? That makes us endure? These are the questions Pancake seems to ask, over and over again.

Often in these stories, there is violence, incidental or climactic. In ‘Hollow’, violence comes to release frustrations, yet there is no deliverance. At the end of the story, when Buddy is gutting a deer he has shot, ‘something inside the carcass jolted, moved against the knife point’. It is the deer’s unborn fawn, a symbol not of new life but of futility. There is no redemption, here, only a claustrophobic sense of bad things looming, and as the story moves towards its end, the pursuer becomes the pursued:

in the bush by the trail, a bobcat crouched, waiting for the man to clump by, its muscles tight in the snow and mist. Claws unsheathed, it moved only slightly with the sounds of his steps until he was far up the trail, out of sight and hearing. The cat moved down the trail, stopping only to sniff at the blood-spit the man left behind.

The story ends with a description of this bobcat ‘on a knoll in the ridge, run there by the dogs, the bobcat watched, waiting for the man to leave’. There is something prophetic in this, nature harried and hunted, biding its time.

Indeed, if there is any kind of redemption to be had it is in this idea of nature biding its time; however degraded and impoverished they are, those great hills will always be there. But there is no human redemption here, no catharsis, no human healing. Human beings do not hold sway. They have no control. The last line of ‘Trilobites’ is perhaps one of the most hopeful lines in the whole collection: ‘I walk, but I’m not scared. I feel my fear moving away in rings through time for a million years.’ It is only humanity’s dwarfing by millions of years of history and pre-history that provides an escape, a line of flight. It is only, in a sense, in the annihilation of the human, and of what it means to be human, that the stories deliver any kind of ending.

Pancake’s writing is raw. It is stripped of artifice, of sentimentality, even of warmth. His writer’s gaze is unrelenting in what it finds, what is wrought from it, what is concealed.

~

ALISON ARMSTRONG has been writing short fiction for many years and has been long listed and short listed for several prizes and awards. Last year she won a Northern Writers’ Award for fiction and was commended in the Bath Flash Fiction Award. She lives and works as a teacher, cleaner and painter in Lancaster.

ALISON ARMSTRONG has been writing short fiction for many years and has been long listed and short listed for several prizes and awards. Last year she won a Northern Writers’ Award for fiction and was commended in the Bath Flash Fiction Award. She lives and works as a teacher, cleaner and painter in Lancaster.