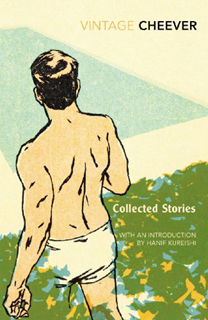

('Swimmer'© bswise, 2015)

THE COLLAPSE OF POST-WAR MASCULINITY IN “THE SWIMMER”

By CHRIS MACHELL

Frank Perry‘s 1968 film The Swimmer has been somewhat forgotten among the milieu of 1960s American independent cinema. Like the meeting point between the youthful counter-culture of The Graduate and the mid-life crisis of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, The Swimmer is arguably just as important in its study of the collapse of conventional American masculinity. Perry’s film is a faithful adaptation of John Cheever‘s short story of the same name, which first appeared in a July 1964 issue of The New Yorker. The Swimmer tells the story of wealthy suburbanite Ned Merrill who decides, on a whim, to swim through his neighbour’s swimming pools to get home, dubbing his journey ‘The Lucinda River’ after his wife.

Ned begins his journey with self-regarding vigour, surveying the valley that houses his neighbours as if it were his own personal kingdom. But over the course of the afternoon, his vigour gradually wanes and his neighbours become increasingly frosty towards him. Cheever’s story is celebrated for its surreal qualities – the span of a year is truncated into just a single afternoon, and Ned’s lapses in memory, forgetting that his wife and children have apparently left him, create an unreliable sense of reality.

The story opens with a depiction of Merrill’s supreme self confidence:

Neddy Merrill […] was a slender man—he seemed to have the especial slenderness of youth […] he had slid down his banister that morning and given the bronze backside of Aphrodite on the hall table a smack […] while he lacked a tennis racket or a sail bag the impression was definitely one of youth, sport, and clement weather. He had been swimming and now he was breathing deeply, stertorously as if he could gulp into his lungs the components of that moment, the heat of the sun, the intenseness of his pleasure. It all seemed to flow into his chest.

Here is a man utterly at ease with himself, breathing in and embodying the fecundity of life in full bloom. Yet even here, there are cracks in Merrill’s statuesque persona. Though he gives the ‘impression’ of youth, the narrator notes that Merrill “was far from young”, and indeed he may well have been “compared to a summer’s day, but one in its “last hours”. The symbolic end of Merrill’s summer is later suggested when he notices leaves on a maple tree turning brown. Although he tells himself it must be because the tree is ‘blighted’, he can’t escape the ‘peculiar sadness at this sign of Autumn’.

Here is a man utterly at ease with himself, breathing in and embodying the fecundity of life in full bloom. Yet even here, there are cracks in Merrill’s statuesque persona. Though he gives the ‘impression’ of youth, the narrator notes that Merrill “was far from young”, and indeed he may well have been “compared to a summer’s day, but one in its “last hours”. The symbolic end of Merrill’s summer is later suggested when he notices leaves on a maple tree turning brown. Although he tells himself it must be because the tree is ‘blighted’, he can’t escape the ‘peculiar sadness at this sign of Autumn’.

In the film, we don’t see the attempts at boyish banister-sliding, yet his quoting of the Biblical Song of Solomon – “how beautiful are thy feet in sandals”, and his clumsy, self-conscious flirting with Helen Westerhazy betrays a juvenile self-regard of his own (questionable) intellectual and sexual prowess. Merrill’s insistence on reminiscing about old college japes is juxtaposed with the plane his friends have to catch; their pressing schedule not only suggests the urgency of time’s passing but also serves as a metaphor for Merrill being stuck in an extended adolescence, left behind by his peers.

The limitations of Merrill’s ambitions, too, become increasingly apparent. Styling himself as “a pilgrim, an explorer, a man with a destiny”, he deludes himself that his journey is an epic river voyage instead of just a trudge home through the suburbs. Cheever underscores the smallness of Merrill’s horizons with the chattering gossip of Merrill’s neighbours, who do little more than crowing that they ‘drank too much last night’. Yet Merrill’s patronising characterisation of them is arguably even more pitiable: “He saw then, like any explorer, that the hospitable customs and traditions of the natives would have to be handled with diplomacy if he was ever going to reach his destination”.

The surreal qualities of the story are retained in the film adaptation, with cinematographer David L. Quaid using the reflected light of the water to create a soft psychedelia that frays at the edges of reality. Jarring cuts and out of place close-ups may be a result of awkward editing, but equally they create the sense of a fractured identity – an unreliable narrator whose sense of continuity and perspective are gradually unravelling. Indeed, Merrill’s reality is centred entirely around his own self image; the integrity of one necessarily depending upon the other. Merrill sets himself against the staid suburban lifestyles of his neighbours, yet he is inextricably part of that world, like a boy pretending to be an outlaw before his mother calls him in for dinner. The irony is that, though ostensibly in opposition, the materialist individualism of his neighbours and the counter-culturalism that he fancies himself part of are just different expressions of a post-war American masculinity in crisis.

Where Cheever employs increasingly surreal prose, moving from a warm summer’s day to an autumnal evening to depict this discursive breakdown, the film invents new incidents and rearranges elements of the story’s structure to highlight Merrill’s crisis. For example, Perry adds a lengthy episode where Merrill leers over his daughters’ old babysitter, Julie Hooper (Janet Landgard). This sequence arguably forms the thematic crux of the film, explicitly juxtaposing Merrill’s generous self-perception against objective reality. As he preposterously shows off by leaping over showjumping hurdles, the slow motion footage has two meanings. Reflecting Merrill’s own sense of his stallion-like magnificence, his ludicrous antics, slowed down to allow us to pick apart and laughed at them, betray him as a pitiful, lecherous fool.

Where Cheever employs increasingly surreal prose, moving from a warm summer’s day to an autumnal evening to depict this discursive breakdown, the film invents new incidents and rearranges elements of the story’s structure to highlight Merrill’s crisis. For example, Perry adds a lengthy episode where Merrill leers over his daughters’ old babysitter, Julie Hooper (Janet Landgard). This sequence arguably forms the thematic crux of the film, explicitly juxtaposing Merrill’s generous self-perception against objective reality. As he preposterously shows off by leaping over showjumping hurdles, the slow motion footage has two meanings. Reflecting Merrill’s own sense of his stallion-like magnificence, his ludicrous antics, slowed down to allow us to pick apart and laughed at them, betray him as a pitiful, lecherous fool.

Following this scene in the film, the busy highway that Merrill crosses and the public pool he is subsequently forced to endure in the story is moved to the end of the film to better punctuate the collapse of Merrill’s fantasy. His humiliation at the pool naturally follows his frightening off of Julie, which then leads into the encounter with his former mistress, Shirley Adams. The film prolongs this sequence to elaborate both on the tawdry nature of their affair, her bitter feelings towards Merrill and his own persistent self-delusion, insisting that she loves his unwelcome caresses even as she tells him to stop.

The final collapse in both the film and book comes when Merrill arrives home to find his house derelict and empty, clearly vacant for months. The breakdown of Merrill’s heroic self-image serves as a critique of mid-twentieth century American individualism, further underscored by the casting of conventionally masculine but ageing Hollywood star Burt Lancaster in the title role. The Swimmer is as much as an attack on the self-involved counter-culturalism of Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation as it is on self-satisfied wealthy suburbia. The decadent materialism of Merrill’s classically-liberal wealthy peers and Merrill’s own cod-Romantic self satisfaction are merely banks on opposite sides of the same narcissistic river. In this, The Swimmer critiques the root discourse that motivates both Merrill and his chattering neighbours. An invention of his hyper-masculine imagination, the Lucinda River sweeps Merrill along in a desperate tide of self delusion and narcissism. Yet the current can only sustain him for so long, and as summer symbolically ends and the heavens above him open, the banks of his fragile illusion are washed away.

~

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack. His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack. His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.