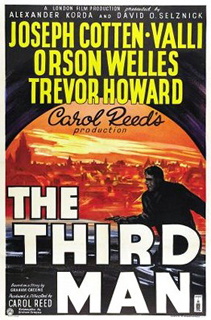

(‘The Third Man’ © Christian Mayrhofer, 2010)

THE FRACTURED CITY IN THE THIRD MAN

by CHRIS MACHELL

A fortuitous mixture of beautiful cinematography, flawless screenplay, and, in Orson Wells, one of the screen’s greatest actors at the top of his game, The Third Man defines the term ‘lightning in a bottle’. Topped off by Anton Karas’ iconic zither music, Carol Reed‘s noirish direction perfectly complements the post-war European setting of Graham Greene‘s screenplay. By 1949, many of Greene’s novels and short stories had already been adapted into film, including ‘A Gun For Sale’ as This Gun for Hire, starring Alan Ladd, ‘The Basement Room’ as The Fallen Idol, and perhaps best of all, the 1947 gangster thriller Brighton Rock.

The Third Man shares many of these films’ preoccupations with crime, morality and urban decay and it is arguably the most artistically successful Greene adaptation. It is also the most fundamentally cinematic, right down to its roots as a short story. In his preface, Greene explains that after Carol Reed approached him to write a screenplay for a film set in post-war Vienna, Greene wrote his short story essentially as an exercise to figure out the story:

To me it is almost impossible to write a film play without first writing a story. Even a film depends on more than plot, on a certain measure of characterization, on mood and atmosphere; and these seem to me almost impossible to capture for the first time in the dull shorthand of a script.

Moreover, Greene suggests that it is the film, not the short story, that is the most complete version:

‘The Third Man’, therefore, though never intended for publication, had to start as a story before those apparently interminable transformations from one treament to another […] To the novelist, of course […] he cannot help resenting many of the changes necessary for turning [their work] into a film; but ‘The Third Man’ was never inteded to be more than the raw material for a picture […] The film in fact, is better than the story because it is in this case the finished state of the story.

It’s certainly rare for authors to capitulate to the changes made to their adaptations, much less admit that those changes improved on the original work. Nevertheless, it’s fascinating to think of the short story as a first draft, and complicates the relationship between adaptation and original.

The vast majority of readers of ‘The Third Man’ will be approaching it already having seen the film. Accordingly, it’s almost impossible not to imagine Karas’ zither theme as the tune Harry whistles throughout the story (a quality to which Greene himself subsequently alluded), or even to imagine the four quarters of Vienna’s smashed city streets in the chiascuro of Robert Krasker’s beautiful cinematography. And is there a better example of perfect casting than Orson Wells as the effortlessly charismatic ne’er do well Harry Lime? Calloway’s description of the character could easily be a description of the actor himself:

The vast majority of readers of ‘The Third Man’ will be approaching it already having seen the film. Accordingly, it’s almost impossible not to imagine Karas’ zither theme as the tune Harry whistles throughout the story (a quality to which Greene himself subsequently alluded), or even to imagine the four quarters of Vienna’s smashed city streets in the chiascuro of Robert Krasker’s beautiful cinematography. And is there a better example of perfect casting than Orson Wells as the effortlessly charismatic ne’er do well Harry Lime? Calloway’s description of the character could easily be a description of the actor himself:

“Don’t picture Harry Lime as a smooth scoundrel. He wasn’t that. The picure I have of him on my files is an excellent one: he is caught by a street photographer with his stocky legs apart, big shoulders, a litttle hunched, a belly that has known too much good food for too long, on his face a look of cheerful rascality, a geniality, a recognition that his happiness will make the world’s day.”

We don’t know if Greene already had Wells in mind for the role, but if he didn’t it is a remarkably prescient physical description.

At just shy of 100 pages, the short story is almost entirely recreated on screen, though invariably certain elements are left on the cutting room floor. As with the story, the film is still told from Colonel Calloway’s perspective, but is somewhat downplayed with only really the opening voice-over narration emphasising that Calloway is relating the story second-hand. Another corrupt Colonel, working for Lime in the story, is excised completely from the film, as is a brief episode where Lime’s girlfriend Anna is arrested by the Russian military police. Little narrative or thematic cohesion is lost in these cuts, however, and they serve to streamline the already economical plot.

Other, subtler changes alter the film in more interesting ways. Rollo Martins’ first name is changed to Holly to reflect his nationality changing from British to American, a practical issue of casting but one which reflects a more fundamental change in character. Rollo Martins is a much darker, more ambivalent character than his American screen counterpart. Calloway’s more prominent narration comes into play here, describing Martins as a dual-personality – the volatile Rollo and the ‘steady, careful’ Martins, like a post-war Jekyll and Hyde. In this, Martins mirrors Harry Lime, projecting one version of himself while hiding his meaner, more cynical aspects in the shadows. The sense of cynicism plays out differently in the story and film – Martins is far more likeable in the film, yet his sentimental refusal to believe Calloway’s account of Lime arguably makes Rollo more sympahtetic than his counterpart, Holly. Moreover, the film has Calloway tell us that the black market “does tempt amateurs, but, well, they can’t stay the course like a professional”, punctuated with a casual shot of a body floating in the Danube – presumably one of the amateurs to which Calloway is referring.

Nevertheless, the Vienna of the story is a more fractured place than in the film, with the divisions between the American, English, French and Russian quarters much more stark in the story. Where the Western Quarters are relatively benevolent, the Russian Quarter is more visibly scarred by the war. And offering a hideout for Lime after he fakes his death, it is a fundamentally more malignant space. Though Lime also hides in the Russian Quarter in the film, it is not any more noticeably wrecked than the other areas of the city, nor is it as diplomtically difficult to access as it is in the story. Indeed, where it could be said that the story’s city is divided horizontally, carved up by the occupying forces, the film’s visuals emphasise the city’s verticality. While the likes of Calloway work to maintain a modicum of respectability above, the corrupt network of the sewers below – used by Lime to run his rackets – constantly threatens to throw the city into disorder.

Nevertheless, the Vienna of the story is a more fractured place than in the film, with the divisions between the American, English, French and Russian quarters much more stark in the story. Where the Western Quarters are relatively benevolent, the Russian Quarter is more visibly scarred by the war. And offering a hideout for Lime after he fakes his death, it is a fundamentally more malignant space. Though Lime also hides in the Russian Quarter in the film, it is not any more noticeably wrecked than the other areas of the city, nor is it as diplomtically difficult to access as it is in the story. Indeed, where it could be said that the story’s city is divided horizontally, carved up by the occupying forces, the film’s visuals emphasise the city’s verticality. While the likes of Calloway work to maintain a modicum of respectability above, the corrupt network of the sewers below – used by Lime to run his rackets – constantly threatens to throw the city into disorder.

The story’s sense of a fractured city is translated in the depiction of Harry Lime himself. A charming rascal guilty of terrible crimes, it is impossible not to grin with delight when, in the film’s most famous shot, the light from a window illuminates Wells’s face, eyes knowingly twinkling, irreverant smile creeping across his boyish cheeks. Wells’ performance is crucial in the camera’s infatuation with Lime, and in this sense, the film’s relationship with the character is far more ambivalent than the story’s ultimate condemnation of him.

Nowhere is this clearer than in his death – where the story’s Lime whines and squeals pitifully, the film’s Lime nobly accepts his fate, simply nodding to Martins to pull the trigger of his gun. The difference in endings too is important: in the story Anna walks from Lime’s funeral arm in arm with Martins, whereas in the film she walks away from him in silence, unable to forgive Martins’ betrayal of his friend.

Lime is an amoral monster who sold penicillin cut with sand to sick children, then faked his own death – killing two people into the bargain – to escape the consequences. In the story, Martins is infatuated with Lime, and Wells’ performance invites us to perceive him through Martins’ starry eyes. We favour the rascally charm while conveniently ignoring the hidden, seething darkness flowing like the sewage in Vienna’s underground tunnels.

~

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

Dr. Chris Machell lives in Brighton with his partner and works at the University of Chichester. He is also a freelance film critic, reviewing films for the award-winning website CineVue, and has also written for Little White Lies, The Quietus, The Skinny and the BFI. He occasionally writes about video games, and recently appeared as a guest on the video game music podcast, Forever Sound Version. You can find all of Chris’ archived work to date on his blog, CultCrack.

His favourite film is Bride of Frankenstein, and his favourite video game is the cult Sega classic, Shenmue.

One thought on “The Fractured City in The Third Man”

Comments are closed.