('Look' © Gonzale, 2006)

*

TAKING SIDES

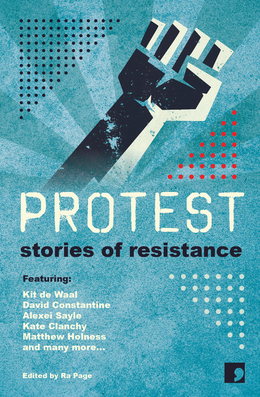

PROTEST: STORIES OF RESISTANCE

by NICOLE MANSOUR

*

The view from the walkway that first Monday morning in September was uncanny. Gloucester Road – one of Hong Kong’s busiest motorways – was deserted. No buses, or taxis, or ostentatious pink Mercedes. Camping tents and yellow umbrellas, bright and open under a steaming, hazy sun, had replaced the traffic. The road was chalked with messages of freedom and equality; road signage had been unofficially edited: this lane for democracy.

I walked the length of it, from Jardine House – otherwise known as ‘the building of a thousand arseholes’ – to Causeway Bay and back again, undisturbed by vehicles, or any sort of anarchy. Instead, I was offered free bottles of water and yellow ribbons to pin to my shirt. For Hong Kong’s ‘Occupy Central’ demonstration, or ‘Umbrella Movement’ as it soon came to be known – Hong Kong residents’ entreaty to the city’s increasingly pro-Beijing government for universal suffrage – was, if nothing else, the epitome of a peaceful protest. And it was this element of the protest – its calm, honest appeal – that so strongly incited both my empathy (for its protestors) and my rage (against the government). My visits to Gloucester Road during its seventy-nine-day occupancy in the autumn of 2014 are the closest I’ve ever come to actively protesting a cause.

As I read Ra Page’s introduction to the Comma Press anthology Protest: Stories of Resistance, I was reminded of my experience in Hong Kong three years ago, an experience I feel strangely and sadly privileged to have witnessed first-hand. I also became intensely aware of the currents often connecting campaigns, which as Page notes, ‘…form a continuum: one where ideas, tactics and philosophies can be seen flowing between movements, triggering new conversations, inspiring and shaping new methods’.

In the twenty short stories that follow, the history of British protest is revealed through well-researched and historically accurate fiction, and this continuum, this flow between movements, is strikingly uncovered.

Arranged chronologically, the collection begins with Sara Maitland’s account of the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381 and goes on to relate protests dating from the early 1600s, to the Radical War of 1820, Chartism, anti-Vietnam War  protests, the Night Cleaner’s Strike of the 1970s and the New Cross Fire and Brixton Riots, all the way through to the anti-Iraq War demonstration of 2003, by writers including Kit de Waal, David Constantine, Alexei Sayle, Kate Clanchy and Matthew Holness, among others.

protests, the Night Cleaner’s Strike of the 1970s and the New Cross Fire and Brixton Riots, all the way through to the anti-Iraq War demonstration of 2003, by writers including Kit de Waal, David Constantine, Alexei Sayle, Kate Clanchy and Matthew Holness, among others.

There are also stories that have been largely neglected by historians, such as that by Sandra Alland describing the Blind Man’s March of 1920, a campaign that would eventually result in the Blind Persons Act 1920, and which has since become the basis for other acts legislated for disabled people.

Each story is accompanied by an afterword by a historian, sociologist or eyewitness, emphasising the street-level perspective of the fiction preceding it. Indeed, some of the first-hand accounts – such as Lyn Barlow’s memories of her experiences at Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp and Avtar Singh Jouhl’s chronicle of Malcolm X’s visit to racially tense Smethwick in 1965 – feel unpleasantly related to demonstrations taking place today.

I was especially moved by Michelle Green’s story of the Suffragette movement, ‘There Are Five Ways Out of This Room’. One of the briefer and most immediate pieces in the collection, it is piercingly narrated by an unnamed woman. Imprisoned and forcibly fed while engaged in a hunger strike, to ensure she serves her full gaol term, the woman considers the few and impossible ways of escape from her cell:

One: crack in the corner, where the wall meets the floor, where the sun performs a quick seven minute sweep early each morning before disappearing across the prison walls for another day and night. It’s wide as a pin, that crack, maybe two pins side by side, but big enough for the small army of fork-tailed silverfish that emerge when it’s quite enough and still, surveying the floor and eating what I don’t.

The immediacy and closeness of Green’s first person narrative evokes the horrendous claustrophobia of imprisonment and the vehemence of persecution. Thus, it effectively elucidates just what the suffragettes endured for the right to vote – for our right, as women, to vote. For that freedom was not simply granted by higher powers but demanded: it was a hard-fought battle that necessitated courage in the face of cruel adversity and a willingness to become an outcast. Indeed, Green’s portrayal of the suffragette brought to mind something a dear friend of my parents’ once elucidated to me: that as a woman, I should always vote, for barely more than one hundred years ago, other women died earning me that right. And I remember that thoughtful counsel every time I step inside a polling booth, no matter how insignificant I believe my vote may be.

What, perhaps unsurprisingly, links each of the stories here are the reasons the protests occurred in the first place: economic divisions, unwanted military escalation, the threat of new technologies, the further marginalisation of an already marginalised section of society and ever-intensifying government absurdity. And these reasons seem even more relevant today as they may have years, decades or centuries ago.

More than this, Protest: Stories of Resistance, with its well-researched and historically accurate fictions, proves an informative and effectual challenge to mainstream media and the increasingly allegorical ‘fictions’ we find in journalism worldwide.

As one comes to the end of this timely and evocative collection, one can’t help but feel ever so slightly disheartened: Why, in the twenty-first century, are there still people in our global community who need to protest for the right to work, to vote, to love, to live?

Elie Wiesel once said, ‘We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented’. And so, we must continue to come together. For while none should ever need to petition for what most of us consider fundamental, by taking sides, by making our voices heard, perhaps we may inspire some hope for change, for a fairer future for all.

~

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour is a former inhabitant of Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Hong Kong and London. A graduate of Actors Centre Australia, she is currently a MA creative writing student at Chichester University. Her writing has appeared online at Wildness, Thresholds, Hong Kong Review of Books, and Graphite, and her essay, ‘Beyond the Barren Landscape: Elizabeth Harrower’s A Few Days in the Country’ was longlisted for Thresholds 2016 Feature Competition. Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.

Originally from Sydney, Nicole Mansour is a former inhabitant of Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Hong Kong and London. A graduate of Actors Centre Australia, she is currently a MA creative writing student at Chichester University. Her writing has appeared online at Wildness, Thresholds, Hong Kong Review of Books, and Graphite, and her essay, ‘Beyond the Barren Landscape: Elizabeth Harrower’s A Few Days in the Country’ was longlisted for Thresholds 2016 Feature Competition. Like Susan Sontag, she loves to read the way other people love to watch television.