('Montmartre' © Tien Anh, 2006)

*

A MAGICAL DISCOVERY OF MAGIC REALISM

by JANIS LANE

It all started in Montmartre.

After a fortuitous house swap to Paris, I was living my dream: a garden apartment in the 17th arrondissement, and immersed in the city with my young family for twelve whole days. From previous visits to Paris, I had many fond memories of the nearby district of Montmartre, with its creative Boho vibe, and it was there that I took my family first.

Having consulted our Paris with Children guidebook we set out on a child-friendly walk through Montmartre’s historic neighbourhoods, discovering along the way such hidden surprises as Le mur des je t’aime, the ‘I love you wall’ with its 311 declarations of love. My daughters were delighted. But the best was yet to come.

Further along our tour of Montmartre, after climbing a steep set of narrow steps, we arrived at Place Marcel Aymé. There, in a quiet corner, we came upon the square’s curious resident sculpture: that of a man caught halfway through the act of walking through a wall. The sculpture is of Aymé himself, and is inspired by his short story ‘Le Passe-Muraille’ (‘The Man Who Walked Through Walls’). It was fascinating, understated and bizarre, tucked away in a district so rich with culture and creativity, and I resolved to seek out the short story on my return to England.

Born in 1902 in Joigny, France, Marcel Aymé was the youngest of six children. His mother Emma, died when he was two, and his father, Joseph Aymé, sent him to live with Emma’s parents in the village of Villers-Robert, where he remained for eight years. Aymé then went to live with an Aunt in the small city of Dôle, where he completed his studies and served as a soldier in the French army.

Born in 1902 in Joigny, France, Marcel Aymé was the youngest of six children. His mother Emma, died when he was two, and his father, Joseph Aymé, sent him to live with Emma’s parents in the village of Villers-Robert, where he remained for eight years. Aymé then went to live with an Aunt in the small city of Dôle, where he completed his studies and served as a soldier in the French army.

After leaving the military, Aymé worked in a variety of trades before beginning his professional career in journalism. He finally settled on a path as a fiction writer and published his first book, Brûlebois, in 1926.

In 1932 he married Marie-Antoinette Arnaud, and within two years he experienced international success with his novel La Jument verte (The Green Mare). It was from that point that the world really took shape, in Aymé’s eyes.

The worlds Aymé creates are characterised by the familiar sights of town and country, where strange and unusual habitants exist alongside regular people who, in turn, often act absurdly. Storylines follow a straightforward narrative, but contain elements of the fantastic while also retaining a logical thread. Today, his work sits firmly beneath the banner of magic realism, though that term wasn’t coined until much later.

This juxtaposition of fantasy and reality lends itself to the short story form, and it’s for his short fiction that Aymé is best known. It is widely acknowledged that his short stories contain his best and most imaginative writing.

Settings and characters in Aymé’s works fall into two distinct categories: the real French countryside with its resident farmers, and urban Paris with its Montmartre proletariat. In keeping with the genesis of my discovery of the collection, I will focus on the title story, ‘The Man Who Walked Through Walls’.

The story is set in Montmartre and centres around the unassuming, and indeed ‘excellent gentleman’, Dutilleul, who, we are immediately informed, possesses a ‘singular gift of passing through walls without any trouble at all’.

I find myself drawn to Aymé’s pragmatic prose, in particular when describing the fantastic. Being a relative newcomer to magic realism (Alice in Wonderland being the main representative of prior forays), I can only assume this approach is characteristic of the genre. On further investigation I found this definition on Goodreads.com, to be the most succinct:

Magical realism is a fiction genre in which magical elements blend to create a realistic atmosphere that accesses a deeper understanding of reality. The story explains these magical elements as normal occurrences, presented in a straightforward manner that places the “real” and the “fantastic” in the same stream of thought.

Dutilleul initially shuns his ‘gift’, and seeks medical help to rid himself of his affliction. The doctor diagnoses ‘a helicoid hardening of the strangulatory wall in the thyroid gland’ and treatment is delivered with great economy of prose, a matter-of-factness despite the fantastic content, to comic effect:

He prescribed sustained over-exertion and a twice-yearly dose of one powdered tetravalent pirette pill, a mixture of rice flour and centaur hormones.

Dutilleul follows the procedure once, but any kind of exertion is unlikely in his role as a staid civil servant – we can assume much about his character from his ‘pince-nez with a chain’ and his black goatee – and he soon forgets about the treatment. The pills languish in a drawer.

A new boss looks unfavourably on Dutilleul and makes sweeping changes to procedure, which in turn makes the atmosphere inside the Ministry of Records where he works unbearable. Having been moved to a broom cupboard office and berated for his letter-writing skills, Dutilleul feels a sudden ‘a flash of inspiration.’

Stepping carefully into the wall, his head emerges on the other side, where he flashes a look of hatred at his boss. His head appears ‘mounted on the wall like a hunting trophy’, and he speaks to his antagoniser: ‘Sir … you are a ruffian, a boor and a scoundrel.’

Dutilleul continues to haunt his unfortunate boss, until ultimately ‘an ambulance came to collect him at home and took him to a mental asylum’.

Emboldened by his power, Dutilleul becomes an infamous and flamboyant jewel and bank thief. He dares the police to capture him – indeed, he allows them to capture him – only for them to later find him enjoying coffee on the outside, having walked through prison walls overnight.

Then, one day, he falls in love. The woman in question is spoken for and is jealously guarded in a house with many walls, partitions and locked rooms. These barriers pose no obstacle to Dutilleul, however, who strides through the walls to reach the lady, where ‘they made love until late into the night.’

The following morning, Dutilleul takes pills for a headache, and enjoys another night of marathon love-making. This point marks the beginning of the end for Dutilleul. On his way out the next day, Dutilleul experiences some physical resistance as he tries to step through those walls and partitions, behind which his lady love is secreted. And there he stops, realising with horror that the headaches pills he took were the prescribed pills from the doctor. Combined with his recent over-exertion, the treatment is finally working.

Aymé informs us that Dutilleul is still there, incorporated into the stonework of the wall, and that the moans of the wind on a quiet evening are in fact Dutilleul, lamenting the end of his illustrious career and the sorrow of lost love. But there is a small consolation for the ill-fated man. Dutilleul’s old friend and painter Gen Paul may at times take his guitar to console the prisoner with a song:

the notes of his guitar, rising from his swollen fingers, pierce to the heart of the wall like drops of moonlight.

It’s an ending tinged with melancholy, but one that follows the narrative thread to its most logical conclusion. That’s the essence of magic realism.

As The Man Who Walked Through Walls was first published in France in 1943, it’s easy to see that Aymé’s work was influenced by his own historic times. Other stories in the collection, such as ‘Tickets on Time’ where lives are rationed dependent on a person’s usefulness, and ‘The Wife Collector’ which sees a tax collector of integrity and compassion ultimately collecting wives in lieu of unpaid taxes, reflect the social trauma experienced by wartime France.

Aymé was a celebrated literary figure prior to World War II, but his reputation suffered after the liberation of France because of his outspoken criticism of left-wing France and his work on collaborationist newspapers. As a result, his writing was ignored for years. Today, however, critics consider Aymé’s stories to be among France’s greatest twentieth-century short fiction. As an introduction to magic realism, I feel lucky to have discovered ‘The Man Who Walked Through Walls’ and by extension, the other stories in the collection.

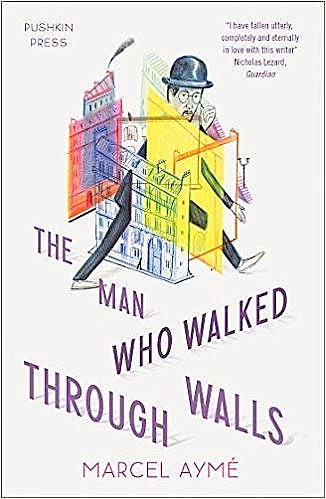

I was advised to read The Man Who Walked Through Walls in French to enjoy it to its fullest, but for those of us whose French falls short, I recommend the Pushkin Press edition with Sophie Lewis’s smooth translation. Either way, don’t miss out on the wisdom and fluid simplicity of these quiet gems. Like Nicholas Lezard, who wrote in his Guardian review of the collection, I too have fallen ‘utterly, completely and eternally in love with this writer’.

And the more I ponder it, the more I like to think that perhaps Marcel Aymé’s vivid imagination did see himself one day immortalised in stone. A stone wall.

~

Janis Lane has a Masters Degree in Creative Writing. Her flash fiction has appeared (or will) on the Flash Flood Journal, Ellipsis Zine and Pygmy Giant. She was longlisted for the 2016 Bath Short Story Award and is about to embark on a rewrite of her novel. She lives in Lyme Regis with her husband and three daughters, and can be found procrastinating in her stationery shop-cum writing haven, The Writing Room, which has wonky walls. She tweets @WritingRoomLyme.