('NYC - Chelsea Hotel' © nschouterden, 2013)

*

SEEN IN MIRRORS

by MIKE SMITH

*

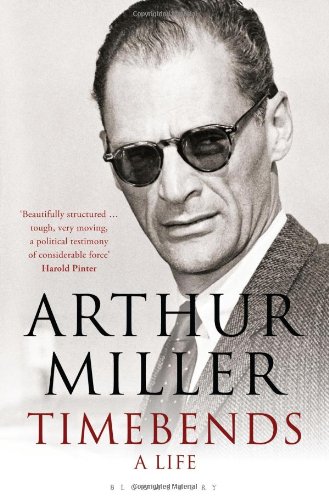

With the undoubtedly worthy, but essentially futile intention of researching Arthur Miller, whose stories ‘The Misfits’ and ‘Fitter’s Night’ I had been writing about, I bought myself a copy of his autobiography, Timebends.

I found it a hard read to begin with, but settled down reasonably well after a couple of dozen pages. Then, at the top of page 33, I hit his account of the last time he met the widow of his mother’s favourite brother, Stella. The story of this encounter – which took place when she was in her seventies, and he had just split from Marilyn Monroe and was living in the Chelsea Hotel – runs for three and a half pages in my paperback edition, perhaps something like 1,500-2,000 words, and reading it I got the distinct sense that I was reading a very good, well-structured and polished short story. In fact, I made a point of going back and finding the beginning, and marking the end, part-way through the final paragraph of that section.

It might seem to be a curious thing to do, but I have seen anthologies of short stories where sections have been lifted from larger works, usually novels. In fact, I’ve found the practice irritating, as if the editors have failed to find enough ‘proper’ short stories to fill their available space within whatever criteria they think they are working to. Yet here, in a non-fiction book, is a story beautifully told, with a clear beginning:

It might seem to be a curious thing to do, but I have seen anthologies of short stories where sections have been lifted from larger works, usually novels. In fact, I’ve found the practice irritating, as if the editors have failed to find enough ‘proper’ short stories to fill their available space within whatever criteria they think they are working to. Yet here, in a non-fiction book, is a story beautifully told, with a clear beginning:

Stella became a manicurist after Hymie’s death, and as a year passed and another with no sign that she wanted to marry again, my mother came to love her deeply, quite as though her noble loyalty were demonstrated.

The first clause alone would stand as a wonderful beginning to a short story, but the whole expands the back-story, and fills in some context. The ending is equally as powerful, bringing us round to the consequence, not merely of the encounter itself, but of the lifetime relationship between the writer and the woman in question. For him there is an epiphany that we, having been told the story, can share and understand, especially if we are trying to be writers too.

The narrator, having watched Stella leave, has stepped out onto the street, contemplating their meeting, and their family history.

I stood waiting for the light to change and saw quite simply that my style as a playwright had been influenced by Stella no less than by my mother, that somewhere down deep where the sources are was a rule never if possible to let an uncultivated, vulgarly candid, loving bleached-blonde woman walk out of one of my plays disappointed.

Those two sentences alone imply a worthwhile story lying between, but there is something else I can add, for in his introduction to I Don’t Need You Any More, reproduced by Bloomsbury in 2007 as the introduction to Presence, Collected Stories, there is the following nugget, of what Miller felt that a short story could, and perhaps should do: ‘…to hold them [events and character development] frozen and to see things isolated in stillness, which I think is the great strength of a good short story.’

This seems to me something like what Miller has done with the story of his last meeting with Stella. The middle of this faux tale is told as Miller sits in the barber’s chair, aware of, but not quite communicating with Stella, whose life and losses he reflects upon. The enormity of her loss, and the fact that she still battles on impresses him. That his unheralded arrival must have brought that loss into sharp focus is the beginning of his awareness of the significance that the meeting will come to hold for him. He senses that he will not see her alive again. Their conversation is fractured and incomplete, but the moment has been profound:

I could see her in the mirrors that faced each other along both walls, slipping out of her white coat, putting some finishing brush strokes to her thinning hair, for the ten thousandth time inspecting herself like a girl of eighteen with the whole world in front of her.

As all short story middles must, this one provides the context in which we will experience that closing epiphany quoted above.

And why wouldn’t a writer, or any teller of stories tell a true story, with any less skill and precision than he or she would tell a fictional one?

As I was coming close to finishing this essay I had a conversation with a retired teacher. When he was a schoolboy, he told me, he had seen no point in English lessons. After all, he spoke the language! So he used the time to do his maths homework, until, that is, the day that the teacher read them a short story. He began to describe the story to me: a dying man, and a friend who painted a leaf on a tree to try to keep his friend alive. Perhaps you recognise the story. He thought it might be one of Guy de Maupassant’s, but I recognised it as O. Henry’s ‘The Last Leaf’. “It made me,” my retired neighbour told me, “put down my pen and listen.” Isn’t that what short stories, always true one way or another, are meant to do?

~

Mike Smith writes short fiction as Brindley Hallam Dennis, and poetry, plays and essays as himself! He lives on the edge of England and blogs at www.Bhdandme.wordpress.com

One thought on “Seen in Mirrors”

Comments are closed.