('Hokitika' © David Frankel, 2008)

THE MAKETU ON MRS JONES AND ALL THAT

by KAREN WRIGGLESWORTH

~

So, when you’re from New Zealand and you grow up in the seventies and eighties, and especially when you attend an all-girls’ college, you have to study Katherine Mansfield for English. Right? Queen of the short story. Or so we were told.

At school, in tier-two English, we read Mansfield’s ‘The Doll’s House’ about that odd little girl called Kezia (whose name none of us could figure out how to pronounce) and the charming oily green door and the little glowing lamp. We probably read ‘The Garden Party’ too, and maybe even ‘Miss Brill’, but I don’t remember them.

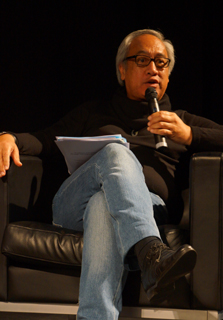

The best thing about taking tier-two English, for me at least, had nothing at all to do with Mansfield and her quaint and gossipy little colonial tales. It had, instead, to do with a writer no one, except for my wacky teacher, Miss Hart, seemed to know about: a Maori guy from the remote East Cape. A fella by the name of Witi Ihimaera.

I’m not a Maori myself. Let’s get that straight to start with. At least, not as far as I know, though my grandmother was close friends with a Maori princess, back in the twenties, when they went to nursing school together. Or so the story goes.

And so when I first heard about this Ihimaera fella, he didn’t pique my interest for his ethnicity. Or for the fact that he was a bloke: as far as I could tell, most authors were blokes. My growing-up years straddled the last dying stages of that peculiar ‘he’ default in everything then written by anyone about anything. It was so commonplace that we took no notice of it at all; this, despite my college years (the eighties) seeing my friends and I swamped by that feminist ‘Girls Can Do Anything’ slogan on stickers, billboards, and either written down or passed on orally at every opportunity.

And so when I first heard about this Ihimaera fella, he didn’t pique my interest for his ethnicity. Or for the fact that he was a bloke: as far as I could tell, most authors were blokes. My growing-up years straddled the last dying stages of that peculiar ‘he’ default in everything then written by anyone about anything. It was so commonplace that we took no notice of it at all; this, despite my college years (the eighties) seeing my friends and I swamped by that feminist ‘Girls Can Do Anything’ slogan on stickers, billboards, and either written down or passed on orally at every opportunity.

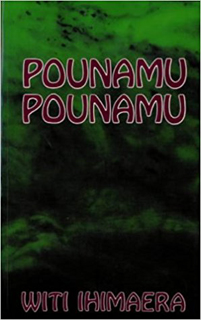

I never did find out why my teacher chose Pounamu, Pounamu for us to read. I guess it must have been snuck into the syllabus as an option by some progressive educational overseer, or more likely added for the Maori colleges that still dotted backwater towns, and that are now, for the most part, closed down.

But today, more than twenty years after we first had to read ‘The Maketu on Mrs Jones’, ‘A Game of Cards’ and ‘In Search of the Emerald City’, of all the set reading I was given by all of my different English teachers over the years, Pounamu, Pounamu is the only one I remember often and with warm emotion.

According to John MacAllister in his essay Writing Maori English: Voices in Pounamu, Pounamu, Ihimaera’s first collection of stories ‘received considerable publicity’ on publication in 1972:

…the first published volume of stories by a Maori writer, and achieved best-selling status in New Zealand, with annual reprints for a number of years following first publication […] In addition, Pounamu, Pounamu won third prize in the 1973 Wattie Book of the Year Awards.

It’s not easy to pinpoint exactly what it is about Ihimaera’s stories that gets under my skin so profoundly. Partly, I think, it has to do with him using language in a way that I’d not come across before. Familiar. Kiwi. It was unlike all other books I’d read up until that point in time, which had, for the most part, been either British (as in Enid Blyton or C. S. Lewis) or American (as in Carolyn Keene or Laura Ingalls Wilder). Sure, I’d read Maurice Gee’s Under the Mountain when the TV series came out. We all did – or at least my closest friends did, because they were geeky reader-types just like I was. But Gee’s book wasn’t ‘Kiwi’ by my definition, even though it was set here. But the voice of Gee’s book, not just its characters – Rachel, Theo and Mr Wilberforce – the authorial voice the book, the way it was told and its overall ambience, was a melding of here-and-there. Not fully ours. Not mine, at any rate, provincial girl that I was.

Ihimaera’s stories, however, were another thing altogether. I’d never come across anything like them. Never heard myself in print, if you will. Take ‘Beginning of the Tournament’, for example: ‘The phone rang for me while I was at work. It was Dad, ringing from Waituhi.’ This was how I spoke! How my friends spoke. It was just like immersing myself in a hot thermal bath at Rotorua, closing my eyes, and simply listening to the voices of the local people going about their day all around me. These are stories about an adolescent young Maori man fully within his world of family, mates, and cultural identity. A world so familiar it’s taken for granted, as is the specialness of his remote yet beautiful and haunting coastal home. It’s about sports and hard rural work and superstitions and uncles and aunties and cuzzies and bros. It’s about love and loss. It’s about life in this place, in this time; learning who we are, and learning to be who we are.

It was only many years later, as a twenty-something, that I discovered Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, and Jack Keroac’s On the Road. Although both were American and white, Hemingway and Keroac each use language in a similar way to Ihimaera in Pounamu, Pounamu: raw, unadorned, and directly to the point. No skirting about and adding fluff, no obfuscating. Just how things are. Plain spoken men, which as any writer worth his or her salt knows, is far easier said than done.

Pounamu, Pounamu (or Greenstone, Greenstone) is a collection of ten stories set amongst an extended Maori family on the East Coast of the North Island of New Zealand. The stories we studied at school included ‘A Game of Cards’, ‘Beginning of the Tournament’, and ‘Tangi’ – which translated as both ‘funeral’ and ‘weeping’. But the story that, even now, resonates most with me is ‘The Maketu on Mrs Jones’. Maketu is a real-world place, a small, mostly Maori settlement not too far from Tauranga in the Bay of Plenty. The word, separately, also means ‘a magic spell’. As Ihimaera puts it, ‘Maori believe that if a person gets a bit of you … he’ll be able to put a spell on you’.

Maori are traditionally a superstitious people, and even today such things as maketu, patupaiarehe, turehu and kehua (supernatural beings), although not so much outright believed in, are always considered and respected. Nowadays, powhiri (welcoming ceremony), karakia (a prayer or blessing) and tapu (sacred possessions, places or actions) are common experiences for many New Zealanders. They are a sign of respect, although no one really wants to mess any potential bad spirits about, even if you believe that there’s no such thing. It never does any harm to cover your bases, just to be on the safe side.

The story ‘The Maketu on Mrs Jones’ begins:

The story ‘The Maketu on Mrs Jones’ begins:

Here I am, sitting on the couch looking at my toenails, and suddenly I’ve remembered Mrs Jones. My wife has kicked me out of the bedroom until I’ve cut my toenails. I must admit that they are long – I haven’t cut them for over two months and they’re curling over the edge of my feet. It’s a shame to cut them though. If I grow them a bit longer, I’ll be able to swing on them. But I better cut them. My wife might give me a hiding […]

Mind you, it’s my own fault that I got caught out. If I hadn’t undressed so far away from the bed, she mightn’t have seen them. When her eyes grew wide with amazement, I’d thought it was a compliment. She’d backed away, a picture of typical feminine defencelessness and I’d advanced and […]

Get away from me with those claws! She’d screamed. Get away, get away!

I think it’s the familiar, self-deprecating Kiwi humour that I love most about this story.

I’ve recently discovered Ihimaera’s second, less well-known, short story collection, The New Net Goes Fishing. These are urban stories, telling what it was like for the people of Pounamu, Pounamu once they’d been displaced to the cities by the mass internal migrations of the seventies and eighties to find work. There is a welcome familiarity in these later stories, as well as a more confident voice reflecting the author’s greater experience in writing both what he knows and what he knows he wants to say. This second book of stories is good. Excellent, even. But, for me, they are somehow not quite in the same league as those in the Pounamu, Pounamu collection.

Ihimaera has written numerous books since his 1972 debut. His oeuvre includes several further collections of short stories, a large number of novels, and a semi-autobiographical work, Nights in the Garden of Spain. Some of his writing, such as The Whale Rider, has found its way onto the silver screen.

For my money, if you only read one book by a New Zealand author, you could do much worse than to make it Ihimaera’s Pounamu, Pounamu. And for all that, it was originally published nearly half a century ago, it’s still as relevant, and as reflective, of a certain slice of life in New Zealand as it ever was.

~

Karen Wrigglesworth is a New Zealand-based writer with a degree in mechanical engineering. Her nonfiction work has been published in New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom, and she also writes plays, short stories, and long-form fiction. Karen was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize for Flash Fiction in 2016.

Karen Wrigglesworth is a New Zealand-based writer with a degree in mechanical engineering. Her nonfiction work has been published in New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom, and she also writes plays, short stories, and long-form fiction. Karen was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize for Flash Fiction in 2016.