('Books’ © Jonas Tegnerud, 2010)

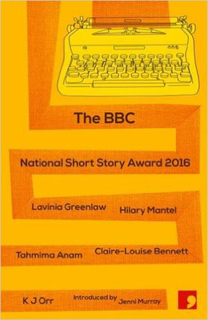

RUSHING THROUGH THE DARKNESS: THE BBC NATIONAL SHORT STORY AWARD

by DAVID FRANKEL

The BBC National Short Story Award is one of the most prestigious, and richest, short story competitions. Unsurprisingly, its anthologies, drawn from each year’s shortlist, continue to offer stories that encapsulate all the things that make contemporary short fiction so engaging and exciting. As with any competition anthology, the five stories included in this year’s satisfyingly pocket-sized collection are varied in tone and style but all reflect, in some way, the personal landscape of ordinary people.

The collection kicks off with Tahmima Anam’s ‘Garments’, the story of Jesmin, a worker in an Indian sweatshop. When the story begins she is ‘six shirts behind’ and trying to catch up when her friend, Mala, asks Jesmin to become her fiancé’s second wife, and to help her find him a third. Jesmin agrees; the man, Dalal, is considered a catch because he works in an air-conditioned shop. The women inhabit a world of terrible working conditions, brutal strikes and poverty, but this backdrop is tempered by their friendship and their ability to find humour where they can. However, marriage is the only way they can see to find a decent place to live and avoid the sexual harassment of the foreman: ‘If you’re a girl you have many problems, but all of them can be fixed if you have a husband.’ In any case, Jesmin is very practical in her expectations of marriage:

If they have to divide the sex, that’s fine with her, and if he wants something, like he wants his rice the way his mother makes it, maybe one of them will know how to do it.

But, even with such low expectations, her experience of marriage is grim. Dalal turns out to be violent, ugly, dirty and uncaring. He is also impotent. It transpires that Mala has paid Dalal to marry her, and her two friends are both a sweetener in the deal and an attempt to cure his impotency.

Anam avoids sentimentalising her characters or their plight. The writing is punchy and direct and she gives the story additional power by the artful feeding in of Jesmin’s backstory; her seduction and abandonment by a man she had thought would marry her, and her subsequent punishment and exile from her village.

‘Morning, Noon and Night’ by Claire-Louise Bennett is, perhaps, the most enigmatic of the stories in the collection. Rather than a clearly defined narrative, Bennett presents us with a collage of incidents and memories that paint a vivid portrait of its central character. The story is an internal monologue of a woman obsessed with detail. As she recounts recent events in her life, her story is intercut with manic observations of her surroundings and the minutia of her life.

‘Morning, Noon and Night’ by Claire-Louise Bennett is, perhaps, the most enigmatic of the stories in the collection. Rather than a clearly defined narrative, Bennett presents us with a collage of incidents and memories that paint a vivid portrait of its central character. The story is an internal monologue of a woman obsessed with detail. As she recounts recent events in her life, her story is intercut with manic observations of her surroundings and the minutia of her life.

Bennett builds a wonderful impression of a character locked into a shrinking world of self-reflection. The shape of the story is slow to reveal itself, but it is worth the wait: the first four pages are a beautiful discourse on breakfast ingredients – fastidious, obsessive, but poetic.

Pears should be small and organised nose to tail in a bowl of their very own and perhaps very occasionally introduced to a stem of the freshest red-currants, which ought not to be hoisted like a mantle across the freckled belly of the topmost pear, but strewn a little further down so that some of the scarlet berries loll and bask between the slowly shifting gaps.

There is also a darker streak to many of her thoughts. Amongst the beautiful ephemera with which she has filled the empty spaces of her life, sudden moments of brutal rage burst through her polite fussiness. She recalls a neighbourhood cat killing a wren that has been visiting her garden:

I was so upset I wanted to take that cat to a hot pan and scar its foul backside in an explosion of hot oil. I’ll make you hiss you little shit.

And, in her inner world, people often fair no better.

The narrator reveals how, in looking for a place to skulk, she had asked people in the neighbourhood about a secluded piece of land, claiming an interest in horticulture. She soon realises that her ‘sly enquiries’ are ‘listened to rather too attentively’ and she is obliged to follow through, planting a vegetable garden.

As her interest in gardening grows, we follow her memories through an ‘ill-starred liaison’ with a man, and the slipping away of her career until, alone with her thoughts, she spends her time chopping the vegetables she has grown and dissecting the events of her life. She could be talking about either when she says,

Chopping, taking it all to pieces, in a kind of contracted stupor, morning noon and night; trying not to pay any heed to my reflection in the mirror as I do so.

We can tell from the title of Lavinia Greenlaw’s ‘The Darkest Place in England’ that we aren’t going to get a happy story. Sure enough, what the author delivers is a bleak but immediately engaging coming-of-age narrative.

Young Jamie works in her father’s shop in a small rural community. She is naïve and filled with self-doubt. The story begins when Jamie is given a bunch of flowers by a customer. The gift is a thoughtless act — the man is merely trying to get rid of them — but they set in motion a chain of events. The flowers draw the attention of Piper, the local bad girl, who takes Jamie for a night out in a speeding car full of older boys. In the nightclubs of the nearby town the flowers continue to be a catalyst for the evening’s events, culminating in a drunken brawl between the inexperienced Jamie and some other girls.

What could have been a clichéd story of a boozy night gone wrong and its consequences is a genuinely moving and poignant story told in bursts of vivid description and dialogue. The central narrative is enhanced by sudden changes in view point where we see Jamie through the eyes of other characters, most notably the man with the flowers who, by coincidence, is also the one to rescue her at the end of the night when she is left alone and semi-conscious in a city street.

Someone else stops. He has passed other girls lying in the street but this one is different. She’s holding a bunch of flowers. It’s the girl from the café lying in the street at two in the morning. What has he done? He thinks she must be here because he gave her the flowers — which is true, she is.

He drives her home but the story doesn’t end there. Jamie is left disappointed with a feeling that she is ‘still waiting for something to happen.’ Drunken trips to the city become a regular thing:

She does it again and again for the rush through the dark and the press of boys and the push of the music and the rise and fall within herself.

Finally, ignored by anyone who might have helped her, she passes out in a frozen field, narrowly avoiding death by hypothermia.

While she is recovering, the people she knew and who witnessed her drunken progress deny all knowledge of her decline and fall. The only person who seems to have been touched by her presence is the man who gave her the flowers. Sometime later, he comes back to see her only to be ignored as she is reading text messages from a friend. Whether accidentally or not, the story’s characters are careless of each other; they are all footnotes in each other’s lives, disinterested and remote.

In Hilary Mantel’s ‘In a Right State’ a group of down and outs seek shelter and company in the waiting room of an Accident and Emergency Unit. The narrator has been evicted from her home, and carries all of her belongings in two bags: ‘You’ve seen these bags. They’re very nearly un-bags, faint-striped as though they’ve been through a car wash.’

She shares her evening in the waiting room with the other ‘regulars’, all of whom suffer with strange or imagined conditions of one kind or another, joking and fighting alternately. The humour they use to deal with their situation is ever present. The rapid-fire sarcasm of their banter provides the backdrop to the string of mini-crisis that make up their evening. ‘Somebody has filled in the quick crossword, got half way through and then — what? Died? “Quick, but not quick enough!” I say.’

Like Mantel’s characters, the genuinely funny commentary masks a deeply sad narrative underlying the story. The narrator’s rambling internal monologue and eccentric bursts of conversation paint a vivid portrait of her broken mental state. She is fascinated by celebrity interviews in the well-thumbed magazines of the waiting rooms she inhabits, and she returns repeatedly to the questions in them, imagining herself being interviewed, or asking the questions to the others.

The quizzes never ask you what you’d save if you were evicted. They ask, what would your superpower be? I say, getting my furniture back off those conniving bastards.

The jibes and the little fragments of memory that leak into her monologue reveal glimpses of the life she once had: home, car, partner and job. We wonder what happened to her and, as dawn breaks and she heads back out into the world, we sense that she does too.

From the chaos of Mantel’s waiting room, we are whisked off to the quiet restraint of early morning in a genteel district of Buenos Aires. K J Orr’s ‘Disappearances’ is a touching account of a fledgling friendship between a retired plastic surgeon and a waitress, but there is darkness below the surface of this carefully crafted, multi-layered story.

The surgeon narrator of the piece seems to be floundering in his retirement, which has left him feeling ‘nervous and shifty’. Despite his assurance that he is ‘not to be pitied’ we sense his loneliness, or at least his aimlessness. We soon discover that through Argentina’s political troubles the narrator has managed to thrive no matter who was in charge: ‘While the leadership had wives and mistresses, I was in demand.’

Although it’s clear he hasn’t been an active part in any regime, he has been complicit – profiting in it and taking advantage of it. There are hints that he feels guilt and we feel that he is seeking change or hiding from something: ‘No one I know is about. I do not look as I usually would. I do not speak as I usually do.’

Wrapped up in his own world, he goes into a café which, although local, he has never noticed before, where he strikes up a tentative friendship with the waitress, Beatriz. As well as being from the opposite end of the social spectrum, it soon becomes apparent that she and her family fared worse under the past regime. Her father ‘disappeared’ and her brother’s life had to be saved by a surgeon. Our narrator observes that her hands are scarred by lacerations. ‘Of course,’ he notes, ‘not everyone has had my easy run through the years.’

Both surgeon and waitress seem lonely and although the emotion in the story is restrained, we sense a developing intimacy between them. This promise is short-lived though. Their relationship is based on a lie. He has led Beatriz to believe that he is the kind of surgeon who saved her brother rather than the kind who dined with the leaders who allowed her father to be taken away. This is compounded when he pretends not to know a rich customer who is abusive to his new friend. In reality the woman is a friend and client.

When his lies are exposed, ending the possibilities that were unfolding, Orr delivers the blow with precision and restraint, noting only that, as Beatriz walks away, he watches ‘her shoulders become small, like those of a child.’

The embarrassment he feels at being caught in his lie is quickly replaced by the cold detachment of the surgeon’s eye, and authority, as he instructs us to ‘Pay attention. This is important’. He then delivers a detailed analysis of Beatriz’s physical appearance, ending with her scarred hands. His dispassionate tone is belied by the detail of his observations. As with the rest of the story, the beauty and power of the ending is in the things which are not spoken, but which we feel none the less.

The stories collected here avoid extravagance or gimmicks. Each is powerfully written, vividly evoking the life of the protagonist. If anything unites the stories it is that each presents us with a character with a crystal clear voice that carries us briefly but completely into their world.

~