('Foxes at Night' © Jarkko Järvinen, 2015)

*

OUR EPIC JOURNEY FROM NOTHING TO NOWHERE

by JENNIFER HARVEY

~

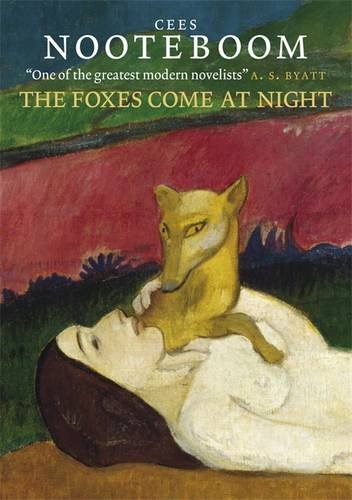

The Foxes Come At Night. What an elusive title. So obscure and opaque, its meaning more intuited than understood.

The words themselves come towards the end of this collection by Cees Nooteboom, in the story ‘Paula II’. They are spoken by Paula, which is fitting, because Paula is dead, and the conversation she is ‘remembering’ alludes to an ancient belief that foxes were messengers of the gods, intermediaries between the souls of the living and the dead.

The foxes come at night and, like Paula, this is when we hear them talk; this is how we communicate with the dead. It’s not an idea we are prone to dwell upon these days – that the dead are there for us even after they are long gone. In our modern world, we seem to have no need for foxes, for intermediaries. For us, the dead are silent.

But it poses a dilemma, this modern-day determination to push death to the outer limits of our awareness, because in a world without myth, without ritual, without intermediaries and interlocutors, a world where death has no dominion, how then do we face it? How do we react to it? How do we accept it?

For Nooteboom, the answer is clear. The answer is literature.

Death is at the heart of this collection; it is the central idea upon which Nooteboom – as in so much of his writing – meditates. But it’s a philosophical focus that can put him at odds with some readers, and writers. When J. M. Coetzee reviewed Nooteboom in the New York Review of Books, he rather pointedly noted:

This […] is Nooteboom’s peculiar misfortune as writer: that he is too intelligent, too sophisticated, too cool, to be able to commit himself to the grand illusioneering of realism, yet too little anguished by this fate – this expulsion from the imaginative world of the heartfelt – to work it up into a tragedy of its own.

I find this criticism too harsh. Uncommitted to the heartfelt, really? I would argue that in The Foxes Come At Night Nooteboom has crafted deeply humane stories that are only strengthened by the intelligent and sophisticated understanding he brings to the subject matter.

Central to this understanding is Nooteboom’s contemplation of what death is: paradoxically, something that is experienced by those who are left behind.

In our epic journey from nothing to nowhere we leave behind an endless trail of garments. I feel a pang of nostalgia for certain items sometimes, which is all the more reason not to dwell in old photographs.

~ taken from ‘Heinz’

No one ever wants to imagine that their life, or for that matter their death, will seem insignificant when viewed from the vantage point of a future they will not experience. But what if all that can be known of us after death really can exist only in the miscellaneous bits and pieces we leave behind?

These objects, to other people, are simply ‘things’, imbued with no significance. No one can ever fully understand the meaning of the possessions we once treasured, or why a particular photograph is important, because without our memories, they possess no meaning. And so, this is exactly the moment a writer must step up to the mark and begin to contemplate the unthinkable and express such things despite their difficulty – exactly what Nooteboom does.

These objects, to other people, are simply ‘things’, imbued with no significance. No one can ever fully understand the meaning of the possessions we once treasured, or why a particular photograph is important, because without our memories, they possess no meaning. And so, this is exactly the moment a writer must step up to the mark and begin to contemplate the unthinkable and express such things despite their difficulty – exactly what Nooteboom does.

The narrator in ‘Heinz’ finds it is better not to contemplate old photographs: the emotional hazards they contain can be too great. The story begins with a thought experiment: the narrator is looking at an old photograph and pretending not to know the people in the shot. He wants to see the scene dispassionately, objectively. But he tries in vain because the sight of an old tartan scarf he is wearing in the photograph sets in motion a whole surge of memories, because the scarf possess meaning for him. And so the narrator’s abstract attempt at objectivity only serves to highlight the time which has passed since the photo was taken; lives have been lived and come to an end, and it proves impossible to forget who these people are.

It is only when we understand that the narrator himself is in the photograph that we understand what he is trying to do – to look at the photo as an outsider would, both now and in the future. He is trying to imagine someone else looking at him, after he is long gone, and imagining a life for him, a story. ‘In fifty years’ time … the people in it will have been relegated to the realm of the dead … by which time, observing the image will have become a melancholy exercise, fleeting and inconsequential.’ What starts as an abstract experiment suddenly becomes unexpectedly poignant. Look at a photograph of yourself, Nooteboom suggests, and see how close it can bring you to understanding and feeling how fleeting life is.

In the hands of a less ‘intelligent’, ‘sophisticated’, ‘cool’ thinker, such ideas could become very maudlin and insipid, but it is precisely Nooteboom’s ability to delve deep into an abstract idea that lifts his writing to such a satisfying emotional level. The treacherous scarf in the photograph becomes the jumping off point for the story of Heinz, a flamboyant and melancholy figure whose life the narrator can now tell us about – because Heinz, his friend, is gone, his story is complete, his end is known.

We can follow the narrator’s friend Heinz on his epic journey from nothing to nowhere, and understand the significance of the apparently insignificant – the long lost scarf, the innocuous photograph – and in this way we come a little closer to understanding who it is that is gone, what it is that has been lost. We can even come closer to understanding what it may feel like for those left behind after we ourselves are gone.

This is the wonderful thing about Nooteboom’s writing: such big, incomprehensible ideas can be distilled into such small, intimate details, like the scarf – ‘green with a small tartan pattern’ – or even the photograph itself. It is in these details that he helps us to wrestle with the abstract and the intellectual. Nooteboom understands that it is via the intimate, familiar and often overlooked details that we come to accept both life and death.

There is a moment in the story ‘Last Afternoon’ when the narrator realises she is becoming used to the absence of her former lover. The story itself opens very abruptly, brutally even: ‘And then suddenly he was dead.’

Such a dispassionate statement almost makes you recoil, unsure whether to read on. But the story that unfolds is surprisingly calm and contemplative.

Sitting in her garden, the narrator watches the shadow of a cypress tree move across the garden wall as the sun sets, a moment in which she recalls her dead lover.

The quiet scene is at odds with the sudden fact of her lover’s death but as she sits there she becomes aware that his death is actually a slower process than it may at first appear.

…just as she had fifteen minutes ago when the shadow of the cypress tree reached the stone wall, she felt certain: the man she had lived with for years, and who had died a few summers back, was now truly dead. He had taken his time, she thought to herself […] they had already been miles apart when he was alive, but that […] did not mean he was dead to her when he died […] it was only now at this mysterious moment of the cypress’s shadow creeping up against the garden wall that he was dead to her […] the present, long-drawn out moment of beginning to forget him, of his passing into a shadow of himself, his real death.

It’s a strange idea this, that death can be a far longer process for the survivors than for the dead themselves, but again Nooteboom shows us that the way our memories unfold, and fade, and resurface over the years means the dead are forgotten and remembered in a constant cycle, and if we are to accept someone’s absence in our lives we must constantly accept and learn to understand the many ways loss manifests itself.

It’s a strange idea this, that death can be a far longer process for the survivors than for the dead themselves, but again Nooteboom shows us that the way our memories unfold, and fade, and resurface over the years means the dead are forgotten and remembered in a constant cycle, and if we are to accept someone’s absence in our lives we must constantly accept and learn to understand the many ways loss manifests itself.

This idea is considered most fully in the two linked stories, ‘Paula I’ and ‘Paula II’. In these stories, the living narrator, prompted once again into remembering by a photograph, talks to the now dead Paula about the people they once knew and the lives that have been lived since she died.

“…what is it about remembering the dead? Yes, I know, I won’t get an answer to that, nor to the question I really want to ask, which is, How is it that the older you get the more your life begins to look like an invention? Hard to say which is worse, getting old or being dead, but then you have never been old and I have never been dead.”

~ from ‘Paula I’

Paula herself joins in the conversation in the second half and tries to express something about death and being. She is the fox that comes at night, the bridge across the unfathomable chasm between life and death.

“That last brief moment […] I could still see […] I had never given my hair much thought. It must have been the most ephemeral part of me, I suppose. I saw it more vividly than ever before, and I was suddenly overtaken by such a love of myself, as if I had never got round to paying heed to the person I was. I had missed myself, all those years, I only found myself at the very last. What I remember is a feeling of insane love. Can you imagine? Suddenly I realized who had died […] my hair […] it was shiny, silken. I wanted to stoke it.”

~ from ‘Paula II’

There is a fearful poignancy in both stories, which comes from the understanding the two protagonists share, namely that it is only by remembering someone that we can keep them ‘alive’. But the memories in these two stories differ slightly from the others in the collection. It’s almost as if every previous story has been building up to this point.

In ‘Paula I’ we can witness the increasing clarity about death, which has been developing through the collection, when the narrator vividly recalls the sound of Paula’s voice and her memorable laugh: ‘I can hear you now’ he says ‘…that voice we will all remember to the end of our days.’

It’s a comment that is given added weight because of what has come before, in ‘Heinz’, when the narrator asks if anyone can remember the voice of Heinz’ dead wife Arielle.

She was utterly gone, so much so that it was as if she’d never been there. When I asked what her voice had been like he clammed up […] Voice, voice? How should I know after all this time?

And yet it is only through such an intimate memory that we can ever hope to catch a hold of the dead, keep them with us a little longer and make sure they do not disappear so ‘utterly’.

Paula herself acknowledges as much when she explains:

I am my memories […] but how long I can hold on to them remains to be seen. Only when they are all gone will I be truly dead, that is what I meant when I said: I am still alive. I have died but there is life in me yet […] You are the only one who has really called me. The others thought of me from time to time, but none of them could find me. Their grief, if that is what it was, lacked energy, the distance was too great.

In the end, there is no greater tragedy of course. Dying is something we must all face, it is the ultimate ‘grand illusioneering of realism’. But I would argue that it is only by thinking about it, in all its many facets, emotionally and intellectually, that we can hope to face this reality peacefully and to accept it.

What Cees Nooteboom shows us in The Foxes Come At Night is that this is in fact possible. The trick is to look closely at life itself and, when the time comes, to remember what we can, and to rejoice in the remembering, not as some grand illusion but as something wondrous and imaginative, nostalgic and melancholy and, above all, ‘heartfelt’.

~

Jennifer Harvey is a Scottish writer now based in Amsterdam. Her work has appeared in Carve Magazine, Litro Online, The Guardian and various anthologies. She has been shortlisted twice for the Bridport Prize and her radio dramas have won prizes and commendations from the BBC World Service.

Jennifer Harvey is a Scottish writer now based in Amsterdam. Her work has appeared in Carve Magazine, Litro Online, The Guardian and various anthologies. She has been shortlisted twice for the Bridport Prize and her radio dramas have won prizes and commendations from the BBC World Service.

~

Image of Nooteboom © Simone Sassen