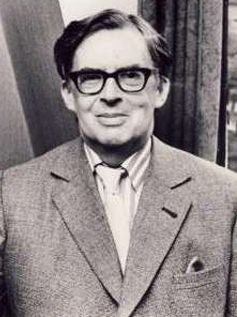

(Image © Oriol Martí, 2008)

A COLD HAND: THE STORIES OF ROBERT AICKMAN

by FRANCES GAPPER

Even when it’s fairly clear what’s mainly happened in a Robert Aickman story, the text still puzzles and disturbs with unanswered questions and loose ends. Aickman withholds rationales and rationalisation, sparking our interest and curiosity. He’s a master of the odd and compelling moment, the tiny riddle.

In his Guardian column ‘A Brief Survey of the Short Story’, Chris Power wrote that Aickman ‘dispenses almost entirely with the scaffold of exposition’. Dreadfulness is withheld, deflected, and we rarely get the ending we might have been expecting. Indeed, “Never explain: never apologise” was one of Aickman’s favourite phrases, according to his personal secretary, Barbara Balch.

As well as writing fifty or so ‘strange’ (his name for them) stories over thirty years from the late 1940s, Aickman edited eight of the Fontana ghost story anthologies. His own story collections include Dark Entries, Cold Hand in Mine and Tales of Love and Death.

He was born in London, England, in 1914, the grandson of Richard Marsh, author of occult novel The Beetle. Abandoned by his mother and raised by a father he later described as the oddest man he’d ever known, he had a lonely childhood. As an adult he had pasty skin and bad teeth, was polite, good company and charming, or rude and unpleasant, according to Jenny Chandler, wife of horror writer Ramsey Campbell. She added that he sometimes took irrational dislikes, but was sensitive and good at reading human signals.

Aickman was married to Edith Ray Gregorson, a literary agent and writer of children’s books, until, following a spiritual experience and fed up with his infidelity, she left for an Anglican convent in Oxfordshire and became a nun. He had a brief affair with the beautiful Elizabeth Jane Howard; together they wrote a collection of ghost stories, We Are For the Dark. Howard later described Aickman, in an interview with Tartarus Press, as ‘very manipulative, and very keen on power’, vastly egotistical and not that good a writer. But ‘a very good literary critic’.

Aickman thought the ghost story akin to poetry in its compression and intensity, and his work has been described as ‘English Eerie’ and ‘English Kafka’. In 1946, he co-founded the Inland Waterways Association, its aim being to restore Britain’s canal system, which was then in a state of dereliction. His interest in canals seems oddly fitting: the experience of reading his work is like taking a solitary walk along a canal path – the litter and tangled undergrowth, the danger, the absence of any escape route. People disappear into canals…

Aickman thought the ghost story akin to poetry in its compression and intensity, and his work has been described as ‘English Eerie’ and ‘English Kafka’. In 1946, he co-founded the Inland Waterways Association, its aim being to restore Britain’s canal system, which was then in a state of dereliction. His interest in canals seems oddly fitting: the experience of reading his work is like taking a solitary walk along a canal path – the litter and tangled undergrowth, the danger, the absence of any escape route. People disappear into canals…

That Aickman was shockingly good at lesbian subtext can be seen in several of his stories, for instance, ‘Bind Your Hair’. This fabulous story, which appears in Dark Entries, describes a visit paid by recently engaged couple Clarinda Hartley and Dudley Carstairs to his parents’ house in Northamptonshire. Clarinda is much approved of by her prospective in-laws, but she starts to feel depressed.

As she lay in bed watching wisps of late-autumn fog drift and swirl past her window, she felt that inside the house was a warm and cosy emptiness in which she was about to be lost. She saw herself, her real self, for ever suspended in blackness, howling in the lonely dark, miserable and unheard; while her other, outer self, went smiling through an endless purposeless routine of love for and compliance with a family…

Will Clarinda choose wildness and the out-there (real self) or conformity (false self) – or resolve her dilemma in some other way? The extraordinary Mrs Pagani, arriving uninvited at a drinks party hosted by the Carstairs family and stirring up an electrically sexualised atmosphere – especially between herself, Clarinda, and Dudley’s sister, Elizabeth – offers a veiled challenge.

By now Mrs Carstairs had brought Mrs Pagani a drink. “Here’s to the future,” said Mrs Pagani, looking into Clarinda’s eyes, and as soon as Mrs Carstairs had turned away, drained the glass.

“Thank you,” said Clarinda.

“Do sit down,” said Mrs Pagani, as if the house were hers.

“Thank you,” said Clarinda, falling in with the illusion.

Unfortunately, the second half of the story – bats, a spooky child, Satanist rituals, orgies – is a bit disappointing by comparison. But first Aickman’s Sapphic sleight of hand powers another intriguing scene, or rather non-scene. Dudley knocks on the door of his sister’s bedroom, where ‘Elizabeth had got out a quantity of clothes and ranged them round the room for inspection and comparison by Clarinda…’ Before allowing him in, we’re told Elizabeth ‘drew on a sweater’. Why does Elizabeth need to cover herself, since if anyone’s been undressing in order to try on clothes it would surely be Clarinda, not her? Plenty is ‘in the air’ here, nothing shown or stated.

How does Aickman draw the reader into a story? It’s not the situation that secures our attention, or at least not immediately. It’s the voice and the bits of stimulating information, the resonant words. In ‘The School Friend’, the main character is, from the start, linked with the ancient Classical world and magical knowledge:

Sally combined a true love for the Classics, the ancient ones, with an insight into mathematics, which, to the small degree that I was interested, seemed to me almost magical.

She also has commercial savoir-faire: while still a student, she publishes ‘a little book of popular mathematics which, I understood, made her a surprising sum of money’. Fairy-tale tropes add to the engaging mix. Sally ‘not only could remember nothing of her mother, but had never come across any trace or record of her’. An intellectual Cinderella, ‘…when Sally was not scrubbing the floor or washing up, she was studying Vergil and Euclid…’ By this point in the narrative (not far down the second paragraph) the story has exerted its own magical power, compelling us to read on.

‘The Hospice’ is one of Aickman’s most surreally dream-like and Kafkaesque tales, set in a building that seems to be a cross between a hotel or boarding house and a care home or mental hospital – or perhaps something else entirely? Maybury, the protagonist, seeks shelter here after getting lost and attacked by an animal, perhaps a cat. In the hospice’s overheated dining room, huge amounts of food are pressed upon him by a waitress (or nanny/nurse) who, at first, won’t take no for an answer, then has a tantrum when he positively declines. He ends up having to share a bedroom (also far too hot) with Bannard, who’s given to making unsavoury sexual remarks and is possibly a vampire, more certainly (it’s implied) a murderer. The curtains are drawn, but there’s no window behind them. After one unsuccessful escape attempt, foiled by lack of petrol and a weird memory lapse, next morning Maybury accepts a lift in a hearse to the nearest bus stop.

‘The Hospice’ is one of Aickman’s most surreally dream-like and Kafkaesque tales, set in a building that seems to be a cross between a hotel or boarding house and a care home or mental hospital – or perhaps something else entirely? Maybury, the protagonist, seeks shelter here after getting lost and attacked by an animal, perhaps a cat. In the hospice’s overheated dining room, huge amounts of food are pressed upon him by a waitress (or nanny/nurse) who, at first, won’t take no for an answer, then has a tantrum when he positively declines. He ends up having to share a bedroom (also far too hot) with Bannard, who’s given to making unsavoury sexual remarks and is possibly a vampire, more certainly (it’s implied) a murderer. The curtains are drawn, but there’s no window behind them. After one unsuccessful escape attempt, foiled by lack of petrol and a weird memory lapse, next morning Maybury accepts a lift in a hearse to the nearest bus stop.

The story is drenched in Maybury’s anxiety and physical discomfort. Although terrified the bite on his leg will spread poison through his system and disable him, making it impossible for him to continue working, for some reason he never asks for first aid, or even washes the wound. Meanwhile his normalising efforts themselves betray fear and disturbance. ‘He concentrated on the thought that nothing had actually happened that was dangerous’, recollecting that in his life so far he had encountered ‘…many things strange to him, most of which had proved in the end to be apparently quite harmless.’ Here, it is the qualifiers – ‘most of which’ and ‘apparently’ – that disturb.

The whole story is nightmarish, but an actual nightmare featuring Maybury’s wife provides an especially scary moment:

… for there was Angela in her nightdress with her hands on her poor head, crying out “Wake up! Wake up! Wake up!’’ Maybury could not but comply.

Has he dreamed of Angela, or did the real Angela somehow break through into his dream? (And why ‘poor head’?)

There’s no doubting Aickman’s influence on weird fiction. Neil Gaiman has said that reading him is like watching a magician work:

Yes, the key vanished, but I don’t know if he was holding a key in the hand to begin with. I find myself admiring everything he does from an auctorial standpoint. And I love it as a reader. He will bring on atmosphere. He will construct these perfect, dark, doomed little stories…

Aickman’s persistent undermining of ‘ontological security’ and destabilisation of experience is very Freudian, as Jeremy Dyson pointed out in his radio broadcast ‘The Unsettled Dust: The Strange Stories of Robert Aickman’. While Nina Allan, writing in Starburst magazine, argued that Aickman started the psychological trend in horror literature and that his stories are the missing link between the Victorian ghost story – e.g. M.R. James – and modern horror. However, Aickman himself resisted Freudian insights and the (what he considered mistaken) belief – adopted at the time of the Industrial and French Revolutions – that everything could be known. ‘Spirit is indefinable, as everything else is indefinable…’ Perhaps he’s not so much post-Freud as pre-18th century?

~

Frances Gapper’s third story collection, In the Wild Wood, will be published in 2017 by Cultured Llama Press. Her other collections are The Tiny Key (Sylph Editions, 2009) and Absent Kisses (Diva Books, 2002). She is a senior editor at The Forge lit mag.

Frances Gapper’s third story collection, In the Wild Wood, will be published in 2017 by Cultured Llama Press. Her other collections are The Tiny Key (Sylph Editions, 2009) and Absent Kisses (Diva Books, 2002). She is a senior editor at The Forge lit mag.

One thought on “A Cold Hand: The Stories Of Robert Aickman”

Comments are closed.