(‘The Dystopian Dance Floor #2’ © Wouter Walmink, 2006) *

DEFINING THE BALLARDIAN

by KATE KRAKE

*

Only a handful of authors are granted eponymous adjectives – those words that come to represent what a particular writer writes and anything else that shares those same qualities. We tremble at the draconian control of the Orwellian. We muse over the strange nightmares of the Kafkaesque. Some among us might even risk the dark, unknowable madness of the Lovecraftian. But what of the Ballardian?

Ballardian: of the English writer, James Graham Ballard – celebrated science fiction visionary, prolific short story writer, novelist and socio-cultural commentator.

The Ballardian takes on the soul of modern life. It’s a soul ever advancing, perhaps reluctantly, into a dystopian future; a landscape thwarted and then moulded by human interference. The Ballardian is the mind, churning behind the eyes, watching this future unfold. Sometimes those eyes are closed and the world moves on in a dreamscape.

The Ballardian captures our contemporary condition. It is violence, terror and war. It is the often-ambiguous beauty expressed in our entire experience of love, sex and death. It’s gross celebrity culture. It’s crass political campaigning. It’s modern conveniences and ancient paranoid threats. The Ballardian is this whole universe of circumstance, so acutely recognisable and shown for all horror and absurdity in our day-to-day existence. It’s the life we’re living, or the one we’re watching others live out on the screens we’ve all got permanently in front of our eyes in our own, very Ballardian, information-overloaded existence.

So who was this Ballard, and how did he get his name listed as a canonical English adjective that stands for so very much?

So who was this Ballard, and how did he get his name listed as a canonical English adjective that stands for so very much?

J.G. Ballard was born in 1930 in the Shanghai International Settlement and died in 2009. The son of a textile chemist, he was an English boy growing up in the textile industry in Shanghai, who ended up living out the final years of World War II in a Japanese internment camp. These experiences formed the basis of Ballard’s novel Empire of the Sun, published in 1984, which was adapted into a multi-award-winning film of the same name, in 1987. As renowned as this novel and film came to be, Empire of the Sun is often considered a side step from what we typically consider a Ballardian work to be. Though perhaps it was this early experience of the diaspora and then imprisonment that positioned Ballard firmly on the outer edges of literature, in both thematic and more practical terms, throughout his writing career.

While a celebrated novelist, Ballard’s short fiction is the mainstay of his appeal as a science fiction writer. Reading his shorts, we see huge ideas condensed to their very essence by the short story form. After all, that is the beauty of the medium and an appeal Ballard himself was keenly aware of. ‘Short stories have always been important to me,’ he wrote in the Author’s Introduction to The Complete Short Stories of JG Ballard. ‘I like their snapshot quality, their ability to focus intensely on a single subject.’

Many novelists dabble with the short form, but for Ballard, short fiction was an immutable and constant foundation, even when he ventured into longer works – which, he admitted in that same introduction, almost all started life as short stories. As a young man, his first award and publication came for a short story called ‘The Violent Noon’, which he wrote while he was studying medicine in Kings’ College, Cambridge. The piece was published in the university paper, Varsity. This was the turning point for the young Ballard, who then abandoned his plans of becoming a psychiatrist and decided instead to study literature.

After an early exit from his university career, he continued writing short fiction, though it was some time before his next publication. He worked in various jobs, including a pilot in the Royal Air Force, and it was at this time, while stationed in Canada, that he turned his hand to writing genre fiction – after discovering the market of American science fiction magazines.

After an early exit from his university career, he continued writing short fiction, though it was some time before his next publication. He worked in various jobs, including a pilot in the Royal Air Force, and it was at this time, while stationed in Canada, that he turned his hand to writing genre fiction – after discovering the market of American science fiction magazines.

In December 1956, Ballard had his first professional short story publications: ‘Escapement’ in New Worlds, and ‘Prima Belladonna’ in Science Fantasy. Following these career-defining publications, he continued writing science fiction, forging his own unique paths through the genre with his short stories and novels, as well as his critical pieces.

Ballard was, and still is, quite unique in his short fiction publications, writing numerous collections of short stories that were linked together as novels. These ‘condensed novels’, as he called them, can be read as stand-alone pieces but are all the more powerful when read in their collected context.

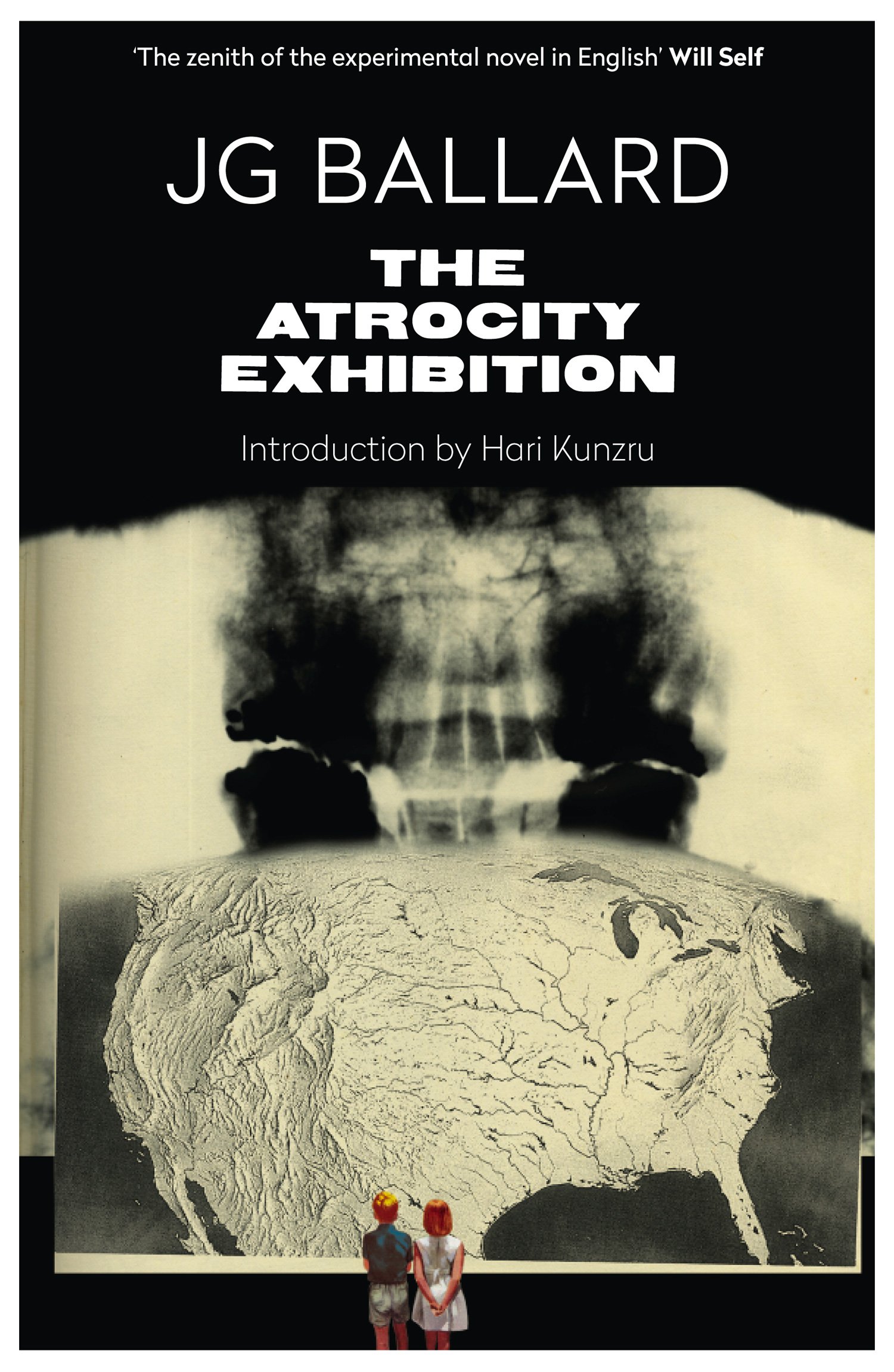

The Atrocity Exhibition, the most renowned of these collections, was published in 1970 and was comprised of fifteen short chapters, all of which had been previously published as separate pieces in various publications. With its preoccupations with mass media and psychosis, a blurring of internal and external landscapes, and a future vision of World War III, the collection was a bold experiment with both the short story and the novel as a story telling form.

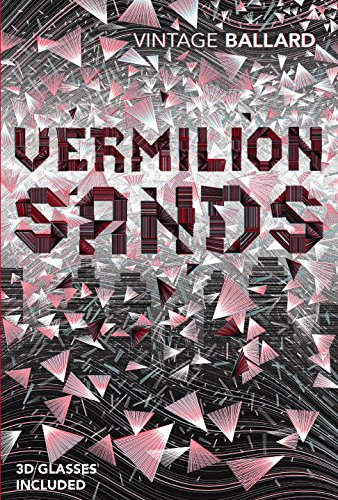

The following year, Ballard published Vermilion Sands, another linked collection, which includes ‘Prima Belladonna’. Vermilion Sands takes us to a beachside artist colony and, through a series of pieces all set in the same locale, looks at artistic expression as it meets technological advancement. Our characters are superficial and lonely, existentially warped and tired. In Ballard’s own words prefacing the book:

Vermillion Sands has more than its full share of dreams and illusions, fears and fantasies, but the frame for them is less confining. I like to think, too, that it celebrates the neglected virtues of the glossy, lurid and bizarre.

Throughout his career, Ballard was praised as much as he was criticised. His early work saw him shunned by the science fiction community, who regarded his style as too avant-garde, too psychological, not at all scientific and therefore ineligible to belong to the sci-fi genre. Ballard shunned them right back. For him, science-fiction culture from the mid-twentieth century was a fantasy that ignored the very real dangers of technological advancement. It was too caught up in a blind optimism that regarded all science as good science; a stark contrast with the actual world, which was living the dark effects of the H-Bomb and Auschwitz, a world in which people were deeply sceptical and even scared of science. For Ballard, the inner space – the meeting point between interior mind and outside reality – was the most important playground for science fiction, the place where these fears of modern advancement could be explored.

From this outsider position, he became a beacon of the science-fiction New Wave, a sci-fi sub-genre that grew out of writers rejecting the action-adventure simplicity of earlier sci-fi culture, in favour of more literary, experimental writing. But even as a part of the New Wave, Ballard walked the line between science fiction and literary fiction, hovering on the edges of both. Just as he was rejected for being too literary for science fiction, he was not taken seriously as a literary writer, due to his genre work. He did receive literary recognition with the Man Booker-nominated Empire of the Sun, but denied the prestige that accompanied it by turning down an OBE and refusing invitation to join the Royal Society of Literature.

Yet despite all of this (what might be considered) categorisation anxiety, Ballard is now retrospectively considered ‘Great’ as both a science-fiction and a literary writer, and any poor reception he met with throughout his long career has now been overshadowed by overwhelming esteem and praise.

His legacy is diverse, his influence extending into, seemingly, all realms of popular culture. Obviously, an author with such a career will influence multiple generations of writers, and countless writers have and will continue to name J.G. Ballard as a significant inspiration. The genre-bending speculative fiction of China Miéville owes a clear debt to Ballardian ideas. English novelist Will Self, while not generally regarded as a science-fiction writer, confirms Ballard as a fundamental influence and mentor. In our contemporary literary landscape, where genres are allowed, and even sometimes are expected, to be slippery, where science fiction doesn’t need to have anything scientific about it, the sci-fi genre as a whole owes a debt to this prolific author. We have writers now happily walking both worlds of highbrow literary esteem and genre fiction: Margaret Atwood would spring to mind for many readers, though she famously rejects science fiction as a genre label, preferring to call her work ‘speculative’ instead.

His legacy is diverse, his influence extending into, seemingly, all realms of popular culture. Obviously, an author with such a career will influence multiple generations of writers, and countless writers have and will continue to name J.G. Ballard as a significant inspiration. The genre-bending speculative fiction of China Miéville owes a clear debt to Ballardian ideas. English novelist Will Self, while not generally regarded as a science-fiction writer, confirms Ballard as a fundamental influence and mentor. In our contemporary literary landscape, where genres are allowed, and even sometimes are expected, to be slippery, where science fiction doesn’t need to have anything scientific about it, the sci-fi genre as a whole owes a debt to this prolific author. We have writers now happily walking both worlds of highbrow literary esteem and genre fiction: Margaret Atwood would spring to mind for many readers, though she famously rejects science fiction as a genre label, preferring to call her work ‘speculative’ instead.

It’s not only writers who have been touched by the Ballardian. He has had a profound influence on film, television and visual arts. I’ll even go so far as to argue that musical acts as artistically and chronologically diverse as David Bowie, Joy Division, Madonna, The Buggles, The Sisters of Mercy, Radiohead, Gary Numan and The Klaxons, to name a few, all reference Ballard’s works in their music. His own creativity was drawn from multiple spheres of influence – cinema, particularly New World cinema and the French New Wave – surrealist art and Pop Art, theatre, science, psychology, cultural theory, and, of course, literature. Perhaps this is why his vision extends so fluidly and inspires through all mediums of creativity. Perhaps, also, it’s the universal nature of the vision itself.

Ballard continues to be celebrated as one of those prophetic writers with an eerie ability to predict the future. He claimed no visionary sensibilities; he was just writing stories set in futures he estimated by examining the world’s existing patterns. Ballard’s magic power was observation, not divination. And the Ballardian vision was of a timeless future, of a fundamental truth of the human condition.

~

Kate Krake writes speculative fiction, non-fiction and occasionally dabbles in other fiction genres. Kate blogs about popular culture, health, wellness and also writes about creative writing at www.thewriteturn.com. She lives in Brisbane, Australia with her husband, daughter and two beagles. Find out more on www.katekrake.com.

Kate Krake writes speculative fiction, non-fiction and occasionally dabbles in other fiction genres. Kate blogs about popular culture, health, wellness and also writes about creative writing at www.thewriteturn.com. She lives in Brisbane, Australia with her husband, daughter and two beagles. Find out more on www.katekrake.com.

One thought on “Defining the Ballardian”

Comments are closed.