('MacRitchie Reservoir Sunset ' © Ravenblack7575 , 2014)

BACK TO THE RESERVOIR

by NICOLA DALY

*

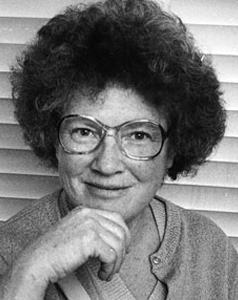

I discovered Janet Frame in 1997 quite by accident. I was writing a thesis on Sylvia Path when I stumbled across her. At the time I remember an Australian I worked alongside telling me that back home in Perth they studied this remarkable New Zealander until she was coming out of their ears. He spoke fondly of getting to grips with her novels in college and then, later, when he was travelling, reading her short stories on long haul flights. His original description of her work might have put me off picking up one of her books because he described her stories as ‘delightful’. No, twenty-year-old graduate wants to read books that are charming, nice or delightful. However, I did venture further than the rather callow book jacket, and from the first I was intrigued by this writer. Her immense personal courage, which becomes apparent to the reader when they read her biographical notes, wasn’t all that attracted me, it was also obvious that Frame possessed a rare gift: she was able to tell a tale spanning some years in a clear and concise way. Frame also had the ability to take the mundane events of life and transform them into something quite extraordinary. In many ways, Frame did for the domestic hum drum what Tracey Emin did for the unmade bed.

Frame was born in Dunedin and brought up in Oamaru on the east coast of South Island. She did not come from a family of academics, in fact her family were very poor. Through hard work and encouragement from her parents, Frame and her siblings managed to study, and she became a teacher, though she left the profession within a year due to illness. As her early short stories show, she was deeply affected by the drowning of two of her sisters in separate accidents in 1937. Ten years later Frame had her first nervous breakdown and spent time in psychiatric hospitals until 1955. Mental illness and the experiences she endured are recurrent themes in her work.

In 1951, Frame was awarded the Hubert Church Memorial Award for her first book of short stories. She was in the Seacliff Asylum at the time and receiving the prize resulted in the cancellation of her scheduled lobotomy. It later turned out that Frame had suffered not from Schizophrenia as diagnosed, but anxiety and depression — a result of years of family trauma triggered by her siblings’ deaths.

Frank Sargeson, a New Zealand writer who befriended and mentored Frame when she left Seacliff Hospital, pointed out from the beginning that Frame’s stories were very similar to those of Dylan Thomas, by which I think he meant that her early short stories relied a good deal on autobiographical subjects. Family, friends, and tragic and comic domestic episodes are something to which most readers can relate.

Frank Sargeson, a New Zealand writer who befriended and mentored Frame when she left Seacliff Hospital, pointed out from the beginning that Frame’s stories were very similar to those of Dylan Thomas, by which I think he meant that her early short stories relied a good deal on autobiographical subjects. Family, friends, and tragic and comic domestic episodes are something to which most readers can relate.

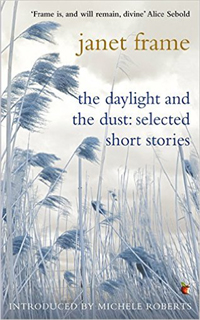

The Daylight and the Dust: Selected Short Stories comprises a cross section of Frame’s work, taking the reader from small-town life to inner-city London. Many of the stories in this collection are preoccupied by accounts of her early life in New Zealand. One such story is ‘The Reservoir’. It recounts how, in the summer holidays, Frame and her siblings used to tire of their tiny world that ended at a reservoir. The story takes place during a year when there is a drought and the school holidays are stretched even longer because they are unable to open the school without water. Frame explains how, for a long time, the children obey their parents and do not go further than the reservoir, and then how, inevitably, once boredom sets in, the children venture further afield. She uses humour when describing the exhausting journey to the reservoir: ‘Well are we going to the Reservoir or not? That was someone trying to sound bossy like our father.’

Frame and her friends get lost, and there are injuries and arguments along the way that make the scenes all the more vivid to the reader. However, they press on determined to prove their parents wrong about the reservoir, because at this point they don’t understand why the adults fear the water so vehemently: ‘How we wished it was our little Creek.’ But this changes when the children arrive and darkness begins to fall rapidly.

Lost in the dark and having to sleep on the banks of the river, they suddenly fear the eels that adults have told them come out of the water, and the dead sheep along the banking that they know can cause infantile paralysis. ‘No one would know where we were, to bring us an iron lung with its own special key.’ It is these thoughts that send the siblings racing home to their parents. Once safely back at home, the children display all the confidence of youth once again when their father cautions them about the reservoir. ‘We said nothing. How out-of-date they were! They were actually afraid!’

Frame is not merely preoccupied with autobiographical stories from her childhood and her troubled early adulthood spent in the hospitals; some of her stories are speculative, others are concerned with her observations of people. A thread running through all the stories is loneliness and isolation, and the difficulty many outsiders have forming relationships. Although these stories were written decades ago, these themes are still relevant. Like all the stories in this collection they offered the reader a sense of what it is to be human. The voice Frame adopts in many of the tales is also critical to her success as a short prose writer. She is never patronising, or clever for the sake of being clever. She never makes the reader feel small or insignificant. In fact, she relays the tale to the reader just the way one might tell a friend.

Frame’s varied terrain moves from old-fashioned storytelling, to speculative fiction, to observational nuggets such as ‘The Teacup’. This story centres around three lonely, middle-aged characters – Bill, Edith and Jean – who live in the same building. The events  centre around a special teacup Edith buys for Bill when she persuades him to rent the free room in the building she lives in. The cup itself is really a symbol of the hopes Edith harbours for a relationship with Bill once he moves into the tenement: ‘On Bill’s first night she could not disguise her happiness.’

centre around a special teacup Edith buys for Bill when she persuades him to rent the free room in the building she lives in. The cup itself is really a symbol of the hopes Edith harbours for a relationship with Bill once he moves into the tenement: ‘On Bill’s first night she could not disguise her happiness.’

Frame adeptly builds up the pace of the story, telling how Edith slavishly works to make Bill comfortable within his new lodgings in an attempt to become part of his life. However, it soon becomes apparent that Bill is not interested in a romantic relationship with her.

We see Frame’s awareness of human nature in the conversations Edith and Jean have about Bill. It’s fairly obvious that whilst Jean is envious of Edith’s seemingly warm friendship with Bill, she has no intention of admitting it. This is made worse by Edith’s constant prattle about Bill’s likes and dislikes. The situation reaches boiling point when Bill’s special teacup goes missing. Frame carefully employs gentle humour in order to deal with the situation — while the incident itself seems petty to Bill, Edith is frantic: ‘Edith’s voice had a note of desperation, as if the incident had brought her suddenly to the limit of her endurance.’

Frame perfectly depicts the minuscule world that Edith and Jean inhabit inside the tenement. She creates an environment fully of petty accusations and one-upmanship. ‘She had her suspicions of Jean. She looked once more around Jean’s room, as if trying to uncover the hiding place.’

Bill remains a hazy character throughout this particular story. Most of what the reader learns about him is through Edith. ‘He was secretive, he didn’t understand, he had been in the Army.’

Frame writes in a such a way that the reader feels Edith’s disappointment when she returns from a weekend at her sister’s to discover that Bill has left their lodgings without leaving her so much as a note. By this point in the story, we have learnt that this for Edith is just one disappointment in a life of so many:

She spoke longingly as if emigrating to Australia were another of the good things that was denied her on the last minute, as if it was somehow concerned with the affair of Bill and the lost teacup and never walking arm in arm, in the park, in summer.

In ‘The Teacup’, the reader is made aware how something of seemingly no significance – like a missing piece of crockery – can have far-reaching consequences for all involved. The missing cup is used to create tension between the women and expose all Jean and Edith’s insecurities and flaws, as we see in the wonderful scene at the close of the story where Edith spots Jean in the green grocer’s, buying herself a mountain of food that she later pretends a friend bought her:

“Oh,” Jean replied, “I had a friend to visit me.”

“A friend? A man?”

“Yes. A man.”

“I didn’t see him.”

It is not easy to surmise why these stories shine. They are uncomplicated and well-paced. Frame engages her audience by peppering the stories with both tragedy and humour, and by using real characters and events to which the reader can relate. There is a naïve beauty to her stories about family life, personal experiences and childhood that make her work charming. And through these stories, she transports the reader to the orchards and paddocks of New Zealand where she grew up.

~

Nicola Daly has had prose, poetry and non-fiction worked published widely. She has appeared in magazines such as The Rialto and Myslexia. In 2014, she won the gatehouse literary prize for her novella entitled And the Years Rolled by at an Alarming Rate.