photo © Romain Guy, 2012

by Charlotte Osborn

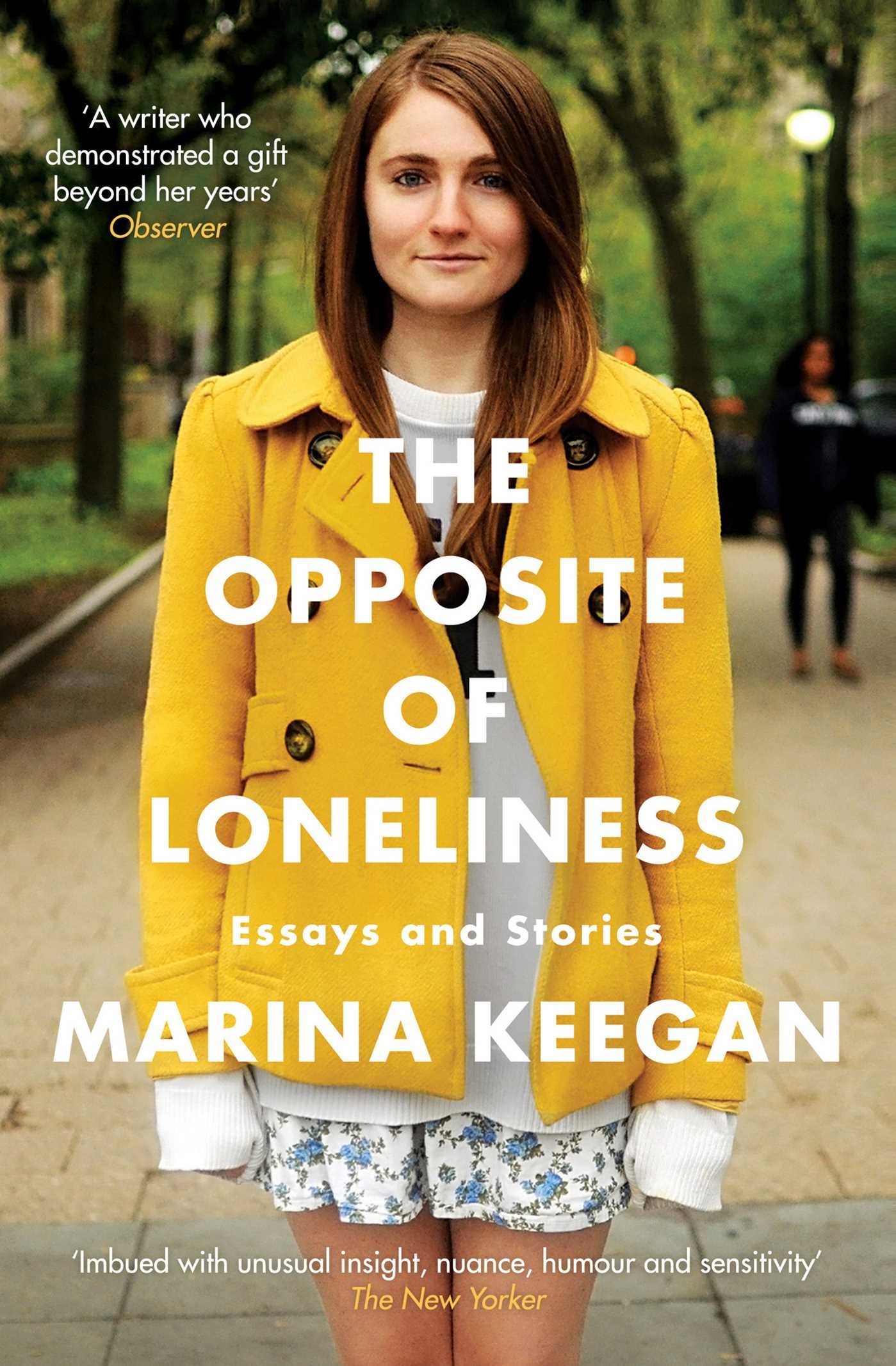

If you have ever wanted to experience the agony of humanity through fiction, you need to read Marina Keegan’s ‘Cold Pastoral’. Taken from a collection of compassionate stories in The Opposite of Loneliness, ‘Cold Pastoral’ is a story about the distorted perception of love, the impact of loss left on the living, and the curse of impenetrable jealousy.

Keegan graduated magna cum laude from Yale in May 2012, already set for success with a vast collection of short stories and essays written during her time at university. Tragically, five days after her graduation, Keegan was killed in a car crash on the way to her father’s birthday in Cape Cod, at only twenty-two-years-old. The Opposite of Loneliness is an affecting collection of Keegan’s writing, published posthumously and put together with help from professor, mentor and friend, Anne Fadiman. ‘Cold Pastoral’ is one in particular of Keegan’s stories that demonstrates her discernible talent, and a literary style already cultivated at such a young age.

The story opens with the unnamed narrator introducing her passionate relationship with her boyfriend, Brian, as being at the stage ‘where we couldn’t make serious eye contact for fear of implying we were too invested’. The relationship is then left in an indefinite status as Brian dies from an aneurism before the first page ends.

The whole story hinges on the main character’s internal struggle of needing to categorise the significance of her relationship: did she really love this boy and, therefore, should she feel more pain than she does, or should she have ended it when she was ‘hooking up with people I was 80 percent into’ and move on with her life?

The informal tone of the first person narration creates a sense of inclusion between narrator and reader, as if the main character is divulging details of her private life to a trusted friend. There is an edge of unapologetic honesty, where the narrator ‘thought about ending things’, reflecting the kind of transparent conversation that could occur between close friends. There is no pretence here, and, as a reader, you get a sense of a real person with genuine thoughts and feelings opening up to you. In this way, Keegan makes you care about the relationship that has already passed, and also empathise with the main character, all in half a page, tearing your heart out before you even learn the characters’ names.

This agony is construed and continued through a series of episodes which force the main character to suffer sadness, self-pity, jealousy, anger, anxiety and hatred, before finally surrendering to a melancholic realisation at the close of the story. Needless to say, that is a lot of emotion to experience in twenty-two pages of prose, and the reader is not let off the rollercoaster of these sensations at any point, but all for good reason.

After the shock of the first page, Keegen effectively keeps the reader engaged by drawing back to the couple’s attitude toward their relationship: ‘we took a certain pride in our ambiguity’. It is hard, however, to decipher clearly whether or not the narrator is looking back through rose-tinted glasses of nostalgia, muddled further by a startling admission: ‘Alive, his biggest flaw was most likely that he liked me. Dead, his perfections were clearer.’ Introduce the  concept of Brian’s previous ex-girlfriend Lauren Cleaver and you find yourself tangled in a web of blurred perception. How can the narrator move on from a relationship she hardly knows how to classify, while competing for the right to mourn against a significant ex-lover?

concept of Brian’s previous ex-girlfriend Lauren Cleaver and you find yourself tangled in a web of blurred perception. How can the narrator move on from a relationship she hardly knows how to classify, while competing for the right to mourn against a significant ex-lover?

Keegan is skilled in depicting such real pain and confusion that may be endured in real-life situations, as with the scene of Brian’s funeral: Lauren enters the room, her face ‘swollen and red and she was breathing in staccato bursts’. Her anguished appearance is witnessed by everyone in the room, but for the narrator, a neurotic instability kicks in: the fact that she thinks Lauren looks ‘thin and beautiful’ and that moment provokes a wild realisation that ‘of course I wasn’t the girlfriend’. The narrator’s anguish ignites:

I can’t explain how or why, but it filled me with a profound, seething anger … followed, inevitably, by waves of familiar self-disgust.

These twists of pain and confusion pepper the narrative, appearing unexpectedly, just as emotions overwhelm us in times of real grief.

Keegan also breaks many so-called ‘rules’ of short story writing. She doesn’t provide a name for the main character, nor do we get a sense of her physical appearance. The narration concentrates, instead, on the feelings and observations of the protagonist, including her memories of a romanticised past, and her anxieties towards an unknown future. The writing is raw and honest. Whilst some could argue that this style comes because the story was technically unfinished, in terms of publication – The Opposite of Loneliness was published posthumously from Keegan’s notes and manuscripts – for me, Keegan’s writing is effective, providing an intimate connection to the human condition.

It is impossible, however, to disregard the skill of Keegan’s writing in capturing the moments of human nature that we are most frightened to acknowledge. The honesty of the story exposes the faults in human existence; allowing jealousy to surpass rationality is a big theme in this story. The narrator becomes consumed with comparing herself to Lauren, the ex-girlfriend, and allows this obsession to breed contempt and malice, instead of nurturing sympathy and understanding for a suffering human companion. It takes a long time for the narrator to think about Lauren ‘without also thinking about myself’. Courage is needed for a person to admit that they have been at fault, and I think the reader takes the same journey as the narrator – learning that she is not the virtuous human she has strived to be, and that being imperfect is actually okay.

‘Cold Pastoral’ is an unrefined, yet candid story of love, loss and jealousy. For a writer considering the craft, Keegan demonstrates that you don’t have to adhere to all the conventional ‘rules’ to create an engrossing short story. For the reader looking for an engaging read, the story provides a glimpse at the ways in which challenging circumstances can affect a person’s outlook on life in an intense and sensitive narrative.

~

Charlotte Osborn studied English and Creative Writing BA (hons) at the University of Chichester. Now based in London, she enjoys writing a variety of short fiction, essays and articles, and has been published in the Sunday Mirror’s Travel section. She was shortlisted for the Worthing WOW Festival 2016 Children’s Short Story Competition with A Loony Landing.

Charlotte Osborn studied English and Creative Writing BA (hons) at the University of Chichester. Now based in London, she enjoys writing a variety of short fiction, essays and articles, and has been published in the Sunday Mirror’s Travel section. She was shortlisted for the Worthing WOW Festival 2016 Children’s Short Story Competition with A Loony Landing.